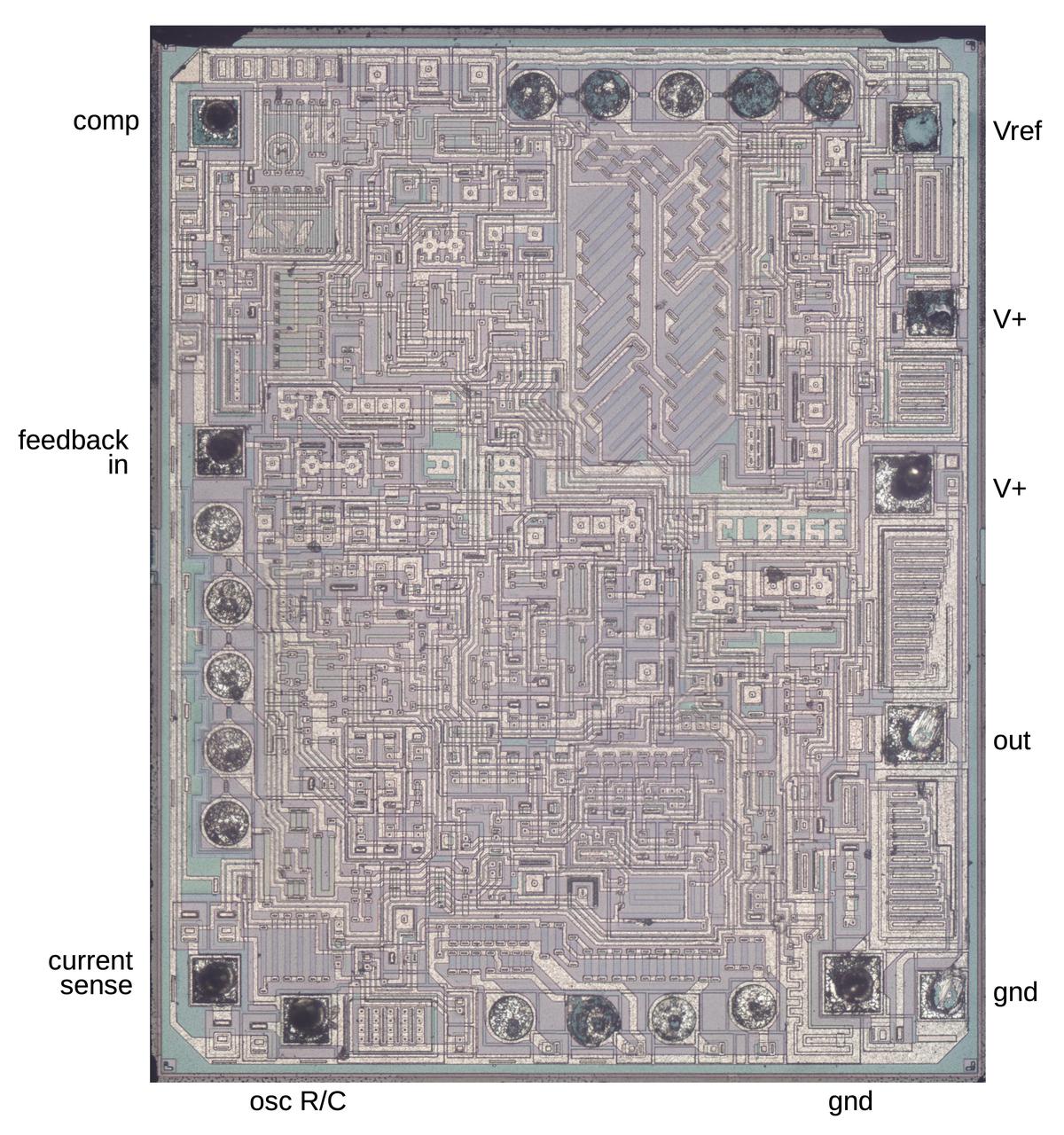

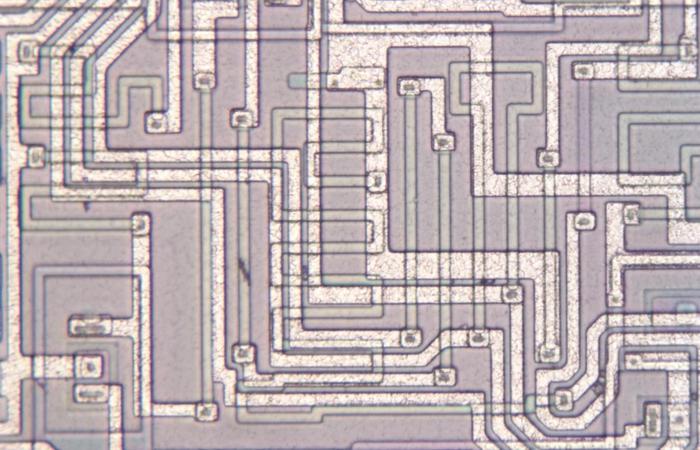

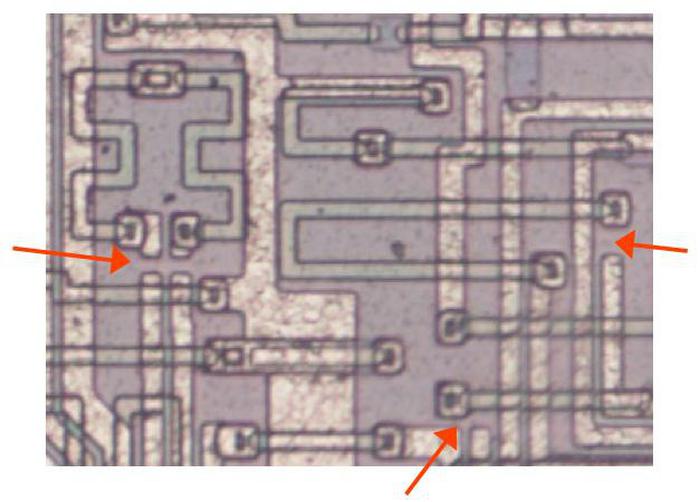

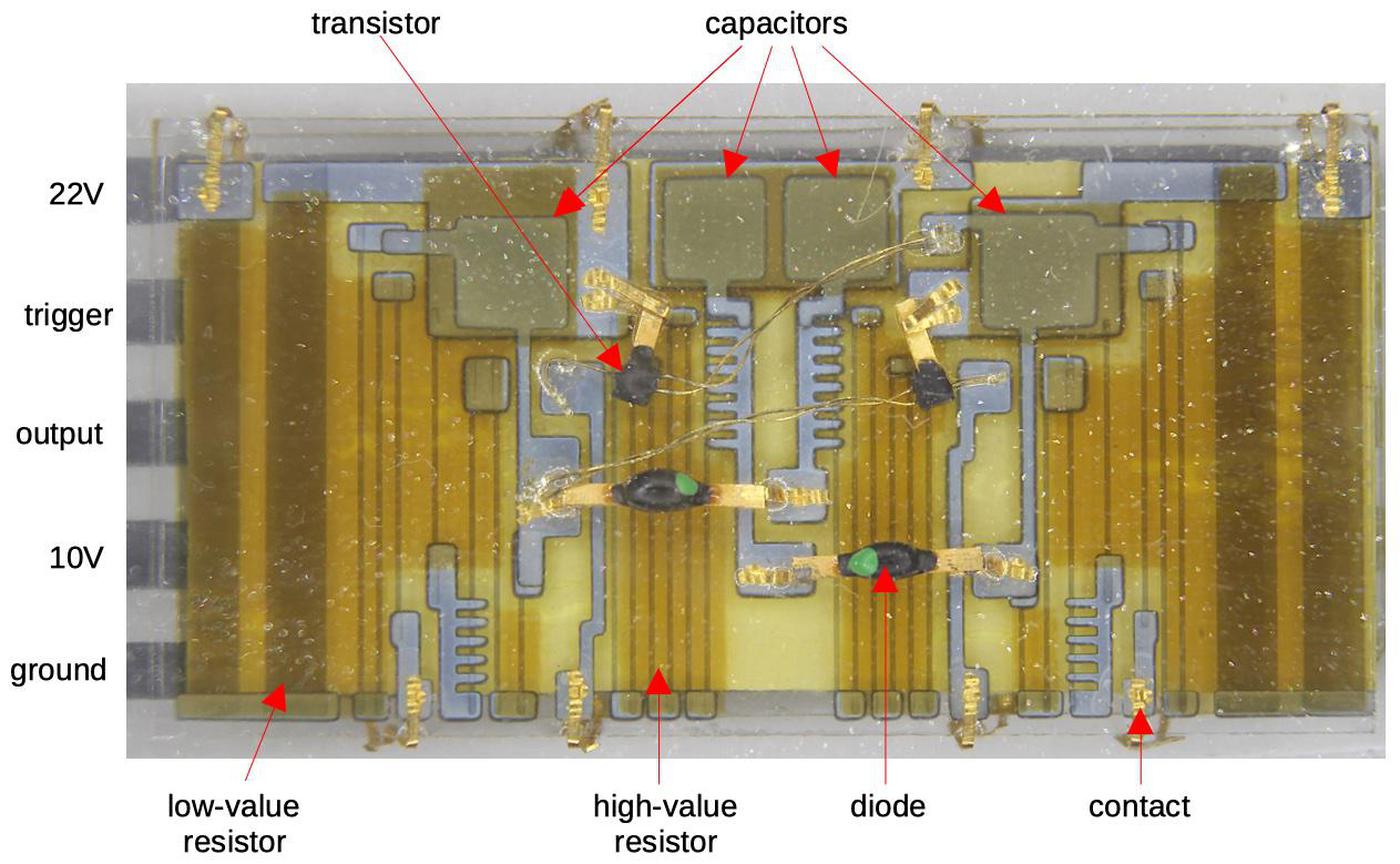

I recently did a PC power supply teardown so I figured it would be interesting to go deeper and see what happens inside the power supply's control IC. The die photo below shows the UC3842 chip, which was very popular in older PC power supplies.1 (The chip was introduced in 1984 but this die has a date of 2000.) The tiny silicon die is patterned to create the transistors, resistors and capacitors that make up the circuit. The lighter-colored lines are the metal layer on top of the silicon, forming the chip's wiring. Around the edges, square pads provide the connections from the die to the IC's external pins; tiny bond wires connect the pads to the chip's external pins.

The photo below shows the chip mounted on the power supply board. For the die photos, I extracted the die from the epoxy package by heating it and then cleaned up the die with a few drops of sulfuric acid. I took photos with a microscope and stitched them together to create a high-resolution image.

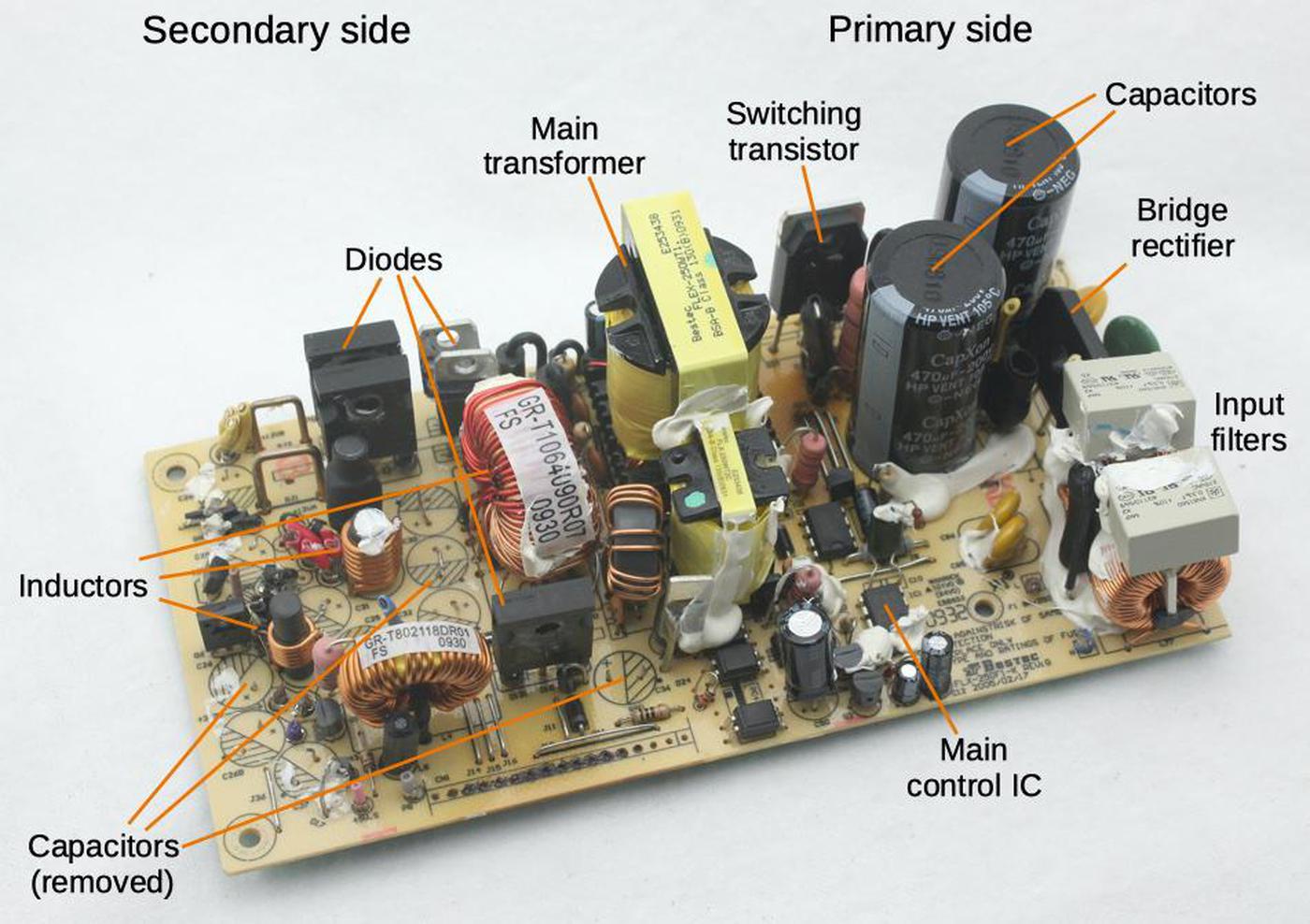

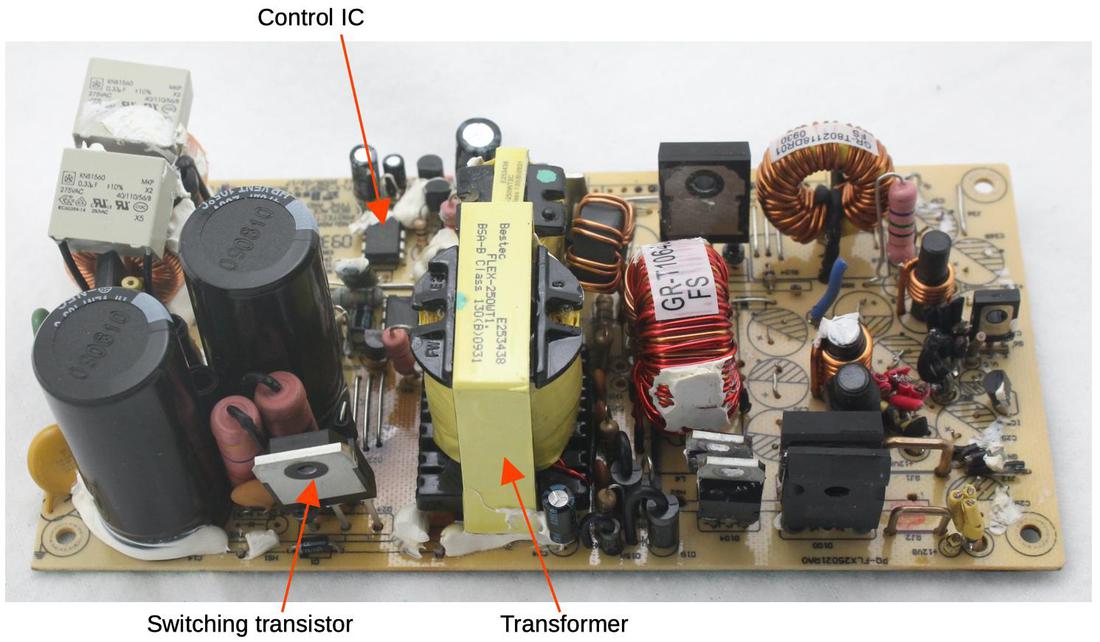

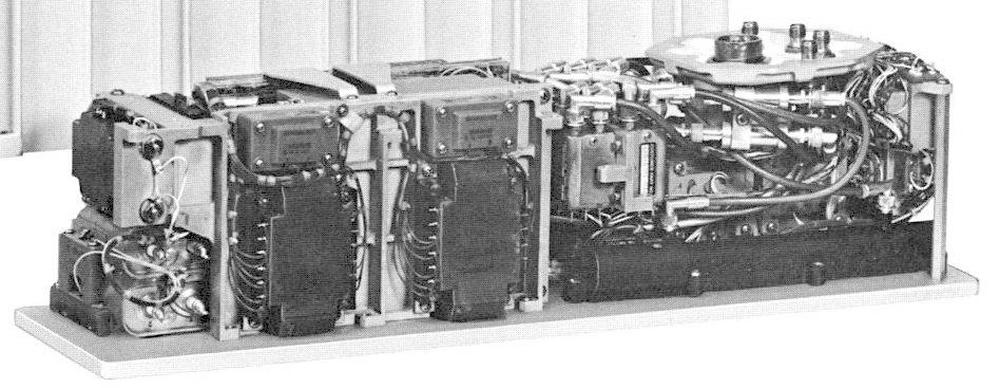

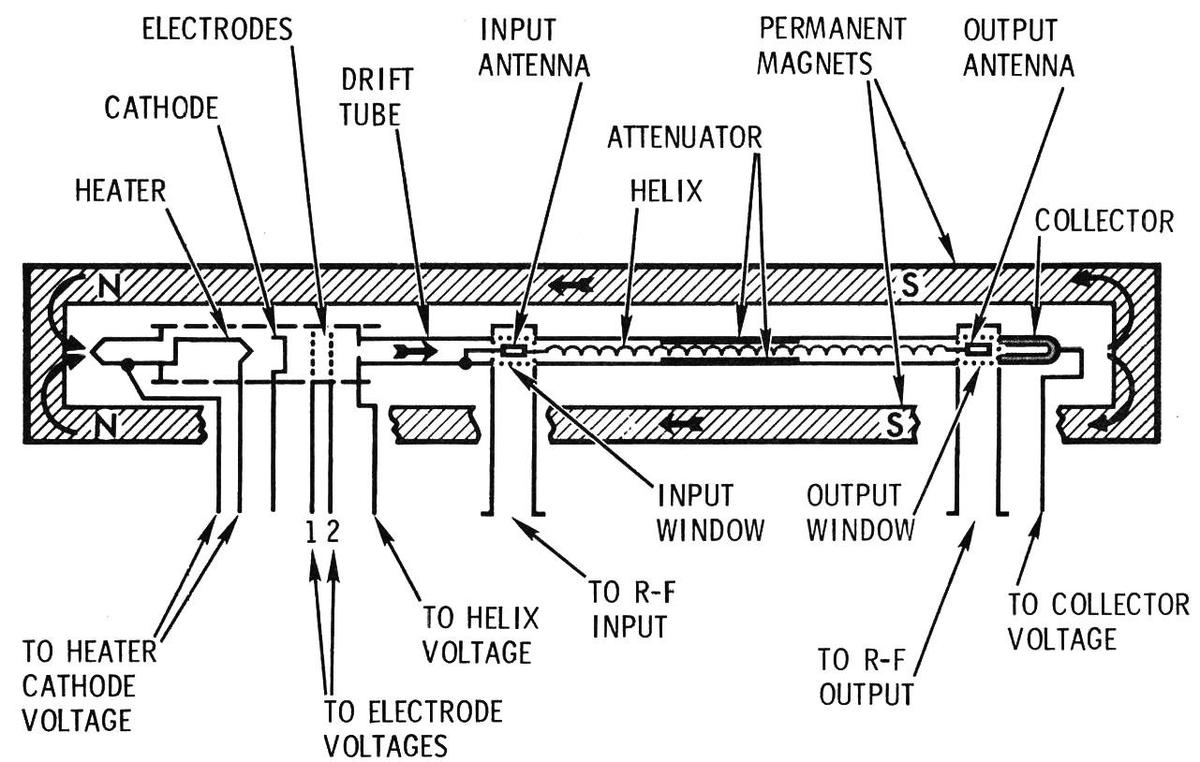

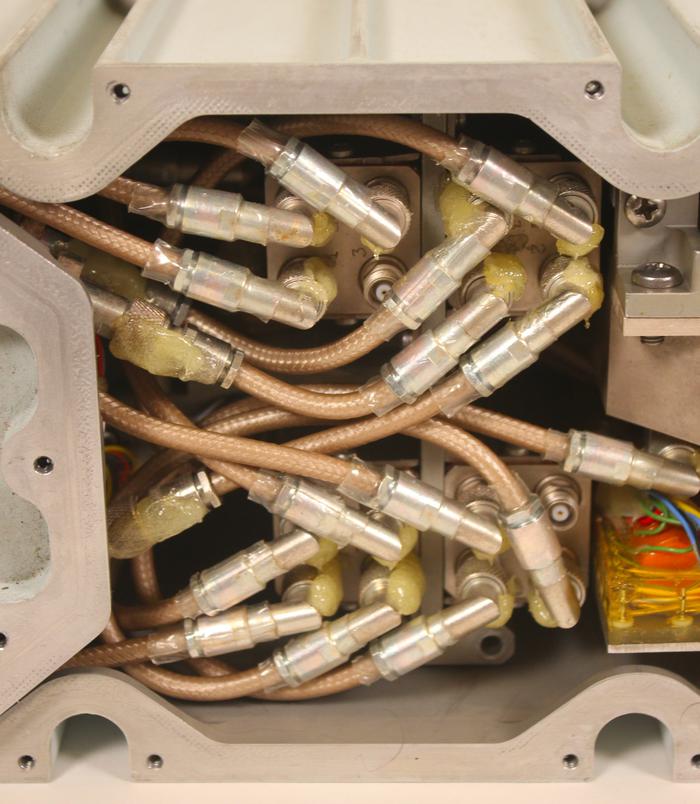

The chip is from the PC power supply below. This is a switching power supply so it uses several steps to produce the output voltages. On the primary side, the input AC is filtered and then converted to high-voltage DC (roughly 170 to 340 volts) by the bridge rectifier, and the large capacitors smooth it out. Next, the DC is chopped into pulses thousands of times a second by the switching transistor. The control IC constantly adjusts the width of the pulses to regulate the output voltage. These pulses go into the transformer, which converts the high-voltage pulses into low-voltage, high-current. The diodes on the secondary side produce the multiple DC outputs, which are smoothed by the inductors and capacitors.

This process may seem complex, but it has several advantages over putting the AC from the wall directly into a transformer. First, because the transformer operates at thousands of hertz instead of 60 hertz, a much smaller transformer can be used. Second, chopping the DC into pulses wastes very little energy, compared to a "linear regulator" that converts excess voltage into heat. The result is a power supply that is inexpensive, lightweight, and efficient.

In this blog post, I'll explain the construction of the controller IC, the building blocks of its circuitry, and how it operates. This may be a lot for one blog post, but we'll see how it goes.

Some silicon components

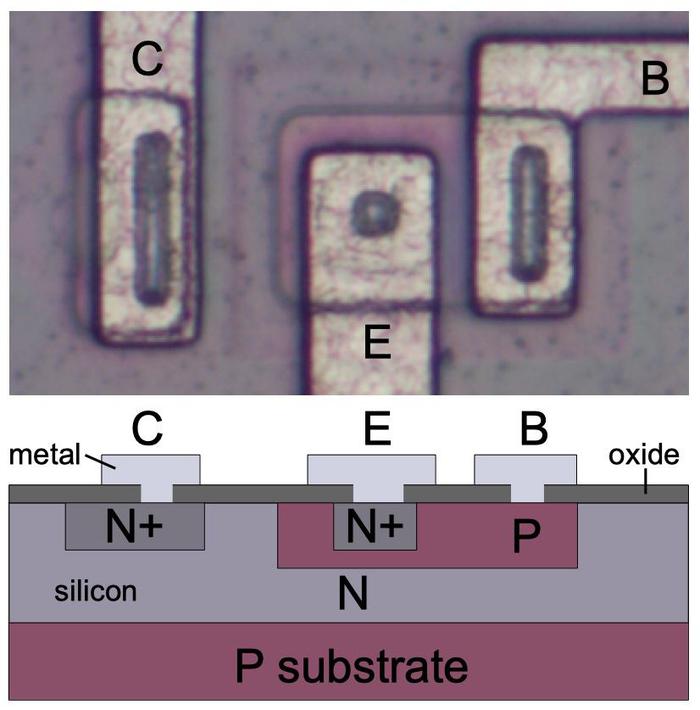

This IC is built from a type of transistor known as bipolar, rather than the MOS transistors that are typically used in modern ICs. The highly-magnified photo below shows an NPN transistor as it appears on the chip, with a cross-section drawing underneath. The metal wiring on top of the transistor is visible as the wide light-colored lines. Different regions of the silicon are doped with impurities to change its electrical properties, yielding N-type and P-type silicon. These regions are faintly visible in the photo. An oxide layer on top of the silicon provides insulation from the metal, except where a contact (black circle or oval) provides a connection between the metal and silicon.

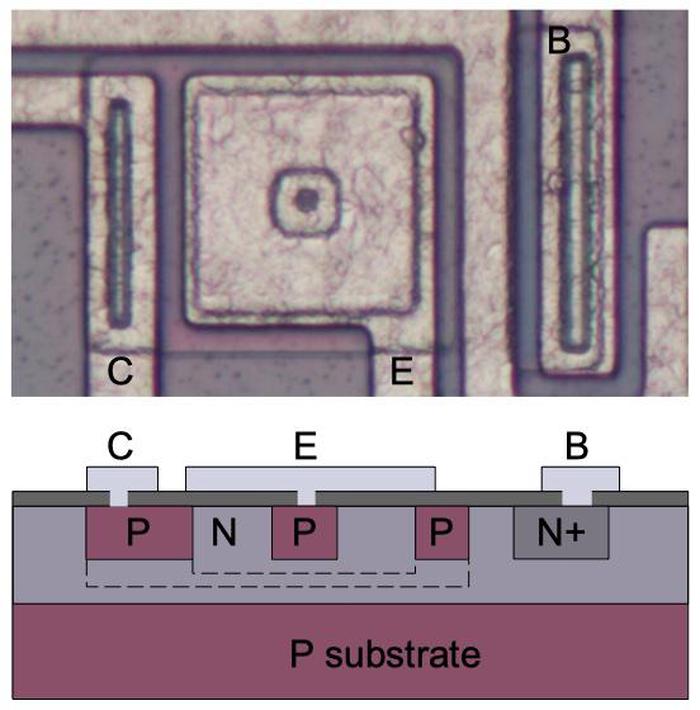

The chip also uses many PNP transistors. Although you might expect a PNP transistor to simply be the reverse of an NPN transistor, it has a different structure, with the regions arranged laterally instead of vertically. The collector and base form concentric square rings around the emitter. The base wire is not connected to the base region directly. Instead, the wire is at a distance, and the base signal travels underneath through the N layer.

Because this chip consists of mostly analog circuitry, it uses a lot of resistors. The photo below shows several typical resistors, the thin grayish-green lines. The resistors are connected to metal wires at either end, the wider metallic-looking traces. Some resistors are straight lines, while others zig-zag to fit a longer resistor (i.e. higher resistance) into the available space.

Resistors are an inconvenient component for integrated circuits. First, they take up a relatively large amount of room, especially long, high-value resistors. Second, they are inaccurate; their value can vary unpredictably from chip to chip, or even on a single chip. For this reason, circuits are typically designed so they depend on the ratio between two resistors, which is much more stable.

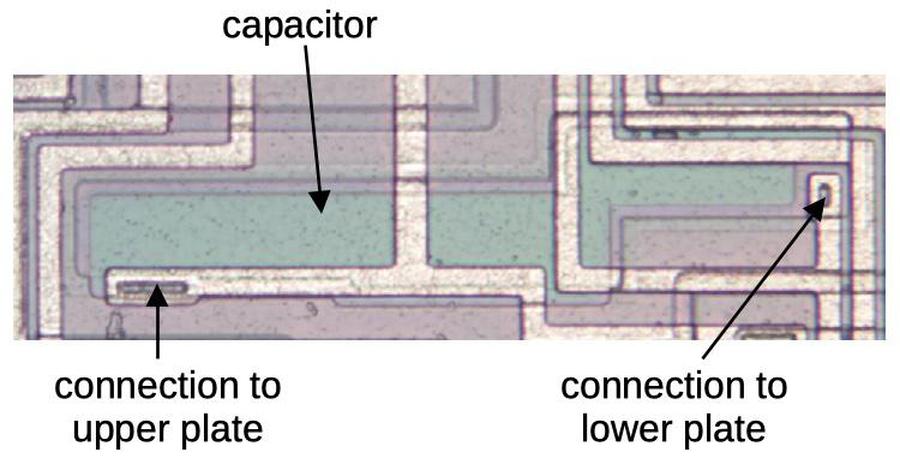

Capacitors are also bulky so the chip uses only a few, to stabilize its amplifiers. A capacitor can be formed by using the underlying silicon as one plate, and then putting a layer of polysilicon on top to form the second plate, separated by a thin layer of insulating oxide. Polysilicon is a special type of silicon, and appears green in the photo.

Architecture of the chip

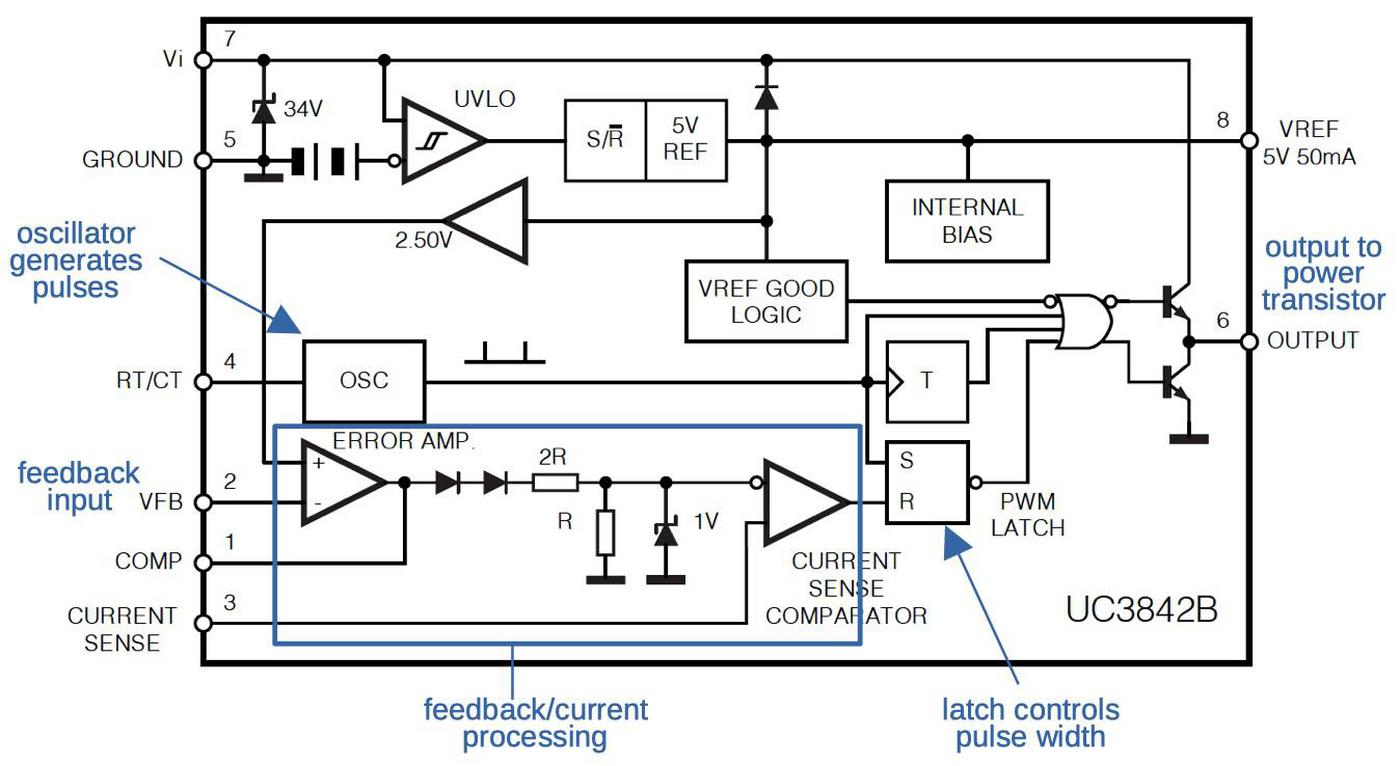

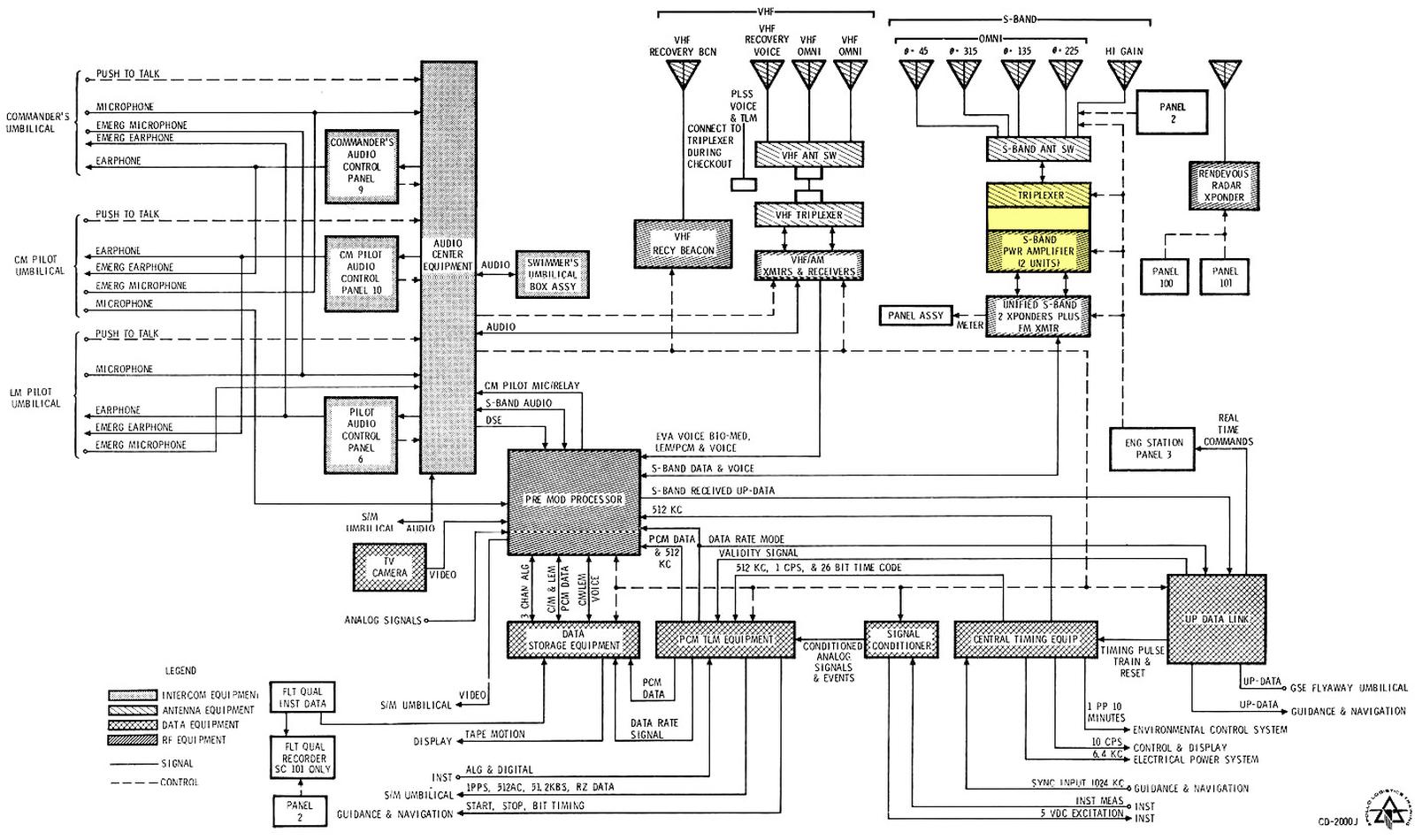

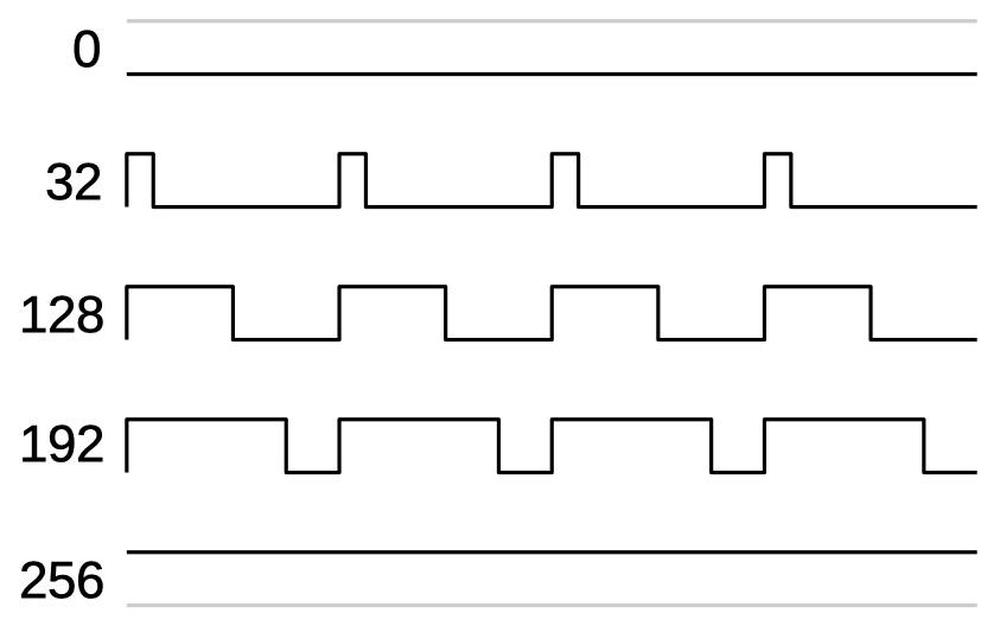

To summarize the chip, it generates pulses to control the switching transistor that feeds the transformer. These pulses are at a fixed frequency (e.g. 52 kHz), but the width of the pulses increases if more power is needed to keep the output voltage constant. The chip constantly adjusts the pulse width based on voltage and current feedback from the power supply, keeping the output voltages stable even as the load changes.

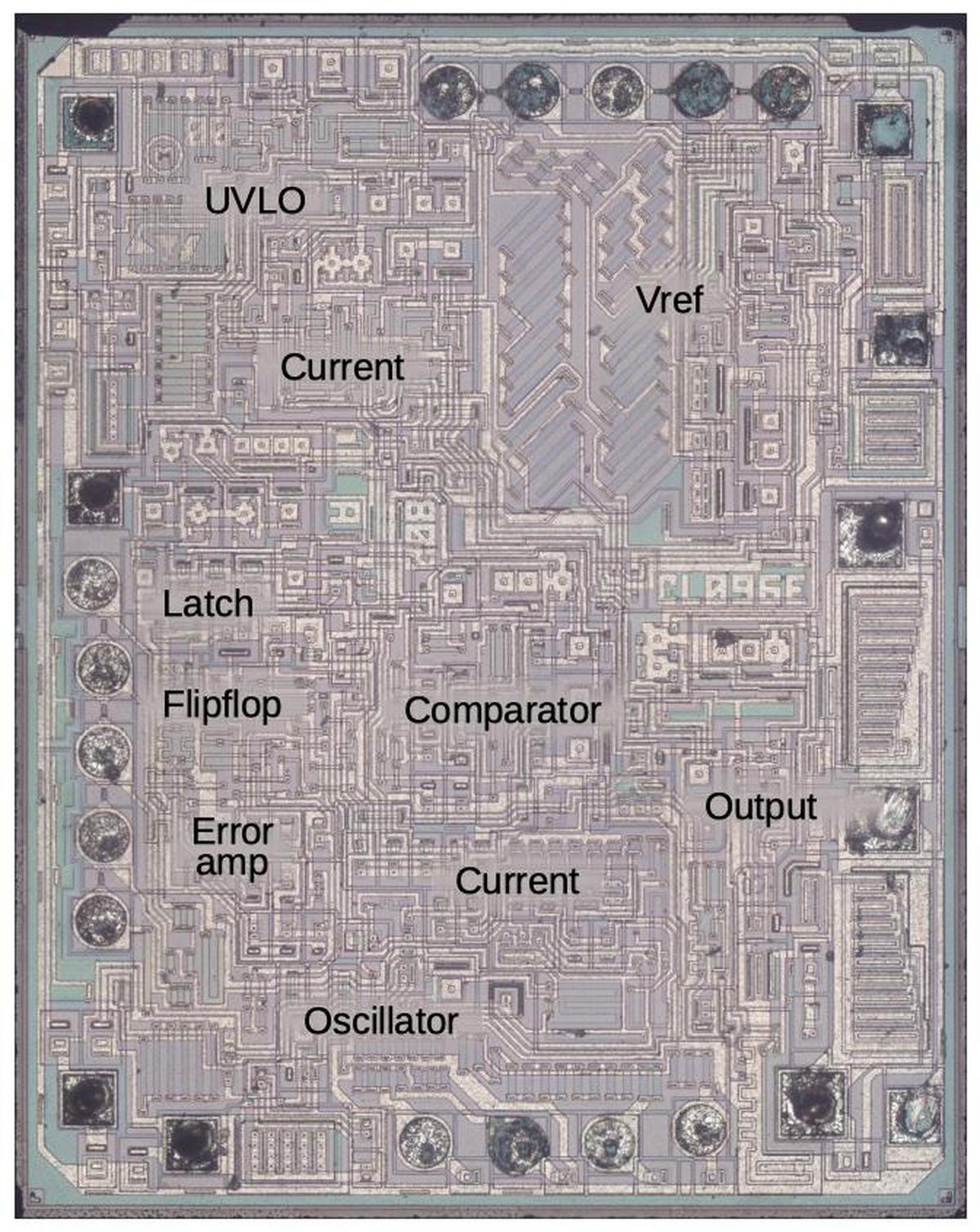

The die image above has been labeled with the main functional blocks of the chip. It can be compared with the block diagram (below) from the datasheet. I'll describe the main functional blocks before explaining how they are implemented.

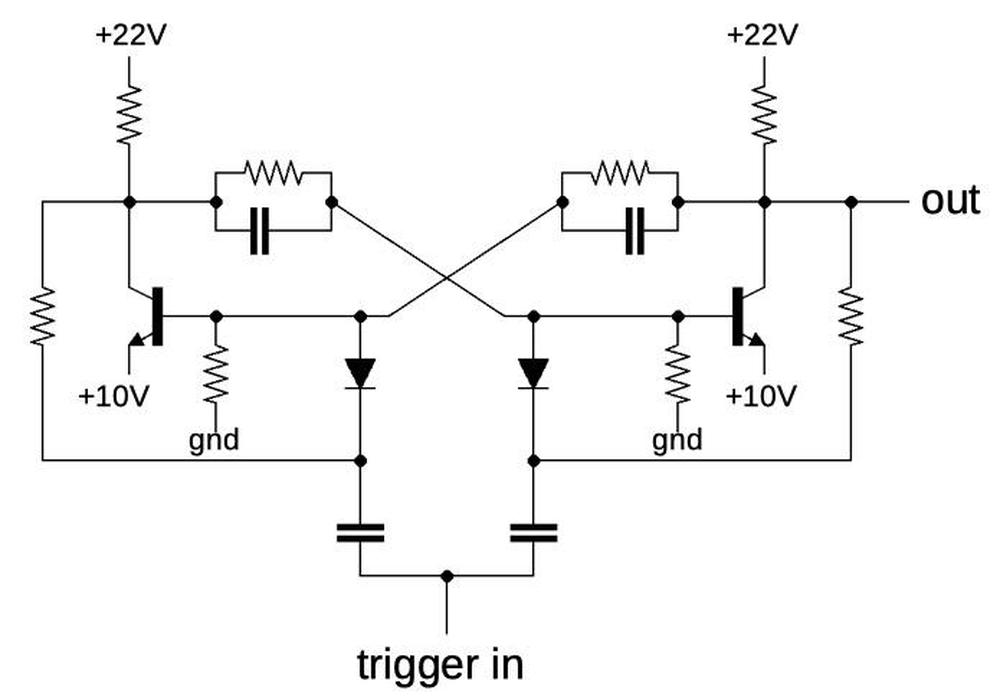

The power supply's pulses start with the chip's oscillator, which generates pulses at a frequency controlled by an external resistor and capacitor. Below the oscillator is the feedback circuitry that adjusts the pulse width based on voltage and current feedback. The PWM latch (Pulse Width Modulation) combines the oscillator signal and the feedback to generate pulses of the right duration. These pulses go to the high-current output stage, which drives the external switching transistor.

The chip itself is powered by an auxiliary winding on the transformer that provides 15 to 30 volts. The chip regulates this down to an internal 5-volt supply, using a special circuit called a bandgap regulator to keep this voltage stable within 2%, even with changing temperature. (This regulated reference voltage is also provided externally as Vref for external circuitry that needs a stable voltage.)

A potential problem is that if the power supply is unplugged (for example), the chip may behave unpredictably as the input voltage drops. To guard against this, an Under-Voltage Lock Out (UVLO) feature shuts the chip down cleanly if the input drops too low.

A final interesting feature of the chip is how it starts up. As described above, the chip is powered by the transformer, but the chip generates the pulses that feed the transformer. This seems like a chicken-and-egg problem, since the chip won't receive any power until it is already driving the transformer. The solution is a connection to the rectified line voltage through a very large resistor, so the chip receives hundreds of volts but just microamps of current. A Zener diode (below) drops this startup voltage down to 34 volts, enough for the chip to start generating pulses, at which point the transformer takes over.2

The oscillator

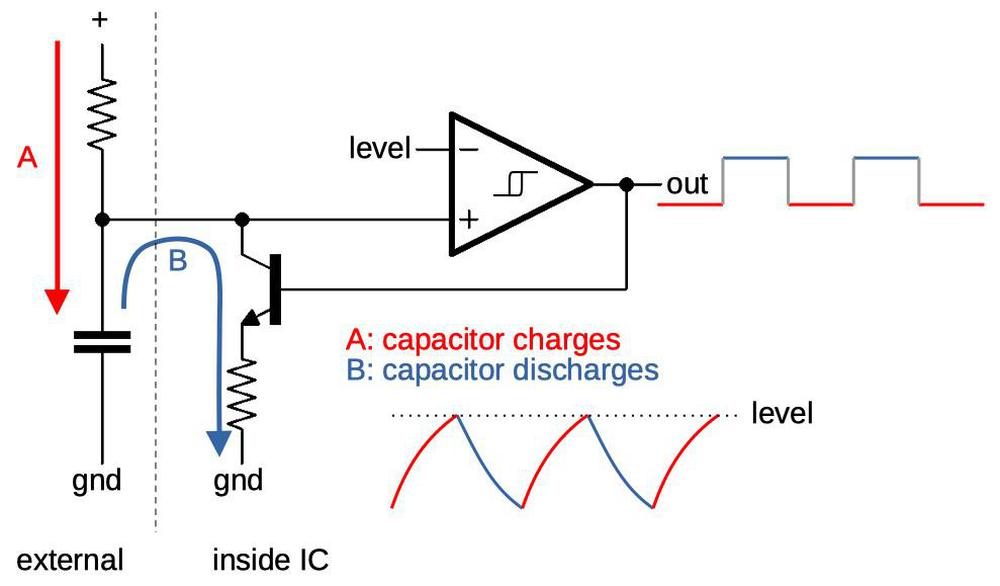

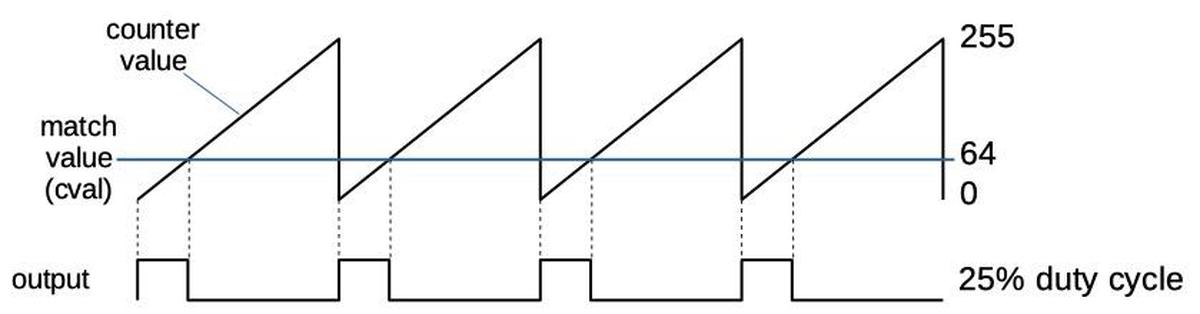

The simplified diagram below shows how the oscillator works. In the first phase (A), the external capacitor is charged through the resistor. When the voltage on the capacitor reaches a fixed level, the comparator (triangle) turns on, energizing the discharge transistor. In the next phase (B), the capacitor discharges through an internal resistor, and then the cycle starts again.3 Thus, by choosing particular values for the external resistor and capacitor, the power supply designer can select the oscillator frequency.

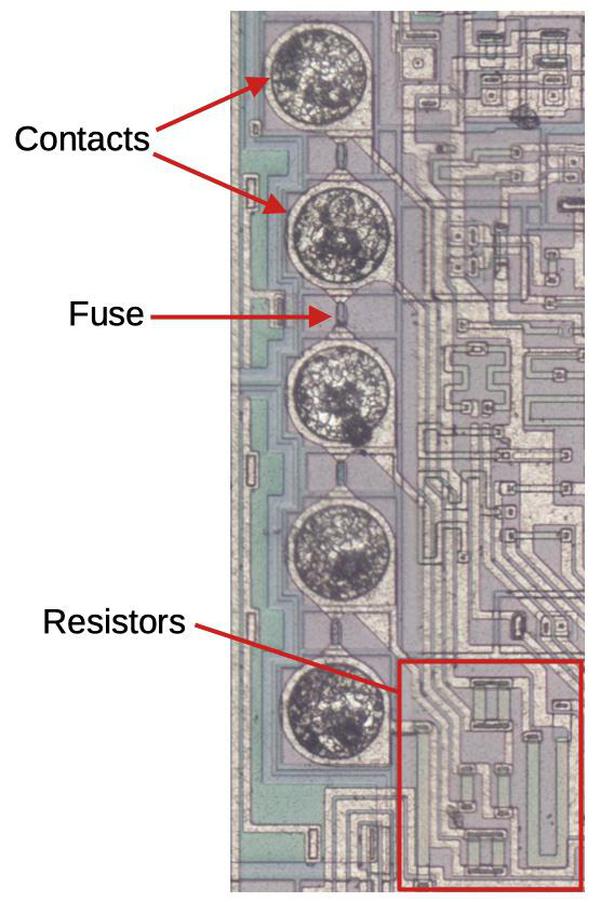

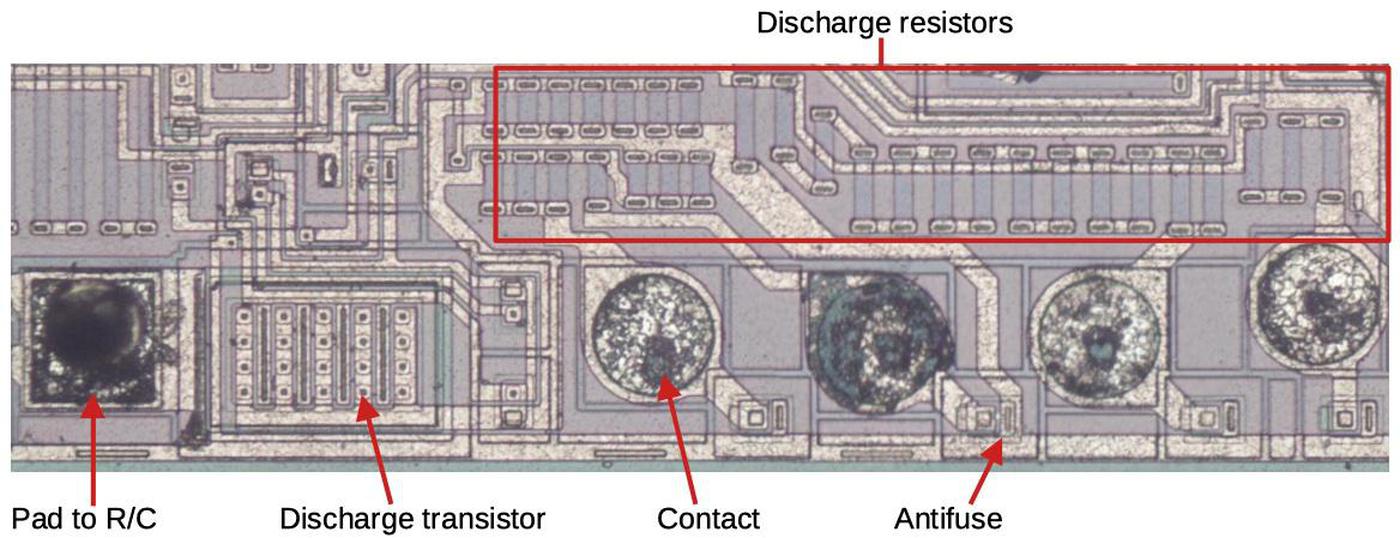

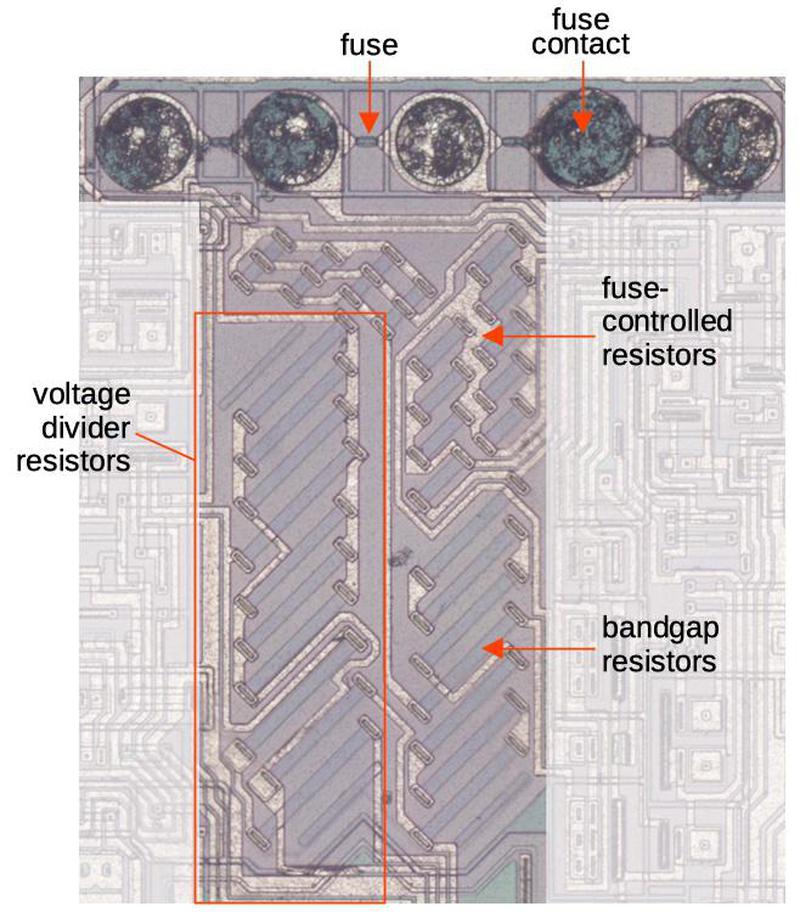

As mentioned earlier, resistors inside an IC are inaccurate. This poses a problem for the oscillator, since the discharge voltage level is set by resistors. The solution is to tune the resistances by putting fuses in parallel with small resistors and selectively blowing fuses to add the resistors to the circuit.4 Specifically, before the chip is packaged, its performance is measured. To blow a fuse, probes are pressed against the circular contacts and a large current is applied. The additional step of blowing fuses increases the manufacturing cost of the chip, but it provides more precise performance.

The oscillator has a second set of fuses to tune the discharge resistance (below). These fuses use a different principle: they are "antifuses", which act like fuses in reverse. An antifuse starts off non-conducting, but passing a high current through it creates a conductive metal spike in the antifuse.5

Current mirrors

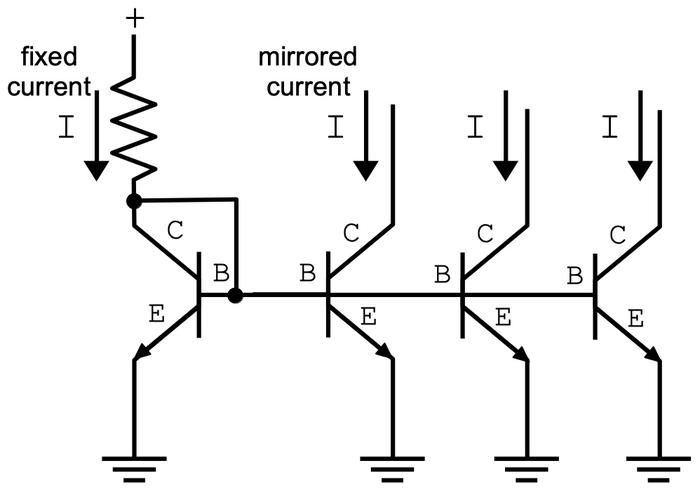

The current mirror is a fundamental building block in analog circuits. This chip, like many analog chips, needs small, steady currents to drive amplifiers, bias circuits, pull signals up, and perform other tasks. Rather than using separate resistors to generate each current, a common solution is the current mirror: you control one current with resistors, and then use transistors to make copies of this current. The schematic below shows a simple current mirror where the fixed current through the transistor on the left is mirrored into three identical copies.

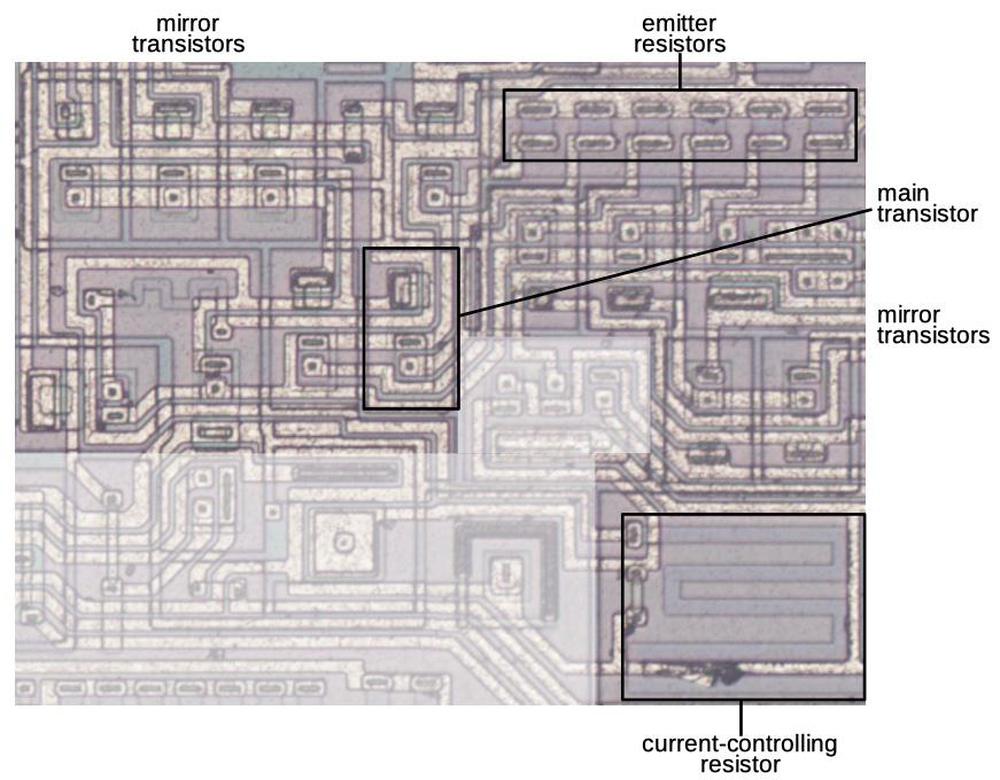

The diagram above shows the main current mirrors for the chip. The large resistor in the lower-right controls the current through the main transistor, and the other transistors copy this current.6 Small emitter resistors improve the performance.

The feedback or error amplifier

Next, I'll look at the voltage feedback circuit, which lets the chip know if the output voltage is too high or too low. The chip receives the output voltage, scaled to form a feedback signal. The error amplifier compares the feedback to a reference voltage to determine if the voltage is too high or too low.

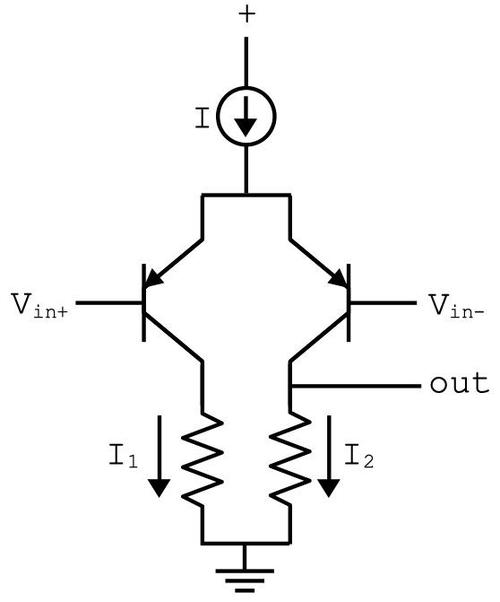

The error amplifier is based on a differential amplifier, which amplifies the difference between its two inputs. This circuit is common in analog circuits, forming the heart of an op-amp or a comparator. The basic idea is that a current mirror (the circle at the top) generates a fixed current I. This current gets split between the left path (I1) and the right path (I2). If the transistor on the left has a higher input voltage than the transistor on the right, most of the current will go to the left. But if the transistor on the right has a higher input, most of the current will go to the right. This circuit amplifies the voltage difference: even a small difference between the two inputs will switch most of the current from one side to the other.

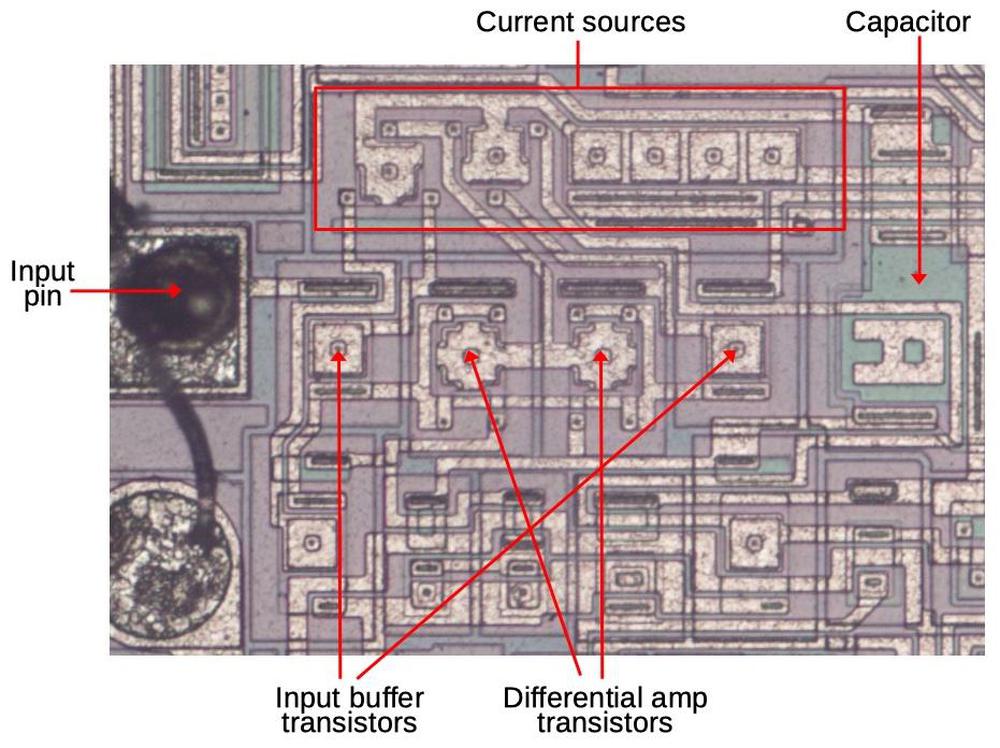

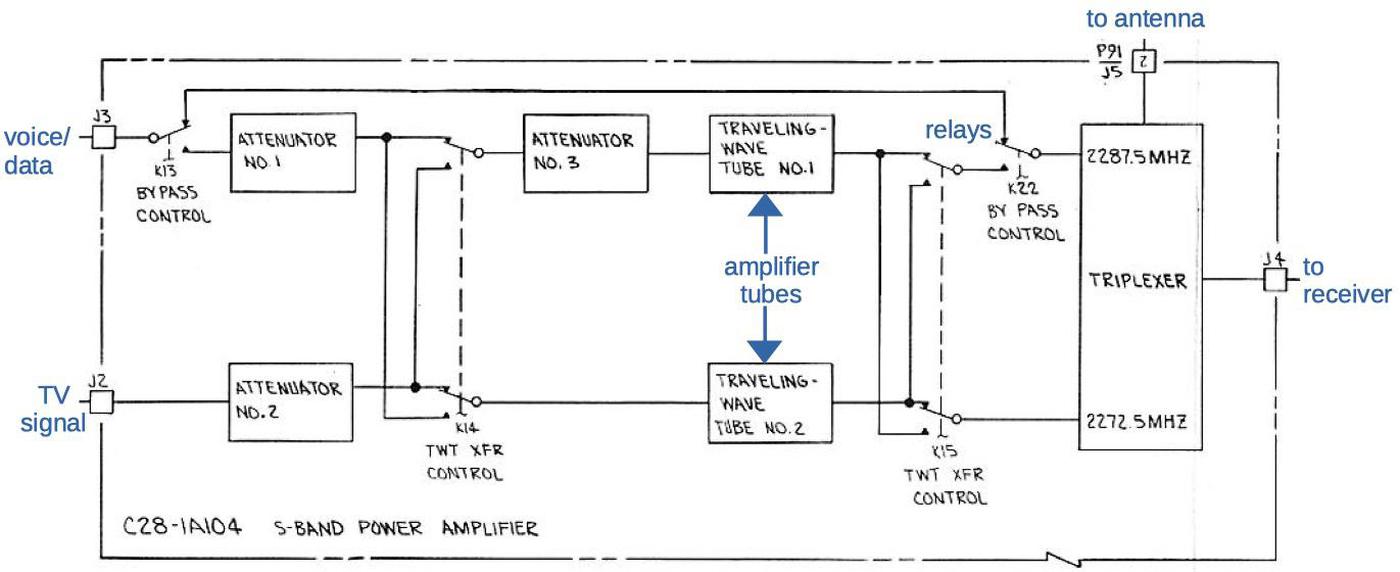

The error amplifier extends this circuit with about a dozen transistors in total. These transistors add buffering to the inputs, control various currents, and provide a second amplification stage. The photo below shows the key components of the error amplifier. The green capacitor on the right stabilizes the amplifier.

The current comparator

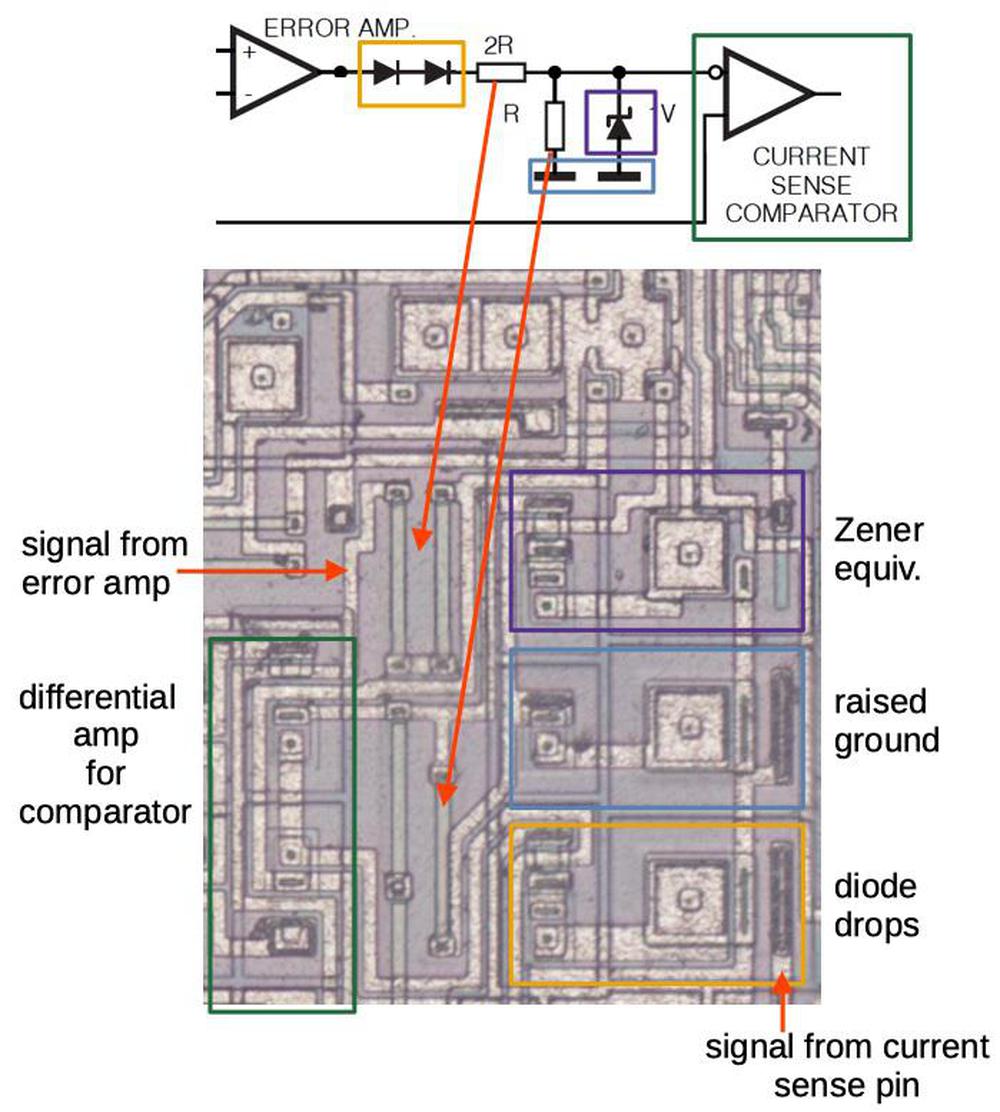

The power supply uses voltage feedback to adjust the pulse width, but it also monitors the current through the transformer so the power supply can respond faster to changes in the load. The current feedback is implemented by the "current sense comparator". This is similar to the feedback amplifier, amplifying the difference between the inputs. (Since it is a comparator, not an amplifier, it is designed to output a binary signal instead of an analog level, but the basic principle is the same.) The diagram below shows the key circuitry for the current comparator on the die and how it relates to the block diagram. The output from the error amplifier goes through some circuitry to adjust the voltage levels before entering the comparator.7

Under-voltage lockout

Another interesting circuit is the under-voltage lockout (UVLO), in the upper-left of the die. The purpose of this circuit is to shut down the chip cleanly if the input voltage falls too low. (This could happen if there is a power failure or even from unplugging the power supply.)

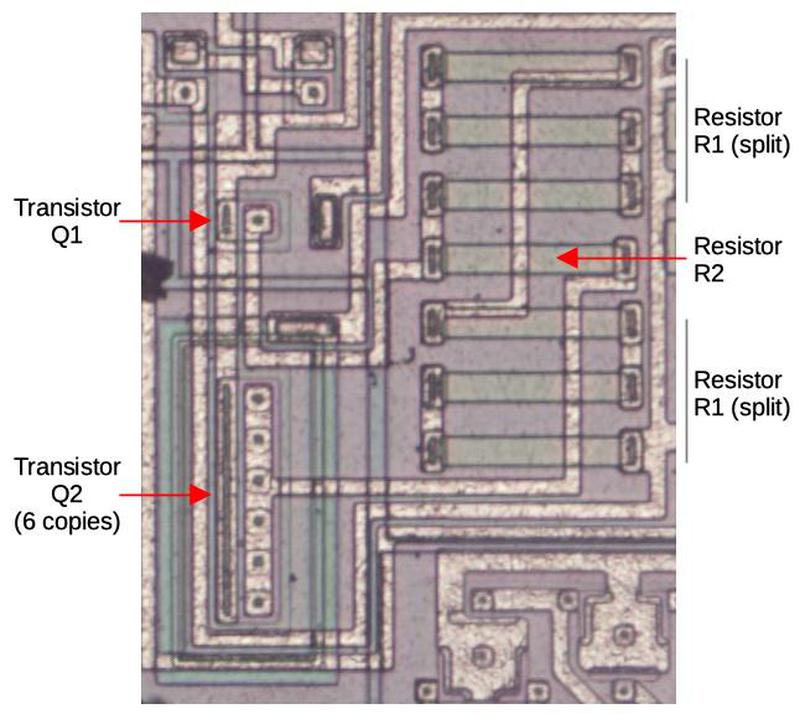

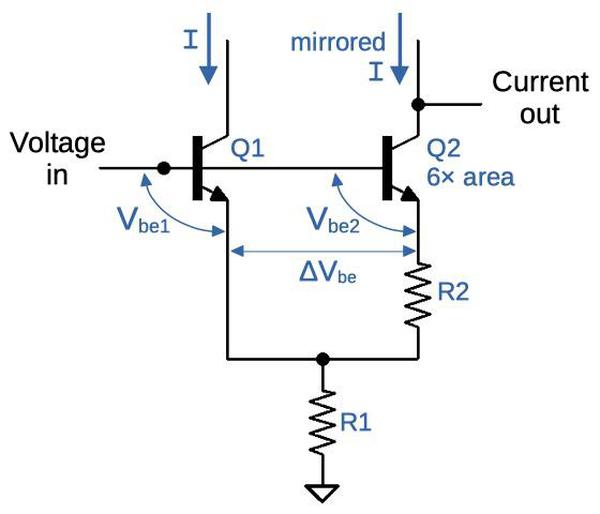

The heart of the UVLO circuit is a bandgap regulator, which provides a voltage reference that will be stable even if the temperature changes. This is surprisingly difficult in an integrated circuit, since the properties of transistors change with temperature. The bandgap regulator uses two transistors of different sizes so they are affected by temperature differently. In the die photo below, Q2 is six times the size of Q1.

The schematic below shows how the bandgap regulator is constructed. The key factor is the voltage between a transistor's base and its emitter (Vbe), which decreases with temperature. However, ΔVbe, the difference between the two Vbe increases with temperature. With the right resistors, these two factors cancel out, yielding a stable reference voltage. The circuit compares the input voltage to this reference voltage; see the footnote8 for more details.

In the UVLO circuit, the bandgap reference is used to detect if the chip's input voltage falls too low. Since the input voltage is around 30 volts, a network of resistors (below) scales it to the bandgap voltage (about 1.2 volts) for comparison.9

The bandgap voltage reference

The chip uses a second bandgap reference to create an internally-regulated 5 volt supply to power the chip's circuitry. This voltage is also made available to external circuitry that may need an accurate voltage.

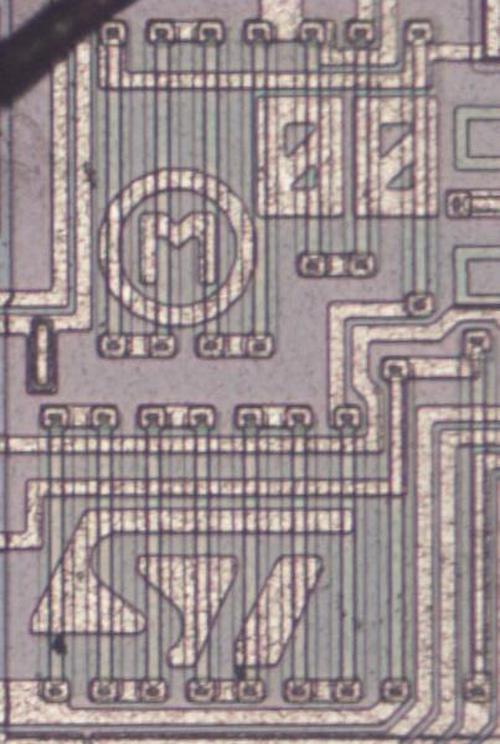

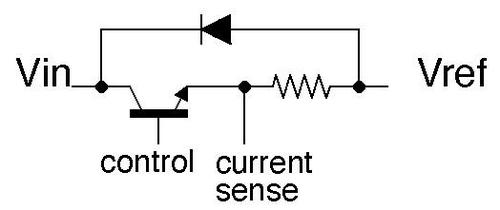

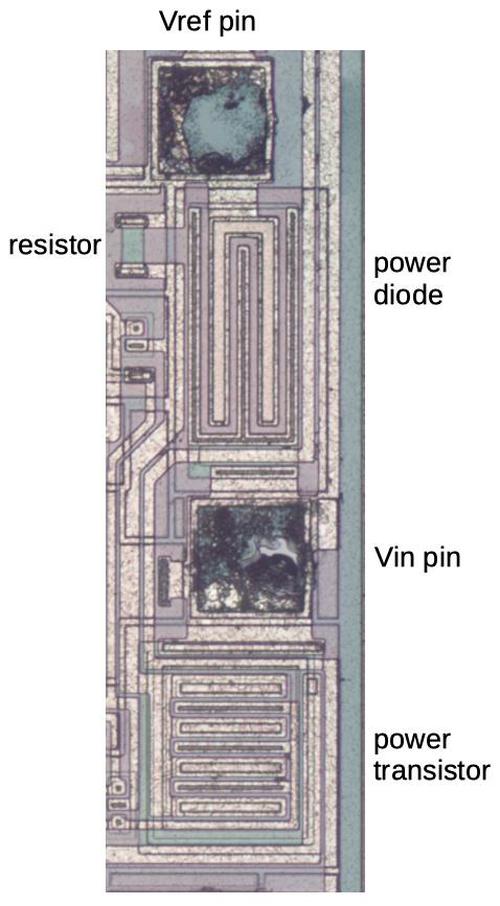

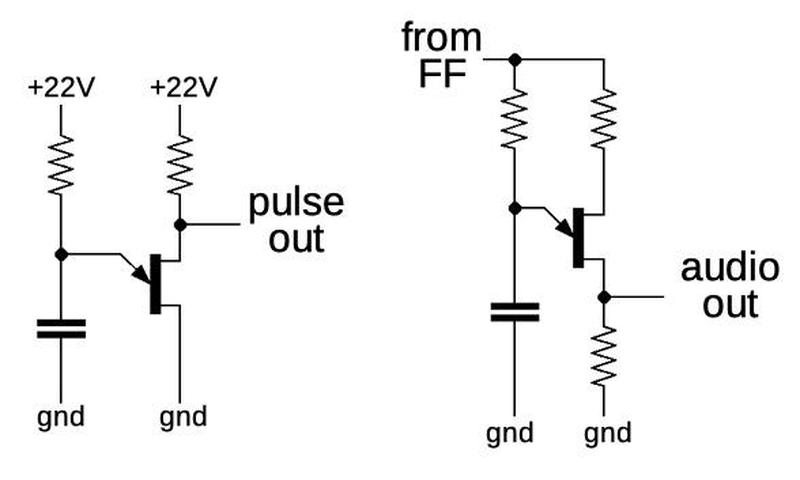

At a high level, this voltage reference is a linear power supply, with a power transistor controlling how much of the input voltage passes through to the regulated Vref. The control signal comes from the bandgap regulator, which I'll explain below. The output circuit also has a current-sense resistor to measure the output current. This limits the output current to 50 mA in case of a short circuit. A diode clamps the output if the input voltage suddenly drops.

The photo below shows how this circuit is implemented on the die. The power transistor is much larger than the other transistors, so it can support a high-current output. The construction of the diode is similar to the power transistor, but without a collector. The current-sense resistor is short and wide, giving it a low resistance.

The heart of the circuit is the bandgap voltage reference below. The circuit is similar to the bandgap voltage reference for the under-voltage lockout circuit, using two transistors, one with six times the area of the other. However, the six-way transistor has been split into two and surrounds the single transistor. With this layout, even if there is a temperature gradient across the die, the single-transistor and the six-transistor will be at the same average temperature.

The accuracy of the bandgap regulator depends on the accuracy of its resistors. During manufacturing, fuses are blown to tune the resistance, as with the oscillator's resistors. The photo below also shows the resistors that form a voltage divider to reduce the 5-volt output to the 1.2-volt bandgap voltage. In contrast to the thin meandering resistors used elsewhere, these resistors are thick and uniform length to improve their accuracy.

Output

At this point, I'll step back and review the chip's function in the power supply. It controls the switching transistor, causing the transistor to send high-voltage pulses through the transformer. The chip does this by producing control pulses on its output pin. Since the switching transistor is fairly large, the chip outputs a relatively high current (200 milliamps) control signal. This requires fairly large output transistors inside the IC.

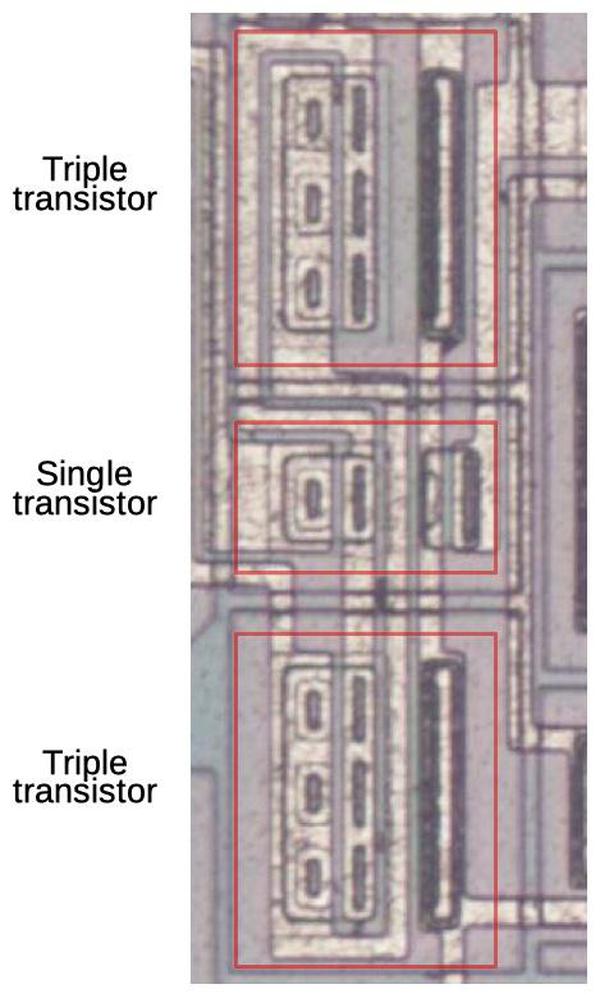

The die photo below shows the IC's two output transistors: the upper one pulls the output high, and the lower one pulls the output to ground. One interesting feature of the chip is that it has two pads on the die for Vin and two pads for ground. The purpose of this is that the output transistors draw a lot of current, which could cause noise fluctuations on the power and ground lines, interfering with the rest of the chip. By providing separate pads, the output transistor is somewhat isolated from the rest of the circuitry.10

Variants

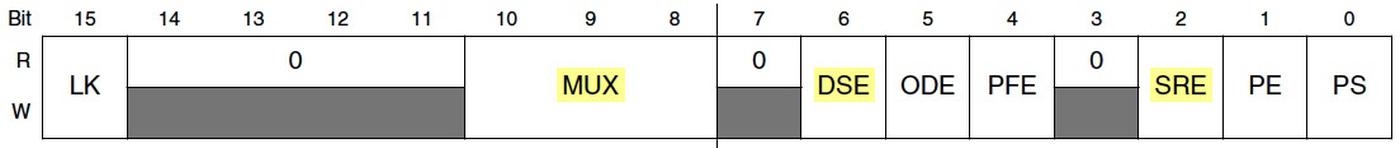

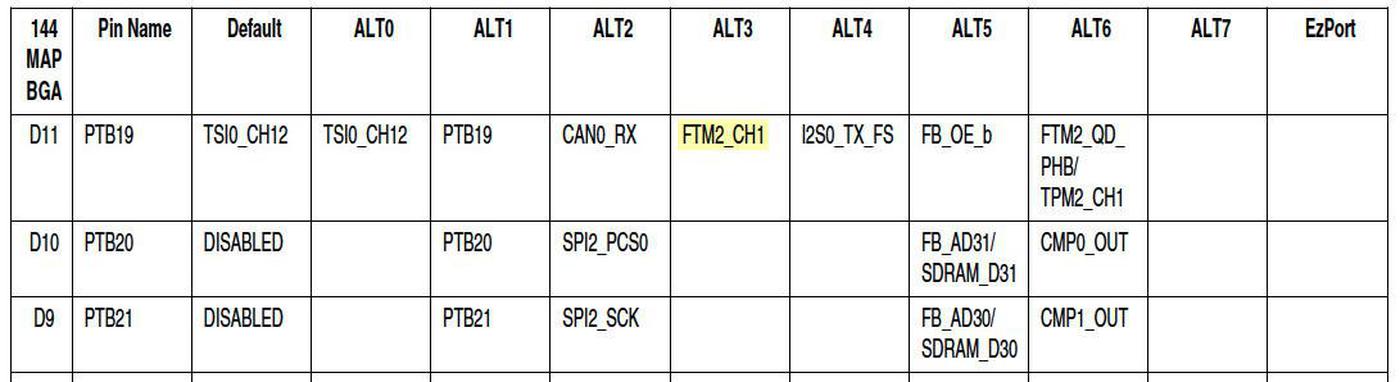

One interesting thing about this chip is that four different chips are manufactured from the same silicon. The UC3842 has a 16-volt UVLO threshold, while the UC3843 has an 8.5-volt threshold for lower-voltage applications. Other variants of the chip (UC3844 and UC3845) have a flip flop to reduce the pulse duty cycle. These different chips use slightly different metal wiring over the same silicon base. (It's easier to customize the metal layer than the silicon.) The photo below shows some places where the metal wiring has been severed in the UC3842 to change the wiring.

Conclusion

Power supplies are usually taken for granted, but they contain a lot of interesting technology. The invention of the power supply control chip in 1975 is a key step in the history of power supply improvements. Modern power supply chips are much more complex, with features to improve efficiency and reduce interference, but the chip that I examined uses the same basic principles.11 Analog chips are built from several important building blocks such as differential amplifiers, current sources, current mirrors, and bandgap voltage references. The UC3842 chip illustrates all of these building blocks, and how they are combined to build complex circuits.

I announce my latest blog posts on Twitter, so follow me at kenshirriff. I also have an RSS feed.

Notes and references

-

For schematics of power supplies using this UC3842 chip, see this site, near the bottom of the page. ↩

-

The idea of a Zener diode is that it blocks current like a normal diode until it reaches the "breakdown voltage", where it starts conducting. Zener diodes are often formed on chips from the emitter-base junction of NPN transistors, which commonly results in a 6.8-volt breakdown voltage. Looking at the photo, you can see 5 transistor-like structures in series. At 6.8 volts each, this generates the 34-volt breakdown voltage shown in the block diagram. ↩

-

The oscillator's comparator is set to turn off about 1.6 volts below the level at which it turns on, that is it has hysteresis. This ensures that the capacitor discharges significantly rather than settling around the discharge level. The oscillator design is a bit like the 555 timer, with discharge and charge phases triggered by the capacitor voltage. ↩

-

Many of the resistors in the fuse network are made of fixed-length resistors in various combinations. For example, two in parallel gives twice the resistance, while two in series give half the resistance. The advantage of combining fixed-length resistors is that the resistances are more predictable than making resistors of different lengths. The different resistors have roughly binary values, so different combinations of blown fuses select a variety of resistances. ↩

-

I think that the chip uses Zener antifuses, since they look similar to NPN transistors without a collector. The process of blowing the antifuse to make it conductive is called a "Zener zap." ↩

-

The current mirror uses a buffered-feedback design with emitter degeneration resistors (details). The small emitter resistors improve the output impedance. Three of the transistors in the current mirror are set up to split current, so each sinks one-third of the regular current. Another transistor has a larger emitter resistor, reducing the current; a small change in resistance yields a large change in the current. This illustrates the flexibility of a current mirror to produce different currents. ↩

-

The block diagram shows a resistor-diode network between the error amplifier and the current sense comparator. This network scales and clips the error amplifier output to make its levels more useful. The circuitry isn't particularly interesting, so I won't discuss it in detail. I'll mention, though, that the block diagram shows the error amplifier output uses two diodes to drop its voltage. The circuit, on the other hand, raises the other signals by two diode levels instead, which works out the same mathematically. (Transistors are used to implement the diode drops as well as the 1-volt Zener.) ↩

-

The details of a bandgap reference are too complex to explain here, but I'll give a brief overview in this footnote. The basis is that the voltage between a transistor's base and emitter scales drops linearly with the temperature (in Kelvin). But since the two transistors have different areas, the two transistors have different scale factors. The difference between the two transistors' base-emitter voltages increases linearly with temperature. By combining a voltage that decreases linearly with temperature and a voltage that increases linearly with temperature, you can create a voltage that remains almost constant with temperature. This voltage turns out to be the bandgap voltage of silicon, about 1.2 volts.

Scaling and combining these voltages is done by two resistors, so it is important that temperature doesn't affect the resistances. The circuit is designed so that only the ratio between resistances matters, so if temperature affects both resistors equally, the circuit is unaffected. A problem is that a temperature gradient on the chip could affect some resistors more than others, but the chip uses a clever layout technique to avoid this. There are seven resistor segments: one forms a resistor and six are in series to form a resistor with six times the resistance. The one-unit resistor is put in the middle with three segments above and three segments below. If a temperature gradient, for instance, increases the upper resistances, the resistor in the middle will have an "average" increase, while the 6-unit resistor will have three resistor segments with a large increase and three with a small increase, which will cancel out.

The bandgap circuit doesn't explicitly generate a 1.2-volt output. Instead, it implicitly compares the input voltage with 1.2 volts. The circuit is set up so a 1.2-volt input balances the currents through both transistors. If the voltage increases, the single transistor passes more current than the six-unit transistor. A current mirror forces each side of the circuit to have the same current, with the result that the "extra" current flows through the output. Thus, if the input voltage is high enough, the circuit produces an output current, activating the chip. But if the input voltage is too low, the circuit doesn't produce an output current, shutting down the chip.

For more information, see the optimistically-titled How to make a bandgap voltage reference in one easy lesson. ↩

-

Another feature of the under-voltage lockout circuit is hysteresis; it has a higher voltage to turn on than to shut off. The purpose of this is to make sure the power supply doesn't oscillate on and off if the input voltage is near the threshold. Hysteresis is implemented through the input voltage divider, which uses three resistors. If the chip is activated, a transistor feeds the supply voltage into the second resistor, increasing the divider's output voltage. The result is that once the chip is active, the supply voltage must drop more to turn the chip off. ↩

-

Surprisingly, the chip has two pads for power and two pads for ground, but only single power and ground pins. Instead, two bond wires go from the pads to each external power and ground pin. Although this doesn't provide complete separation between the chip's power and the output circuit's power, it is still beneficial since the bond wires are thicker than the metal traces and have lower resistance.

Although this IC is usually packaged in an 8-pin package, some manufacturers, such as Fairchild, make versions of the UC3842 in 14-pin packages. The extra pins allow separate pins to be used for the circuitry and output power and grounds. ↩

-

While the UC3842 chip was introduced in 1984, the one I examined has a mask date of "00", so this design is from 2000. The power supply itself was from 2005. ↩