Have you ever wondered why 132 characters is such a common width for printers? Many printers produced lines of 132 characters, such as the groundbreaking Centronics 101 dot-matrix printer (1970), the ubiquitous DECwriter II terminal (1975), the Epson MX-80 dot-matrix printer (1981), and the Apple Daisy Wheel Printer (1983). Even CRT terminals such as the DEC VT100 (1978) supported 132 columns. But why the popularity of 132 columns?1

After researching this question, I've concluded that there are two answers. The first answer is that there isn't anything special about 132 columns. In particular, early printers used an astoundingly large variety of line widths including 50, 55, 60, 70, 73, 80, 88, 89, 92, 100, 118, 120, 128, 130, 136, 140, 144, 150 and 160 characters.2 This shows there was no strong technical or business reason to use 132 columns. Instead, 132 columns became a de facto standard due to the popularity of the IBM 1401 computer and its high-performance 1403 line printer, which happened to print 132 columns.

The second, more interesting, answer is that a variety of factors in the history of data processing, some dating back a century, led to standardization on several sizes for printed forms. One of these sizes became standard line printer paper holding 132 columns.

The IBM 1401 computer and the 1403 printer

The first printer to use 132 columns appears to be the IBM 1403 line printer, which provided output for the IBM 1401 business computer. The IBM 1401 was the most popular computer of the early 1960s, largely due to its low price. Earlier computers had been limited to large corporations due to their high cost; the IBM 705 business computer rented for $43,000 a month (almost $400,000 in current dollars). But the IBM 1401 could be rented for $2500 per month, opening up the market to medium-sized businesses that used it for payroll, inventory, accounting and many other business tasks. As a result, over 10,000 IBM 1401 computers were in use by the mid-1960s.

The IBM 1403 printer was an important part of the 1401's success. This high-speed line printer could print 600 lines per minute of high-quality text, said to be the best print quality until laser printers.10 "Even today, [the 1403 printer] remains the standard of quality for high-speed impact printing," at least according to IBM. By the late 1960s, half of the world's continuous forms were printed on IBM 1403 printers.3

Because the IBM 1403 printer was so popular, its 132-column format became a de facto standard, supported by later printers and terminals for backward compatibility. The 14 7/8"×11" green-bar paper that it used4 remains popular to this day, available at office supply stores.5

Accounting machines / tabulators

Now I'll discuss the history that led up to 132 columns on 14 7/8" paper. The key actor in this story is the electric accounting machine or tabulator. While these machines are mostly forgotten now, they were the cornerstone of business data processing in the pre-computer era (history). Tabulators date back to the 1890 census when Herman Hollerith invented these machines to tabulate (i.e. count)6 data stored on punch cards. Later tabulators used relays and electromechanical counters to sum up values, were "programmed" for different tasks by a plugboard of wires, and could process 150 punch cards per minute.

By 1943, tabulators were popular with businesses and governments; IBM had about 10,000 tabulators in service. These machines were complex, able to handle conditionals while adding or subtracting three levels of subtotals and formatting their alphanumeric output. Accounting machines were used for a wide variety of business data processing tasks such as accounting, inventory, billing, issuing checks, printing shipping labels or even printing W-2 tax forms. While these machines were designed for businesses, tabulators were also pressed into service for scientific computation in the 1930s and 1940s, most famously for nuclear bomb simulations during the Manhattan Project.

IBM 285 accounting machine (1933)

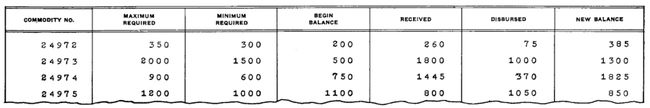

The earliest tabulators displayed the results on mechanical counters so an operator had to write down the results after each subtotal (details). The development of the tabulator printing unit in the 1920s eliminated this inconvenient manual step. One popular printing tabulator was the IBM 285, introduced in 1933. This machine printed values using 3 to 7 "print banks", where each bank consisted of 10 numeric type bars.7 The output below shows 7 column-output, generated by a 285 tabulator with 7 print banks.

The character spacing was 5/32" (a value that will be important later), yielding columns 1 7/8" wide. This spacing was about 50% wider than standard typewriter spacing (10 characters per inch) even though the tabulator used standard typewriter line spacing (6 lines per inch). As you can see from the output above, this caused large gaps between the characters. So why did the accounting machine use a character spacing of 5/32"? To understand that, we have to go back a decade.

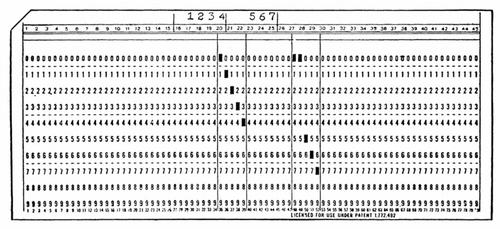

Early IBM punch cards had 45 columns with round holes spaced 5/32" apart.8 The image below shows one of these cards. Each column contained one hole, representing a digit from 0 to 9. One machine used with punch cards was the "interpreter". It read a card and printed the card's contents at the top of the card above the holes. The interpreter used a 45-column print mechanism with type bars spaced 5/32" apart to match the holes.

In 1928, IBM introduced the "modern" punch card, which held 80 columns of data (below). These cards used rectangular holes so the holes could be closer together (0.087" spacing). However, IBM kept many of the mechanisms designed for 45-column cards, along with their 5/32" spacing. The result was mismatched products like the IBM 550 Interpreter (1930) that read an 80-column punch card and printed 45 characters at the top of the card. As a result, the characters didn't line up with the holes, as you can see below.9 Likewise, The 285 accounting machine used a type bar printer with 5/32" spacing, even though it used 80-column cards.

IBM 405 (1934) and 402 (1948) accounting machines

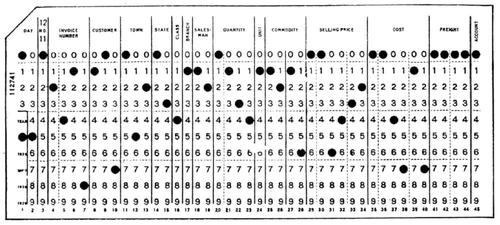

The IBM 285 tabulator could only print digits, but in 1934, IBM introduced the 405, a tabulator that could print alphanumeric information, followed by the improved 402 accounting machine in 1948. Alphanumeric output greatly expanded the uses of the tabulator, as it could print invoices, address labels, employee records, or other forms that required alphanumeric data. The IBM 405 had 88 type bars that moved vertically to print a line of output (below).18 Note the gap for a ribbon guide between the two blocks of type bars.

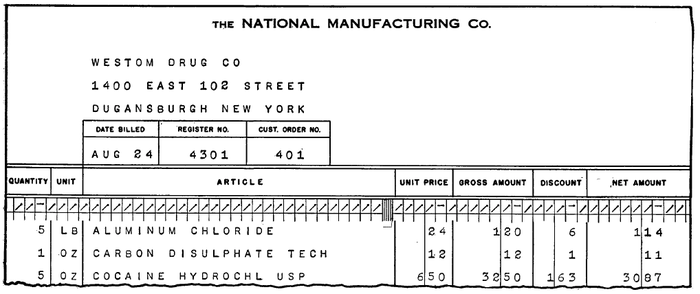

The figure below shows sample output from a 405 tabulator, showing alphanumeric characters on the left side. As with the earlier tabulators, the 5/32" character width resulted in widely separated characters. Note that the headers and boxes were not printed by the tabulator, but were pre-printed on the form.

At first forms were hand-fed sheets of paper, but for convenience these were soon replaced by continuous-feed forms.12 To keep forms from slipping out of alignment, holes were added along the sides so forms could be fed by pin-feed or tractor-feed mechanisms. These forms often used a removable 1/2" perforated strip on each side containing the feed holes.22 Thus, the hole-to-hole width was 1/2" less than the overall width, and the printable region was 1" less than the overall width.

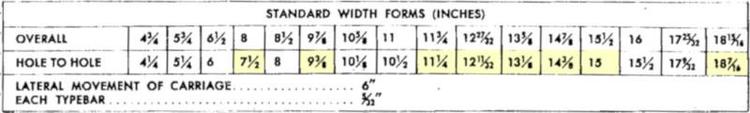

Businesses would order customized forms for their particular needs, but these forms were usually produced in standardized widths, given below.11 Surprisingly, these arbitrary-seeming form sizes are still standard sizes available today. Many of the standard form widths are round numbers such as 8" and 11", but there are also strange numbers such as 12 27/32" and 18 15/16".13 I explain most of these sizes in the footnotes.1516 Note that most of the unusual widths are multiples of the 5/32" character width (hole-to-hole); I've highlighted these in yellow. I believe making the width a multiple of 5/32" was a deliberate choice.14

The 402's 88 character output fit exactly onto a 14 7/8" wide form, while also being a multiple of 5/32" (hole-to-hole).17 I believe that this was the reason that 14 7/8" paper became a standard. This width is the dimension of standard green-bar line printer paper still used today, so this dimension is very important. Note that this paper size became a standard before commercial computers even existed.

IBM 407 accounting machine (1949)

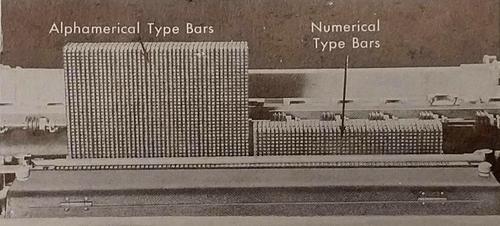

The successor to the IBM 402 accounting machine was the IBM 407 accounting machine, introduced in 1949. The most important feature from our perspective was the move from type bars to type wheels. Each type wheel had 47 characters (letters, numbers and symbols) around the circumference and rotated at high speed to print the correct character.19 The tabulator used 120 of these wheels to print a line of 120 characters.

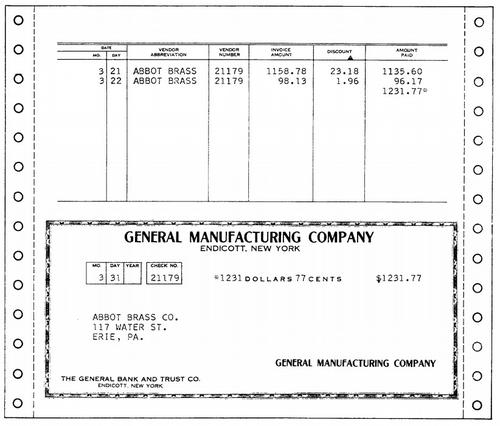

The narrow type wheels enabled the 407 to print 10 characters per inch (standard typewriter pica pitch). The output below shows how the tabulator could issue checks using pre-printed forms. Note that the 407's output looks like normal typing compared to the widely spaced characters of the earlier 405 and 402.

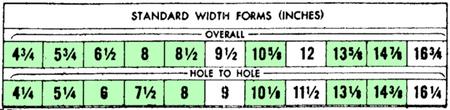

The 407 operating manual described how to design forms for the 407,20 and listed eleven standard form sizes (below).21 Despite the switch from 5/32" characters to much narrower 0.1" characters, most of the new standard form widths matched the earlier 402 widths (indicated in green). Many of the previous strange form widths (such as 17 25/32") were dropped, but 13 5/8" and 14 7/8" were preserved, which will prove important.

The IBM 1403 printer (1959) and its 132 columns

Finally we arrive at the 1403 line printer (1959). This printer supported line widths of 100 character, 120 characters, and 132 characters at 10 characters per inch. The 120 character line is obviously useful for backward compatibility with the 407. But what about 132 characters?

Note that the 13 5/8" form conveniently fit the 407's (or 1403's) 120 character line with a small margin.23 The next-larger standard form width was 14 7/8". The increase of 1.25 inches allows you to add 12.5 characters.24 Thus, the jump from 120 to 132 characters was an obvious product improvement since it makes use of the next standardized form width. One objection is that 130 seems like a more sensible round number—the UNIVAC printer used 130 characters per line—so why not use 130 instead of 132? Due to the complex alignment between the 1403's chain and the print hammers, a line width divisible by 3 (such as 132) works out better.25 I suspect this is the primary reason that the IBM 1403 used 132 characters rather than 130.26 A width of 128 might seem better because of binary, but it's not; the 1401 was a decimal machine so there's no benefit to 128.27

Conclusion

To summarize my hypothesis,28 the 132-character line on 14 7/8" wide paper has its roots in the dimensions of punch cards over a century ago. IBM's early 45-column punch cards resulted in the creation of a printing mechanism with a wide character spacing of 5/32" to match the punch card hole spacing. Even though IBM moved to 80-column cards in 1928, accounting machines continued to use 5/32" characters in the 1930s and 1940s. This resulted in standardized form widths, most importantly 14 7/8" which fit a line of 88 characters. In 1949, IBM's tabulators moved to a standard 10 characters per inch spacing. With that character size and 14 7/8" paper, a 132-character line is natural, and this was implemented on the IBM 1403 printer in 1959.

Because the 1403 printer was wildly popular, 132 character lines on 14 7/8" paper became a de facto standard supported by many other companies. This is why even though punch cards are long obsolete, you can easily buy 14 7/8" green-bar line printer paper to this day.

I announce my latest blog posts on Twitter, so follow me at @kenshirriff for future articles. I also have an RSS feed. I've written about accounting machines before, here and here, if you want to learn more. Thanks to Dag Spicer and Sydney Olson (CHM) and Max Campbell (IBM Archives) for research assistance.

Notes and references

-

I've been wondering about 132 columns for a long time. I asked the 1401 restoration team about 132 columns a while ago, but didn't get any solid answers. Retrocomputing StackExchange discussed the source of 132 columns last year, but I find the answers unconvincing. ↩

-

It's interesting to look at the history of printers and their assorted line widths.

IBM kept old printing technology around for decades. The print mechanism from the 407 (1949) was reused in the IBM 716 and 717 printers for the IBM 700 series vacuum tube mainframes (1952+) and the IBM 7000 series transistorized mainframes (1958+). The IBM 407 was also used as an output unit for the IBM 650 drum-based computer (1955) and IBM 305 RAMAC disk-based computer (1956). The IBM 1132 printer for the low-end IBM 1130 computer (1965) also used the 407's print mechanism.

IBM introduced high-speed wire printers (i.e. dot matrix) in 1955, which output 1000 lines per minute; the 719 printer had 60 column output, while the 730 had 120 columns. Unlike modern dot matrix printers, these printers had multiple print heads (30 or 60) for high speed. Unfortunately, these printers were unreliable and a commercial failure. (For details see pages 484-486 of IBM's Early Computers and the Manual of Operation.)

The RAMAC system (1956) used the IBM 370 printer (unrelated to the later IBM System/370 mainframe), which printed 80 character lines at 10 characters per inch. This printer was very slow; it took about 2 seconds to print a line using a single octagonal typestick (manual).

In 1970, IBM introduced the IBM System/370 along with the IBM 3211, a new high-speed (2000 lines per minute) line printer. This printer had 132 columns or optionally 150. It was similar to a chain printer except it used a train of character slugs.

I don't have as much information on non-IBM printers, but in 1954, Remington Rand introduced the first high-speed drum printer, the "High Speed Off Line Printer System" for the UNIVAC computer. This printer produced 600 lines per minute at 130 characters per line. The printer used 18 kW of power and was cooled by 8 gallons per minute of chilled water (details, details). As far as other manufacturers, Analex produced a 120-column line printer. Bull had a printer with 80 print bars and a 92-character alphabetical printer Samsatronic had a 140-character dot matrix printer in the 1950s. Burroughs introduced a fast (1000 line per minute) dot matrix printer (called a wire printer) in 1954 that printed 100 character lines. The Burroughs 220 High-Speed Printer System (1959) used a drum to produce 120 character lines at 1225 lines per minute.

For an extensive history of printers, see Print Unchained: 50 Years of Digital Printing, 1950-2000 and Beyond. IBM's Early Computers has a detailed discussion of the history and development of IBM printers (Chapter 12.4). It doesn't mention the reason behind different line lengths, unfortunately. For information on printing dimensions of IBM's printers of the 1970s, see Form Design Reference Guide for Printers. More information on early printers can also be found in The U.S. Computer Printer Industry. ↩

-

The estimate that half of the continuous forms volume was printed on IBM 1403 printers is from Print Unchained: 50 Years of Digital Printing, 1950-2000 and Beyond page 102. The estimate is attributed to "one observer" at "some point in the latter 1960s." The IBM 1403 had a long life; IBM 360 and IBM 370 mainframe systems used it into the 1970s. ↩

-

As a measure of the popularity of 14 7/8" forms, in 1971 that width was estimated to make up 50% of forms. (Computer Industry Annual, 1971, p309.) ↩

-

Although line printers are best known for using 14 7/8" wide paper, the IBM 1403 printer supported forms from 3 1/2" to 18 3/4" wide; see IBM 1403 Printer Component Description pages 11 and 12. Note that the printable region is 13.2", so forms can be much wider than the printable region. ↩

-

Confusingly the word "tabulator" was used for two totally different types of machine. Originally, a "tabulator" was a person, "one who tabulates, or draws up a table or scheme" (OED, 1885). The first type of machine using the name "tabulator" was Hollerith's punch-card machine that processed punch cards for the 1890 census, leading to the Hollerith Integrating Tabulator. Note that these tabulators generated output on counter dials (below); they didn't print any output, tabular or otherwise.

Hollerith Electric Tabulating System (replica). Cards were manually fed into the reader on the right, and results were counted on the dials.The second type of tabulator was the tabulating typewriter (1890). These devices were simply typewriters with tab stops to make it easier to produce tables. (The "tabulating key" on these typewriters is is the root of the "tab" key on the modern computer keyboard.) The decimal tabulator (1896) added multiple tab keys that would tab to the proper location for a 1-digit number, 2-digit number, 3-digit number, etc.

Underwood 6 typewriter with decimal tabulator (1934). Inset shows the decimal tab keys enlarged: "Tab Stop Clear", ".", "1", "10", "100", "1000", "Tab Stop Set". Interestingly, the platen scale shows 132 tick marks. Photo courtesy of J Makoto Smith.Later IBM punch card tabulators included a printer and printed tabular output, so they were tabulators in both senses. Soon afterward, IBM stopped calling them tabulators and changed the name to Electric Accounting Machine or EAM (1934). ↩

-

In the 285 tabulator, the last type bar in a print bank often had an asterisk or "CR" symbol rather than numbers. An asterisk was used to indicate a subtotal, and "CR" indicated a credit (negative number). ↩

-

Why did IBM's early punch cards have 45 columns with 5/32" spacing? See The Punched Card for history. The short answer is 28-column cards (from the 1890 census) used 1/8" holes with 1/8" between holes. The gap between holes was halved to 1/16" for 36-column cards, and halved again to 1/32" for 45-column cards, yielding 5/32" spacing. ↩

-

IBM's early interpreters printed 45 columns of numeric-only data, on short 34-column cards, 45-column cards, or "modern" 80-column cards (details). (While 45-column cards were originally thought to have almost unlimited capacity to meet all requirements, the increase to 80 columns was soon necessary.) In the 1950s IBM introduced alphabetic interpreters that could print 60 columns of alphanumeric information on a punch card. The IBM 552 interpreter used 60 type bars. The IBM 557 interpreter (1954) switched to 60 typewheels. Apparently, the IBM 557 had reliability problems and later 60-column interpreters went back to type bars: the IBM 548 and IBM 552 (1958 and 1957). ↩

-

The high quality of the IBM 1403's print was largely due to the use of a horizontally rotating chain. Earlier printers used type bars, type wheels, or drums. These approaches have the problem that any error in timing or positioning results in characters that are shifted vertically, resulting in objectionably wavy text. On the other hand, positioning errors with a type chain are horizontal, and people are much less sensitive to type that is spaced unevenly. ↩

-

Why would customers care about standard form sizes? The 407 reference manual stated that forms of standard sizes can be obtained more quickly and economically from forms manufacturers than non-standard sizes. In addition, when using the pin-feed platen, the platen dimensions had to match to the form width. IBM had standard platens to match the standard form sizes (see 923 parts catalog page 16), but non-standard forms required a custom platen. ↩

-

Accounting machines added support for continuous forms in several steps. On early tabulators, the operator needed to stop the machine and manually advance the paper to the top of each form. The IBM 921 Automatic Carriage (1935) provided a motorized mechanism to automatically jump to the top of a form or a particular position on the form. But even with an automatic carriage, the operator needed to ensure the forms didn't slip out of alignment (especially multiple-copy forms with carbon paper). Standard Register Co. solved this problem in 1931 with the pin-feed platen driving forms with feed holes along the edges. IBM tabulators supported these forms with a pin-feed platen or the IBM F-2 Forms Tractor (407 Manual p70). By 1936, Machine Methods of Accounting stated, "The use of continuous forms in business has been increasing at a rapid pace in recent years due to the perfection of more and better mechanical devices for handling such forms." ↩

-

The standard form widths had a long lifetime, with most of them still available. The book Business Systems Handbook (1979) has a list of typical widths for continuous forms: 4 3/4", 5 3/4", 6 1/2", 8, 8 1/2", 9, 9 1/2", 9 7/8", 10 5/8", 11, 11 3/4", 12, 12 27/32", 13 5/8", 14 7/8", 15", 15 1/2", 16", 16 3/4", 17 25/32". (18 15/16" is the only standard IBM size missing from this list.) Even though IBM dropped many sizes in their 407 standard list (such as 12 27/32" and 17 25/32"), they were unsuccessful in killing off these sizes. ↩

-

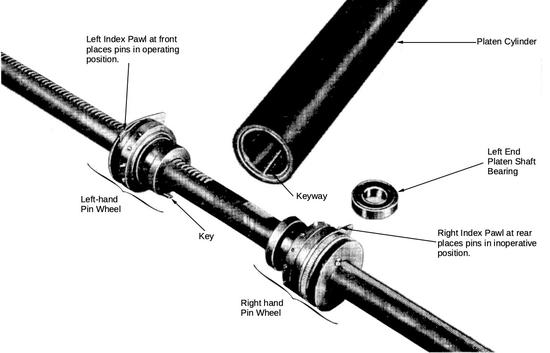

A major part of my analysis is that the standard form hole-to-hole width is typically divisible by 5/32" (although not always). I couldn't find a stated reason for this, but I have a theory. To support continuous forms, pin wheel assemblies (below) are attached to the ends of the platen cylinder. Consequently, the hole-to-hole distance is determined by the platen width. It makes sense for the platen width to be a multiple of 5/32" so characters fit exactly. The distance from the edge of the platen to the pin centers appears to be 5/32". (I measured pixels in photos to determine this; I don't have solid proof.) Thus, the hole-to-hole distance will also be a multiple of 5/32"

The pin-feed platen consists of two pin wheels that go on the end of the platen cylinder. Adapted from IBM Operators Reference Guide (1959) page 80.Many of the standard IBM form widths are divisible not only by the character width (5/32") but also divisible by the width of 4 characters (5/8"). I found a mention in Machine Methods of Accounting (page 17-1) that the IBM 405's original friction-feed carriage was adjustable in units of 4 characters, held in position by a notched rod. This suggests that these widths were easier to configure for mechanical reasons. ↩

-

The IBM 285 tabulator was configured with 3 to 7 print banks, each 1 7/8" wide. (See Machine Methods of Accounting: Electric Tabulating Machines page 14.) I believe these were the source of the standard form widths 8", 9 7/8", 11 3/4", 13 5/8" and 15 1/2" (after adding some margin). Many of the other standard sizes are nice round numbers (e.g. 11" and 16"). 18 15/16" was probably selected to yield 18" paper (Arch B) with the punched margins (actually 1/16" smaller than 18" so the hole-to-hole width is a multiple of 5/32"). I can't come up with any plausible explanation for 17 25/32", but it may be related somehow to 17" ledger paper (ANSI B) or perhaps untrimmed paper sizes (SRA2, Demy).

The 12 27/32" width was derived from loose-leaf accounting binders, which date back to 1896. In 1916, the Manufacturers of Loose Leaf Devices held a meeting in Atlantic City to establish standard sizes. They decided on 9 1/4"×11 7/8", 11 1/4"×11 7/8" and 7 1/2"×10 3/8". The standardization was successful since the smaller two sizes are still available today. To support the 11 7/8" ledgers, IBM apparently shaved off 1/32" to make the hole-to-hole width divisible by 5/32", yielding 11 27/32". Adding the 1/2" punched margins on each side results in the standard form width 12 27/32". While loose leaf may not seem exciting now, Office Appliances (1917) has a remarkable description of the victory of loose-leaf ledgers over "Prejudice, Indifference, Distrust" so they now "stand supreme as Leaders in modern progressiveness" in the "battle for Modern Efficiency". ↩

-

Standardized tabulator form sizes were so prevalent that special business form rulers were produced to help design business forms. These rulers had markings indicating standard form widths and 5/32" and 0.1" scales for tabulator character spacing. These rulers are still available. ↩

-

Since the 14 7/8" standardized width is very important, I'll discuss the math in more detail. The 405 accounting machine had 88 type bars, but there was one blank space (for a ribbon guide) between the alphanumeric and numeric type bars. Thus, the printing region was 89 × 5/32" = 13 29/32" wide. (As mentioned before, this just fits (probably by design) onto a 14" unperforated page.) Since standard perforated forms had 1/2" marginal perforations on each side to remove the holes, reasonable form widths would be 14 29/32" or 15". These values are not divisible (hole-to-hole) by 5/32"14. However, since the 402's characters have excessive white space around them, the characters still fit if we trim off 1/32" from the width. This yields a 13 7/8" line. Hole-to-hole, this is 14 3/8", divisible by 5/32" and even better 5/8". Adding the perforated margin, this yields 14 7/8" width as the "best" size to support the 405's 88-character output. (This seemed like random math, even to me, at first. But since the same approach explains the 12 27/32" width, I'm reasonably confident it's the right approach.) ↩

-

Why did the 405 accounting machine (1934) and 402 accounting machine (1948) have 88 print positions? The accounting machines had a 43-column alphabetical print unit and a 45-column numeric-only print unit (below), with a 5/32" gap between for the ribbon. I think these type bar print units were derived from the 45-column type bar print unit used for the IBM 550 interpreter (1930), since they have the same 5/32" character spacing. But that raises the question of why two columns are missing from the alphabetical print unit. The 405's line of 88 characters with a gap between the units just fits onto a 14" page. (A 14" page without holes, friction-fed.) This is mentioned in Alphabetic Accounting Machines (1936) page 17-2, so it's presumably deliberate. So I think they used 88 columns instead of 90 in order to fit on 14" paper. ↩

-

I talked to an old IBM engineer who serviced a company's collection of 407 tabulators as a new engineer, but after cleaning the type wheels he didn't put enough oil on them. A couple weeks later, the type wheels started seizing up and would hit the platen at high speed, sawing notches into the platen. (The platen is the roller that the paper goes around.) He used up IBM's entire East Coast collection of platens to fix these tabulators. He was afraid IBM would fire him over this, but they were supportive of engineers and he stayed for a long career. ↩

-

The design of business forms was a complex task. The book Business Systems Handbook (1979) has a 30-page chapter discussing forms design, including how to meet customer needs, determining the size and layout of the form, and ideas on form techniques for various purposes. ↩

-

In the 1970s, IBM still had 11 standard form widths, but there were a couple changes from the 407 era. An IBM patent mentions this in a vague way; apparently the 16 3/4" width was dropped and 11" added. ↩

-

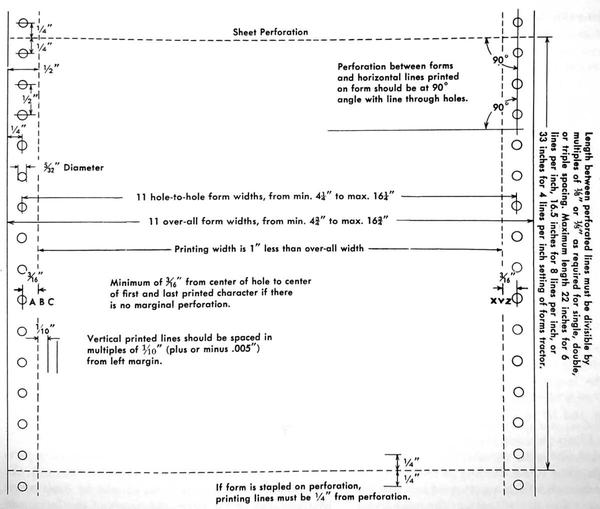

The diagram below gives some information on the dimensions of forms for the IBM 407 accounting machine.

IBM's recommended specifications for forms. From Reference Manual, IBM 407 Accounting Machine.One important takeaway from this diagram is that the printing width is 1" less than the overall form width. It's interesting to note that the hole width is 5/32", exactly the same as the character width on a 402 accounting machine. ↩

-

A width of 13 5/8" gives a printable region of 12 5/8". This fits 120 characters with 5/8" of extra space. A margin makes it easier to align the paper so characters fit between the perforations. Note that a margin is more important with 0.1" characters than 5/32" characters because the wider characters are already surrounded by white space. ↩

-

Using 14 7/8" paper gives a printable region of 13 7/8" (13.875"), so you could fit 138 characters on a line. I couldn't find any 138-character printers, but several used 136-character lines. CDC in particular liked 136 columns, as shown by the CDC 501 line printer and later CDC 580. The book Print Unchained. said that 136 columns was a European width, but I haven't been able to find any line printer models fitting this. Later dot matrix printers from Epson, Datapro and other companies often supported 136 columns. ↩

-

The timing of the 1403 printer is fairly complicated; I've made an animation here to illustrate it. The important thing for the current discussion is that every third character position gets a chance to print in sequence, so the printer makes three "subscans" to cover all the character positions. Thus, it makes sense for the line length to be a multiple of 3 so all the subscans are equal. Obviously it's possible for the 1403 printer to support a line length that isn't a multiple of 3, since some 1403 printer models supported 100-character lines. ↩

-

This may be numerology, but it seems that IBM liked increasing print capacity in steps of 12. On the IBM 285 accounting machine, this made sense since each print bank was 12 characters wide. The IBM 407 accounting machine had 120 columns. The IBM 1443 printer (1962) had line lengths of 120 or 144 characters (2*12 characters more). So it seems plausible that the 132 column line was considered reasonable as it added one more 12-character column. ↩

-

You might think that 128 characters per line would be more convenient since it's a power of 2. However, the IBM 1401 was a decimal (BCD) machine with decimal addressing. (For instance, it had 4000 characters of storage, not 4096.) Since it needed to count the line in decimal, there is no hardware advantage to 128. ↩

-

To summarize the summary: 88 × 5/32" ≈ 132 × 0.1" (with a bit of margin) ↩

11 comments:

That explains the oddball text-mode video modes of SVGA video cards. 0x109 = 132x25, 0x10A = 132x43, 0x10B = 132x50, 0x10C = 132x60.

Indeed, although there's another step in between. When video terminals started to take over from teletypes, they were most often available in 80-column (after the 80-column punch card and 80-column printer) and 132-column (after the 132-column printer). The VT52 was 80x24, and the VT102 supported 80x24 and 132x24. The 25th row came later :)

Per your note 6 (tabulators referring to humans) the term computer was also used in reference to those who perform computations, most notably personnel working at Los Alamos on the Manhattan Project; see https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/human-computers-los-alamos.

Ah the memories. In the mid 80s I operated a 4341 with a 1403 printer. In the very small hours, before bulk printing, I had to clean the print train. This involved spinning the print train against an alcohol soaked cotton cloth. Young and stupid I used a paper towel instead. The print train chewed up the paper and it lodged between the slugs, jamming the mechanism.

Bleary eyed an IBM engineer turned up, disassembled, and cleaned each slug with alcohol. After reassembly it was still unexpectedly jammed. He grabbed the cup that held the alcohol, the bottom fell out, and alcohol went everywhere. The alcohol had dissolved the PLASTIC cup, that I had given him to hold the alcohol. Because of me, his meticulous cleaning had actually coated each slug with plastic. Doh!

I remember very well the 1403. It was parked directly behind the counter in the computer center where you dropped off your decks to be read into the 360. We actually had two 1403's. One of them had the TN upper/lower case print train. I still remember the JCL for requesting that: "TRAIN=UPLOW". Of course there was an extra charge for that, but many of my term papers came off that printer.

Someone had written a program to play music on the 1403. It made a ripping sound with each line it printed. The pitch depended on what was being printed. This guy figured out what set of characters to send to make specific pitches. It was very strange. The operators didn't like it though because it made the printer behave erratically.

It was also possible to make your own perforated forms by overprinting the same line multiple times. You had to be careful though you didn't chew right through the paper and cause a tear. The operators really hated that.

But what they hated the most was changing the ribbon. It was impossible to do without coming out looking like you had dunked your hands in an inkwell. It wasn't too cool to get the first job printed after a ribbon change either. The ink would be still wet on the paper and would smear on anything it came in contact with.

Those sure were the days.

Bleary eyed an IBM engineer turned up, disassembled, and cleaned each slug with alcohol. After reassembly it was still unexpectedly jammed. He grabbed the cup that held the alcohol, the bottom fell out, and alcohol went everywhere. The alcohol had dissolved the PLASTIC cup, that I had given him to hold the alcohol. Because of me, his meticulous cleaning had actually coated each slug with plastic. Doh!

Cool history!

My related story is that a friend and I each had teletype machines as printers on our home computers. They were 72 columns (which is missing from your list!). But the dot-matrix printers were all 80 columns and some software expected this. So he set about modifying his teletype to do 80 columns. The first few were easy and just involved moving some endstops. The next few required filing down some parts. The last few were really hard, but he eventually pulled it off. The best part was when he was working on getting from 79 to 80 one day with the endstops off, studying where things were stopping. He was hitting the spacebar and counting. 76, 77, 78, 79, thunk! The entire print assembly fell out and onto the desk. These were complicated beasts, and it took hours to reassemble.

The Remington Rand printer with the water-cooled spinning drum is the historical reason behind the Linux kernel warning "lp0 on fire".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lp0_on_fire

And here's some music from a 1403 printer:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jufHGUp3xQw

Regarding adding 12 columns at a time, this seems like a sensible size which allows for a lot of flexibility.

It would allow for one field with a leading space for margin, seven digits, a period, and a trailing space for margin -- good for a value of a million dollars (9,999,999.99 max). And if you drop the margins and period you accommodate one shy of a billion.

Or two columns with four digits and padding, etc.

A consideration not mentioned is that IBM was a marketing-driven company. Going from 120 to 132 columns was a 10% increase, easy to tout.

A friend of mine ran an IBM 1130 at a high school in NYC. As you describe, the 1132 printer used a 407 type-wheel mechanism. The print hammers for each character position were actuated by solenoids driven by a power transistor. From time to time, a transistor would fail, resulting in a character position that would not print. While waiting for IBM field service, my friend would determine which print position had failed and swap the corresponding SMS circuit card with the SMS card for the final print positions, Doing this moved the bad character to the end of the print line, which was rarely used by student programs.

In the late 1970's I programmed an IBM 1401 computer with a 1403 line printer attached in FORTRAN IV. (I was in high school then and did not yet comprehend how insanely clever the FORTRAN compiler for the 1401 was. We had 12000 characters of core memory but that compiler could actually run in 8000.)

The School District got an "educational" discount on the 1401 rental contract if they let students use it some of the time, so there was one high-school computer-science class per year in the summer term only, and the machine was made available to the "computer club" under the supervision of the computer-science teacher four hours per week during regular terms. Only CS students used the FORTRAN compiler; all the District's business software was developed in Autocoder.

There was a way to drive the 1403 printer insane, so that it would suddenly start to feed paper at terrific speed, causing a giant ribbon of paper to shoot out the back of the printer and making a frightening noise.

When this happened, pressing the normal STOP button (which appeared on multiple devices, including the line printer, the CPU, and the card read/punch unit) would have no effect. The line printer didn't care if the CPU was running. You had to find and press the CARRIAGE STOP[FN1] button on the printer, or...

We were instructed, in case of printer runaway, to step in the open box of fan-fold paper beneath the printer! The printer would tear off the paper at a page-perf and then sit there whining loudly until someone pressed the proper button to stop it.

This excitement would occur if your FORTRAN program caused a bogus character to be emitted in the first, carriage-control column of an output line to be printed. That was programmer error: typically you had forgotten the customary 1H_ at the start of some FORMAT spec so the first character on the line was the arbitrary leftmost-character of whatever you intended to print out. Of course when intentionally varying carriage-control to print fancy stuff, the printer could act as an (unwanted) klaxon to indicate your code was buggy.

Post a Comment