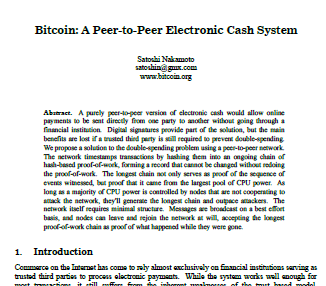

This article explains Bitcoin mining in details, right down to the hex data and network traffic.

If you've ever wondered what really happens in Bitcoin mining, you've come to the right place.

My previous article,

Bitcoins the hard way described how I manually created a Bitcoin transaction and sent it into the system. In this article, I show what happens next: how a transaction gets mined into a block.

The purpose of mining

Bitcoin mining is often thought of as the way to create new bitcoins. But that's really just a secondary purpose.

The primary importance of mining is to ensure that all participants have a consistent view of the Bitcoin data.

Because Bitcoin is a distributed peer-to-peer system, there is no central database that keeps track of who owns bitcoins. Instead, the log of all transactions is distributed across the network.

The main problem with a distributed transaction log is how to avoid inconsistencies that could allow someone to spend the same bitcoins twice.

The solution in Bitcoin is to mine the outstanding transactions into a block of transactions approximately every 10 minutes, which makes them official. Conflicting or invalid transactions aren't allowed into a block, so the double spend problem is avoided.

Although mining transactions into blocks avoid double-spending, it raises new problems: What stops people from randomly mining blocks? How do you decide who gets to mine a block? How does the network agree on which blocks are valid?

Solving those problems is the key innovation of Bitcoin:

mining is made very, very difficult, a technique called proof-of-work.

It takes an insanely huge amount of computational effort to mine a block, but it is easy for peers on the network to verify that a block has been successfully mined.[1]

Each mined block references the previous block, forming an unbroken chain back to the first Bitcoin block. This blockchain ensures that everyone agrees on the transaction record. It also ensures that nobody can tamper with blocks in the chain since re-mining all the following blocks would be computationally infeasible.[2]

As long as nobody has more than half the computational resources, mining remains competitive and nobody can control the blockchain.

As a side-effect, mining adds new bitcoins to the system. For each block mined, miners currently get 25 new bitcoins (currently worth about $15,000), which encourages miners to do the hard work of mining blocks. With the possibility of receiving $15,000 every 10 minutes, there is a lot of money in mining.

How mining works

Mining requires a task that is very difficult to perform, but easy to verify.

Bitcoin mining uses cryptography, with a hash function called

double SHA-256. A hash takes a chunk of data as input and shrinks it down into a smaller hash value (in this case 256 bits). With a cryptographic hash, there's no way to get a hash value you want without trying a whole lot of inputs. But once you find an input that gives the value you want, it's easy for anyone to verify the hash. Thus, cryptographic hashing becomes a good way to implement the Bitcoin "proof-of-work".

In more detail, to mine a block, you first collect the new transactions into a block. Then you hash the block to form a 256-bit block hash value. If the hash starts with enough zeros[3], the block has been successfully mined and is sent into the Bitcoin network and the hash becomes the identifier for the block.

Most of the time the hash isn't successful, so you modify the block slightly and try again, over and over billions of times. About every 10 minutes someone will successfully mine a block, and the process starts over.

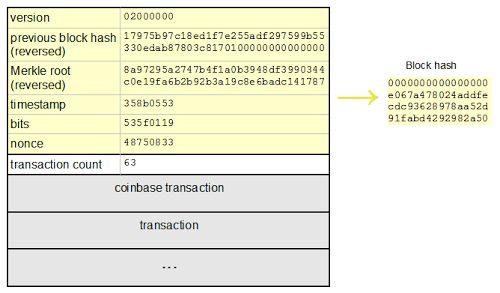

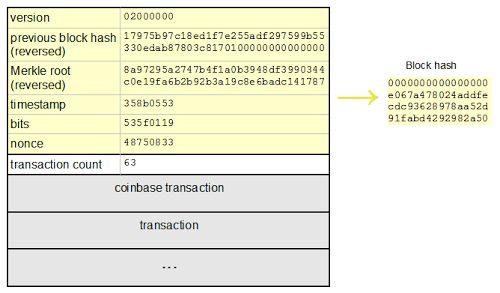

The diagram below shows the structure of a specific block, and how it is hashed. The yellow part is the block header, and it is followed by the transactions that go into the block. The first transaction is the special coinbase transaction that grants the mining reward to the miner. The remaining transactions are standard Bitcoin transactions moving bitcoins around.

If the hash of the header starts with enough zeros[3], the block is successfully mined. For the block below, the hash is successful: 0000000000000000e067a478024addfecdc93628978aa52d91fabd4292982a50 and the block became block

#286819 in the blockchain.

Structure of a Bitcoin block

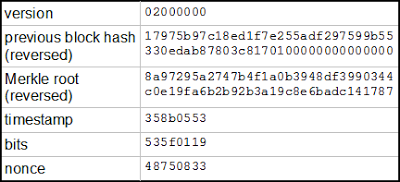

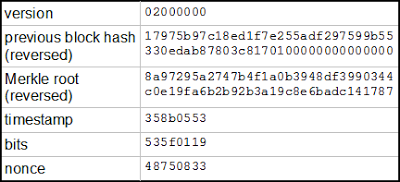

The block header contains a handful of fields that describe the block.

The first field in the block is the protocol version. It is followed by the hash of the previous block in the blockchain, which ensures all the blocks form an unbroken sequence in the blockchain. (Inconveniently, the hash is reversed in the header.)

The next field is the Merkle root,[4] a special hash of all the transactions in the block. This is also a key part of Bitcoin security, since it ensures that transactions cannot be changed once they are part of a block.[5]

Next is a (moderately accurate) timestamp of the block, followed by the mining difficulty value bits.[3]

Finally, the nonce is an arbitrary value that is incremented on each hash attempt to provide a new hash value. The tricky part of mining is finding a nonce that works.

ASIC Bitcoin Miner

Photo by Mirko Tobias Schaefer,

(CC BY 2.0)

A short program to mine a block

I wrote a Python program that mines the above block. The program itself is pretty simple - the hardest part of the code is computing the difficulty target from

bits.

[3] Otherwise it's just a loop over different nonce values. Each iteration puts the data into a structure, hashes it, and tests the result.

The following table shows the hash obtained for selected nonce values. The key point is that each nonce generates a basically-random hash value. Every so often a "lucky" nonce will generate a hash starting with some zeroes. To get a lot of zeroes, you need to try an exponentially large number of nonces. For this block, the "winning" nonce is 856192328.

| nonce | hash |

|---|

| 0 | 5c56c2883435b38aeba0e69fb2e0e3db3b22448d3e17b903d774dd5650796f76 |

| 1 | 28902a23a194dee94141d1b70102accd85fc2c1ead0901ba0e41ade90d38a08e |

| 2 | 729577af82250aaf9e44f70a72814cf56c16d430a878bf52fdaceeb7b4bd37f4 |

| 3 | 8491452381016cf80562ff489e492e00331de3553178c73c5169574000f1ed1c |

| 39 | 03fd5ff1048668cd3cde4f3fb5bde1ff306d26a4630f420c78df1e504e24f3c7 |

| 990 | 0001e3a4583f4c6d81251e8d9901dbe0df74d7144300d7c03cab15eca04bd4bb |

| 52117 | 0000642411733cd63264d3bedc046a5364ff3c77d2b37ca298ad8f1b5a9f05ba |

| 1813152 | 00000c94a85b5c06c9b06ace1ba7c7f759e795715f399c9c1b1b7f5d387a319f |

| 19745650 | 000000cdccf49f13f5c3f14a2c12a56ae60e900c5e65bfe1cc24f038f0668a6c |

| 243989801 | 0000000ce99e2a00633ca958a16e17f30085a54f04667a5492db49bcae15d190 |

| 856192328 | 0000000000000000e067a478024addfecdc93628978aa52d91fabd4292982a50 |

I should point out that I cheated by starting with a block that could be successfully mined.

Most of the attempts to mine a block will fail entirely - none of the nonce values will succeed. In that case, you need to modify the block slightly and try again. The timestamp can be adjusted (which is why the timestamp in mined blocks is often wrong). New transactions can be added to the block, changing the Merkle hash. The coinbase transaction can be modified - this turns out to be very important for mining pools. Any of these changes will result in totally different hashes, so the nonce values can be tried again.

My Python program does about 42,000 hashes per second, which is a million times slower than the hardware used by real miners. My program would take about 11 million years on average to mine a block from scratch.

Mining is very hard

The difficulty of mining a block is astounding. At the

current difficulty, the chance of a hash succeeding is a bit less than one in 10

19.

Finding a successful hash is harder than finding a particular grain of sand from all the

grains of sand on Earth.

To find a hash every ten minutes, the Bitcoin hash rate needs to be insanely large.

Currently, the

miners on the Bitcoin network are doing about 25 million gigahashes per second. That is, every second about 25,000,000,000,000,000 blocks gets hashed. I estimate (very roughly) that the total hardware used for Bitcoin mining cost tens of millions of dollars and uses as much power as the country of Cambodia.

[6]

Note that finding a successful hash is an entirely arbitrary task that doesn't accomplish anything useful in itself. The only purpose of finding a small hash is to make mining difficult, which is fundamental to Bitcoin security. It seems to me that the effort put into Bitcoin mining has gone off the rails recently.

Mining is funded mostly by the 25 bitcoin reward per block, and slightly by the transaction fees (about 0.1 bitcoin per block). Since the mining reward currently works out to about $15,000 per block, that pays for a lot of hardware. Per transaction, miners are getting about $34 in mining reward and $0.10 in fees (stats).

15 GH/s FPGA Bitcoin mining configuration with 41 Icarus. Photo by permission of Xiangfu Liu

Mining with a pool

Because mining is so difficult, it is typically done in mining pools,

where a bunch of miners share the work and share the rewards. If you mine by yourself, you might successfully mine a block and get 25 bitcoin every few years. By mining as part of a pool, you could get a fraction of a bitcoin every day instead, which for most people is preferable.

Mining pools use an interesting technique to see how much work miners are doing. They send out a block to be mined, and get updates from a miner whenever a miner gets a partial solution. Each partial solution proves the miner is working hard on the problem and gives the miner a share in the final reward when someone succeeds in mining the block.

For instance, if Bitcoin mining requires a hash starting with 15 zeroes, the mining pool can ask for hashes starting with 10 zeroes, which is a million times easier. Depending on the power of their hardware, a miner might find such a solution every few seconds or a few times an hour. Eventually one of these solutions will start with not just 10 zeroes but 15 zeroes, successfully mining the block and winning the reward for the pool.[7] The reward is then split based on each miner's count of shares as a fraction of the total, and the pool operator takes a small percentage for overhead.[8]

Most of the time someone outside the pool will mine a block first. In that case, the pool operator sends out new data and the miners just start mining the new block. People in a pool can get edgy if a long time goes without a payout because of bad luck in mining.

Stratum: The communication between a pool and the miners

Next I'll look in detail at the communication between a miner and the mining pool.

The communication between the pool and the miners is interesting.

The pool must efficiently provide work to the miners and collect their results quickly. The pool must make sure miners aren't duplicating work. And the pool must make sure miners don't waste time working on a block that has already been mined.

An important issue for mining pools is how to support fast miners. The nonce field in the header is too small for fast miners since they will run through all the possible values faster than the pool can send blocks. The solution is to allow miners to update the coinbase transaction so they can put additional nonces there. This makes mining more complicated since after building the coinbase transaction the miner must recompute the Merkle hash tree and then try mining the block.

I'm going to look at the Stratum mining pool protocol that is used by many pools.

(Some alternative protocols are the Getwork and Getblocktemplate protocols.)

The following Python program uses the Stratum protocol to make a mining request to the GHash.IO mining pool and displays the results. (This program is a minimal demonstration; don't use this code for real mining.)

The information below is what the mining pool sends back over the network in response to the program above. Since the Stratum protocol uses

JSON-RPC

the results are readable ASCII rather than the binary packets used by most of Bitcoin.

This provides all the data needed to start mining as part of the pool:

{"id":1,"result":[[["mining.set_difficulty","b4b6693b72a50c7116db18d6497cac52"],["mining.notify","ae6812eb4cd7735a302a8a9dd95cf71f"]],"4bc6af58",4],"error":null}

{"id":null,"params":[16],"method":"mining.set_difficulty"}

{"id":null,"params":["58af8d8c","975b9717f7d18ec1f2ad55e2559b5997b8da0e3317c803780000000100000000","01000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000ffffffff4803636004062f503253482f04428b055308","2e522cfabe6d6da0bd01f57abe963d25879583eea5ea6f08f83e3327eba9806b14119718cbb1cf04000000000000000000000001fb673495000000001976a91480ad90d403581fa3bf46086a91b2d9d4125db6c188ac00000000",["ea9da84d55ebf07f47def6b9b35ab30fc18b6e980fc618f262724388f2e9c591","f8578e6b5900de614aabe563c9622a8f514e11d368caa78890ac2ed615a2300c","1632f2b53febb0a999784c4feb1655144793c4e662226aff64b71c6837430791","ad4328979dba3e30f11c2d94445731f461a25842523fcbfa53cd42b585e63fcd","a904a9a41d1c8f9e860ba2b07ba13187b41aa7246f341489a730c6dc6fb42701","dd7e026ac1fff0feac6bed6872b6964f5ea00bd8913a956e6b2eb7e22363dc5c","2c3b18d8edff29c013394c28888c6b50ed8733760a3d4d9082c3f1f5a43afa64"],"00000002","19015f53","53058b41",false],"method":"mining.notify"

{"id":2,"result":true,"error":null}

{"id":null,"params":[16],"method":"mining.set_difficulty"}

The first line is a response from the pool server with the subscription details. The first values are not too important. The value

4bc6af58 is the value

extranonce1 that is used when building the block. Each client gets a unique value to ensure that all the mining clients generate unique blocks and don't duplicate work. The following value (

4 bytes) is the length of the

extranonce2_size value that the miner puts in the coinbase while mining.

The second line is a mining.set_difficulty message to our client. With a difficulty of 16, I can get a share every hour or two on my PC.

In comparison, the Bitcoin mining difficulty is 3,129,573,174.52[3] - thus it's about 200 million times easier to get a share in this pool than to successfully mine a block independently. That's why people join pools.

The third line is a mining.notify notification to our client. This message defines that block for us to mine. There's a lot of data returned under "params", so I'll explain it field by field.

| job_id | 58af8d8c |

| prevhash | 975b9717f7d18ec1f2ad55e2559b5997b8da0e3317c803780000000100000000 |

| coinb1 | 0100000001000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

0000000000ffffffff4803636004062f503253482f04428b055308 |

| coinb2 | 2e522cfabe6d6da0bd01f57abe963d25879583eea5ea6f08f83e3327eba9806b

14119718cbb1cf04000000000000000000000001fb673495000000001976a914

80ad90d403581fa3bf46086a91b2d9d4125db6c188ac00000000 |

| merkle_branch | ["ea9da84d55ebf07f47def6b9b35ab30fc18b6e980fc618f262724388f2e9c591", ...] |

| version | 00000002 |

| nbits | 19015f53 |

| ntime | 53058b41 |

| clean_jobs | false |

The job_id is used to identify this mining task if the miner reports back success.

Most of the fields are used in the block header. The prevhash is the hash of the previous block. Apparently mixing big-ending and little-endian isn't confusing enough so this hash value also has every block of 4 bytes reversed. The version is the block protocol version. The nbits indicates the difficulty[3] of the block. The timestamp ntime is not necessarily accurate.

The coinb1 and coinb2 fields allow the miner to build the coinbase transaction for the block. This transaction is formed by concatenating coinb1, the extranonce1 value obtained at the start, the extranonce2 that the miner has generated, and coinb2. The result is a transaction in Bitcoin protocol. The merkle_branch hash list lets the miner efficiently recompute the Merkle hash with the new coinbase transaction.

clean_jobs is used if the miner needs to restart the mining jobs.

After receiving this data, the miner can start generating coinbase transactions and mining blocks.

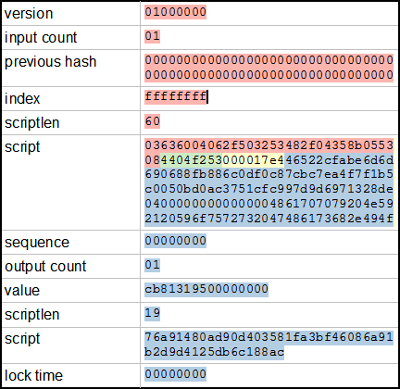

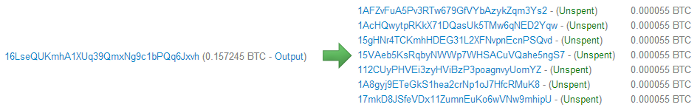

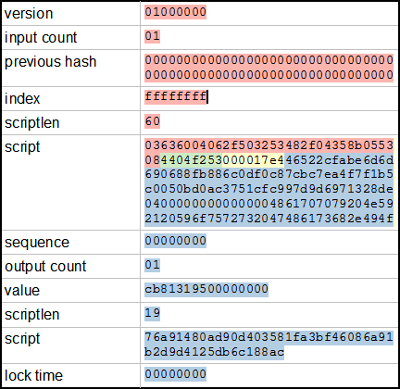

Creating a block for a pool

Once the miner has received the information from the pool, it is straightforward to form the coinbase transaction by joining the

coinb1,

extranonce1,

extranonce2, and

coinb2 to form a coinbase transaction. The diagram below shows how the combination of these four values forms a complete transaction, with the nonces in the middle of the coinbase script. (The block below is slightly different from the one described earlier.)

A coinbase transaction generated by the GHash.io mining pool

The structure of the coinbase transaction is similar to a regular transaction, but there are a few important differences. A normal transaction transfers bitcoins from inputs (usually source addresses) to outputs (usually destination addresses). A coinbase transaction is generating new bitcoins out of thin air, rather than doing a transfer, so the transaction is slightly different. The previous output hash and index are irrelevant for the coinbase transaction. the first script is the scriptSig which signs the transaction to prove ownership of the incoming bitcoins. In a coinbase transaction, this is irrelevant, so instead the field is called the coinbase and is mostly arbitrary data.[9] (Many miners hide messages in there.) The value field in the coinbase transaction is the 25 bitcoin mining reward plus any bitcoins left over from the other transactions (the left over bitcoins are treated as mining fees). Finally, both regular transactions and the coinbase transaction use the second script (scriptPubKey) to specify the recipients of the bitcoins.[10]

For details on transactions, see my my previous article.

Once the coinbase transaction is created, the hash for this coinbase transaction is combined with the merkle_branch data from the pool to generate the Merkle hash[4] for the entire set of transactions. Because of the structure of the Merkle hash (explained below), this allows the hash for the entire set of transactions to be recomputed easily.

Finally, the block header is built from the new Merkle hash and the data provided by the pool, and the hash algorithm can iterate over the nonce values in the header, just like the Python program earlier. Once all the nonce values have been tried, the miner increments the extranonce2, generates a new coinbase transaction and continues.

A Bitcoin block header

Informing the mining pool of success

The difficulty

[3] for a mining pool is set much lower than the Bitcoin mining difficulty (fewer leading zeros required), so it's much easier to get a share. When a block is hashed to the pool's difficulty, you send a simple JSON message to the mining pool to submit it:

{"method": "mining.submit", "params": ["kens.worker1", "58af8db7", "00000000", "53058d7b", "e8832204"], "id":4}

The parameters are the worker name, job id, extranonce2, time, and header nonce. This information is sufficient for the pool to build the matching coinbase transaction and header, and verify the block. If the hash meets the pool difficulty, you get a share. If the hash also meets the much, much harder Bitcoin difficulty, the block has been successfully mined. In this case the pool submits the block to the Bitcoin network and everyone with shares gets paid accordingly.

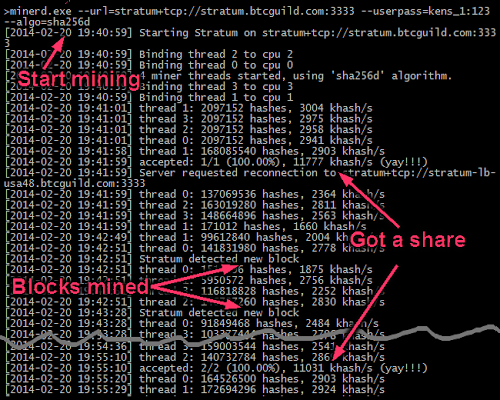

Mining for fun and profit

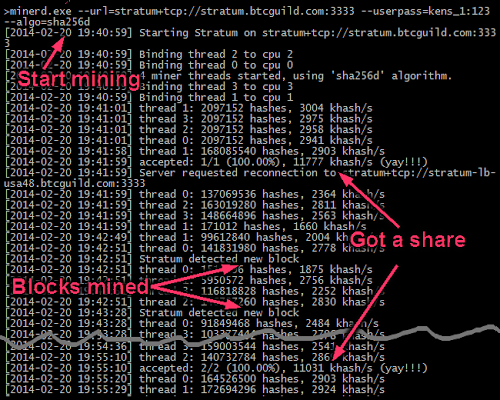

If you're curious about mining, it's surprisingly easy to try out mining yourself, although you'll be lucky to earn even a penny. Just create an account at a mining pool such as

BTC Guild, download mining software such as

cpuminer (minerd.exe), and run the software to start mining. For a pool with low difficulty, you should get shares in a few minutes; in a pool with a higher difficulty (such as GHash.IO), it may take you an hour or two to get a share, which is more frustrating.

[3]

Unprofitable Bitcoin CPU mining on my PC

The screenshot above shows what mining looks like as you get shares and blocks get mined. I got lucky and it only took me a minute to successfully mine a share. A minute later someone successfully mined a block, so the pool tells everyone to start over. Another block was mined less than a minute after that - although blocks are 10 minutes apart on average, the times can vary widely. It took 12 minutes for my next share to be generated. After running for a while, I earned 0.00000043 BTC, which is a tiny fraction of a cent.

Bitcoin mining is an "arms race". Originally people could mine with the CPU on a regular PC, but that hasn't been practical for a while. Next mining was offloaded to GPUs. Now, mining is done with special-purpose ASIC hardware, which is rapidly increasing in speed. For-profit mining is very competitive, and you'll need to look elsewhere for information.

If you want to try out mining just for fun, you may prefer to mine a currency such as Dogecoin rather than Bitcoin. First, Dogecoin uses a different hash algorithm which doesn't work well with ASIC hardware, so you're not as disadvantaged compared to professional miners.

Second, because dogecoins are worth much less than bitcoins, you'll end up with a much larger number of dogecoins, which seems more rewarding.

For Dogecoin mining, I used the dogepool.pw pool somewhat arbitrarily. The process is almost the same as Bitcoin mining, except you use the scrypt algorithm instead of sha256d.

There are many other alternative cryptocurrencies to choose from.

Notes and references

[1]

Bitcoin mining seems like a

NP (nondeterministic polynomial) problem since a solution can be quickly verified. However, there are a couple of issues with making this rigorous. First, since hashes are a fixed size, mining can be done in constant time (but with a very large constant of 2^256). Thus, you'd need to consider an extended mining scheme where the difficulty can go to infinity. Second, mining would need to be turned into a decision problem - e.g. instead of finding a nonce, the problem would be "Is there a successful nonce less than k". (Note that if you can solve that problem, you can rapidly find the nonce with binary search.)

With these changes, the mining problem is in NP.

The next question is if it is NP-complete. That is, can an arbitrary NP-complete problem be turned into a mining problem? I believe that is currently unknown.

[2]

You might wonder what happens if two miners succeed in mining a block at approximately the same time. Has the problem of conflicting transactions has just been replaced by the problem of conflicting blocks?) The rule is that only the longest chain

of valid blocks is used, and the other branch is ignored. Thus, when a miner extends the chain with one of the two parallel blocks, the other block becomes an orphan block and is ignored.

Orphan blocks are fairly common, roughly one a day.

For this reason, the (somewhat arbitrary) recommendation is to wait for six confirmations (about one hour) before considering a transaction solidly confirmed.

[3]

I've been describing a successful hash as starting with enough zeros, but there's an official definition of difficulty.

A valid block must have a hash below a target value. (Since the target starts with a bunch of zeros, so will the valid hash.)

There are two different hard-to-understand ways of representing the target.

The first, bits is a mantissa/exponent representation of the target in 32 bits.

The second, difficulty is the ratio between a base target and the current target.

A difficulty of N is N times as difficult as this base target.

The base target is 0x00000000FFFF0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000, which corresponds to approximately 1 in 232 or 1 in 4.2 billion hashes succeeding.

Difficulty changes approximately every two weeks to keep the block hash rate around 1 every 10 minutes. The https://blockchain.info/stats difficulty value is

3,129,573,174.52, corresponding to a target of 00000000000000015f5300000000000000000000000000000000000000000000.

Multiplying my PC's performance by the current difficulty shows it would take my PC about 35,000 years to mine a block.

The pool difficulty is important when using a mining pool.

My PC can do about 12 million hashes/sec running cpuminer, so at a difficulty of 1 my PC could find a block every 6 minutes. The BTC Guild pool uses a difficulty of 2, so I get a share about every 12 minutes. GHash.IO has a minimum difficulty of 16 on the other hand, so I only get a share every hour or two on the average. (My overall earnings would be similar either way, since the shares per block scale inversely with the difficulty.)

[4]

Instead of hashing all the transactions into the block directly, the transactions are first hashed together to yield a Merkle root. The Merkle root is the root of a binary Merkle tree. The idea is to start with all the transaction hashes. Pairs of hashes are hashed together to yield new hashes. The process is repeated on the new list of hashes and continues recursively until a single hash is obtained. This final root hash is the value used when computing the block. (See Wikipedia for more details.)

In the Merkle tree, each transaction is hashed. Then pairs of hashes are hashed together. Then pairs of the new hashes are hashed together, and so on, until a single hash remains. This allows the hash of a single transaction to be verified efficiently without recomputing all the hashes. One place this comes in useful is generating a new coinbase transaction for a mining pool.

The (patented) idea of a Merkle tree is if you need to modify or verify a single transaction, you don't need to recompute everything, but can just recompute the affected pairs. Personally, I think the Merkle tree is a pointless optimization for Bitcoin and for reasonable transaction numbers it would be faster to do a single large hash, rather than multiple hashes up the Merkle tree.

Here's some demonstration code to compute the Merkle root for the block I'm discussing. The 99 transaction hashes are hard-coded for convenience. The resulting Merkle root is 871714dcbae6c8193a2bb9b2a69fe1c0440399f38d94b3a0f1b447275a29978a

[5]

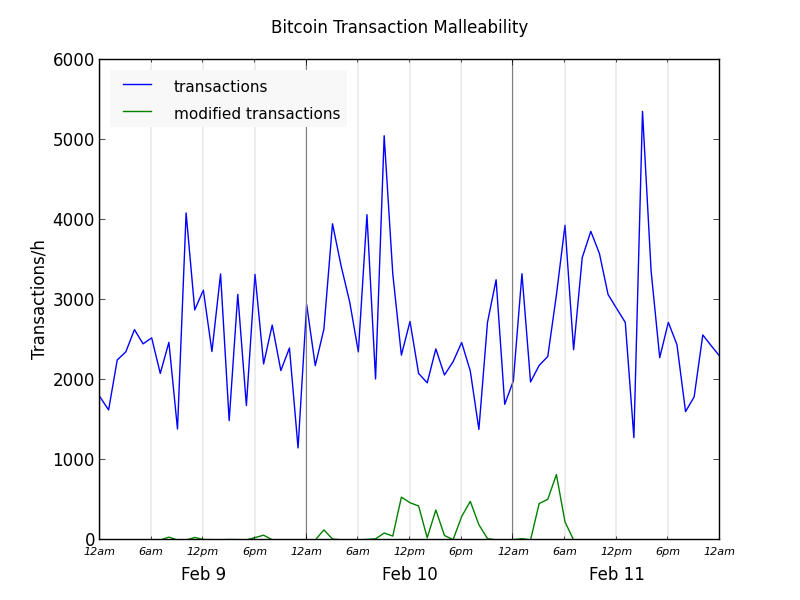

There are a few ways that third parties can modify transactions without invalidating the signature on the transaction. This is known as transaction malleability. These modifications change the hash of the transaction. Since the hash is part of the block, a transaction has a fixed hash and cannot be modified by malleability once it has been mined into a block. (Unless the whole block is orphaned, of course.)

[6]

It's hard to estimate the cost of mining because the hardware is changing so rapidly and it's unclear what is actually in use, but I'll do a rough calculation. Looking at the Bitcoin mining hardware and Mining hardware comparison pages, the HashBlaster looks like the most efficient currently available at 375 MH/s/$ and 1818 MH/s/W. The Bitcoin network is 25 billion MH/s, which works out to about $70 million hardware cost and 15 MW.

(This is about the total power consumption of Cambodia.)

At $0.15/kWH, that would be about $50,000/day on electricity ($300 per block or $0.70 per transaction).

Since mining generates about $140,000 per day, spending $50,000 per day on electricity seems like the right ballpark.

Other estimates are at Hacker News.

[7]

You might wonder why a miner doesn't cheat. If they successfully mine a block, why not submit it themselves so they can claim the full mining reward, rather than splitting it? The main reason is the coinbase transaction has the pool's address, not the miner's address. If the miner submits the block bypassing the pool, the reward still goes to the pool. And if the miner changes the address, the hash is no longer valid.

[8]

There are several different reward systems used by mining pools. For instance, a pool can pay out the exact amount earned from a block or an average amount. Or a pool can pay a fixed amount per share. A pool can weight shares by time to avoid miners switching between pools mid-block. These different systems can balance risk between the miners and the pool operator and adjust the variance of payments.

For details, see the Bitcoin wiki here or here.

[9]

I've figured out a lot of the structure of the coinbase script above.

First it contains the block height (0x046063 or 286819), which is

required for version 2). Next is the string '/P2SH/' which indicates the miner supports

Pay To Script Hash).

This is followed by a timestamp. Next is 8 bytes of the two nonces. This is followed by apparently-random data and then the text "Happy NY! Yours GHash.IO".

[10]

The typical coinbase script format has changed over time. Originally, the output scripts were all pay-to-pubkey, with the script: public_key OP_CHECKSIG. This script puts the public key itself in the script.

However, now about 95% of coinbase transactions use the standard pay-to-pubkey-hash script: OP_DUP OP_HASH160 addr OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG. This script only includes the public key hash (the address) and requires the redeemer to provide the public key.

To see the difference, compare the output scripts in

this transaction and

this transaction.