We recently started restoring a vintage1 analog computer. Unlike a digital computer that represents numbers with discrete binary values, an analog computer performs computations using physical, continuously changeable values such as voltages. Since the accuracy of the results depends on the accuracy of these voltages, a precision power supply is critical in an analog computer. This blog post discusses how this computer's power supply works, and how we fixed a problem with it. This is the second post in the series; the first post discussed the precision op amps in the computer.

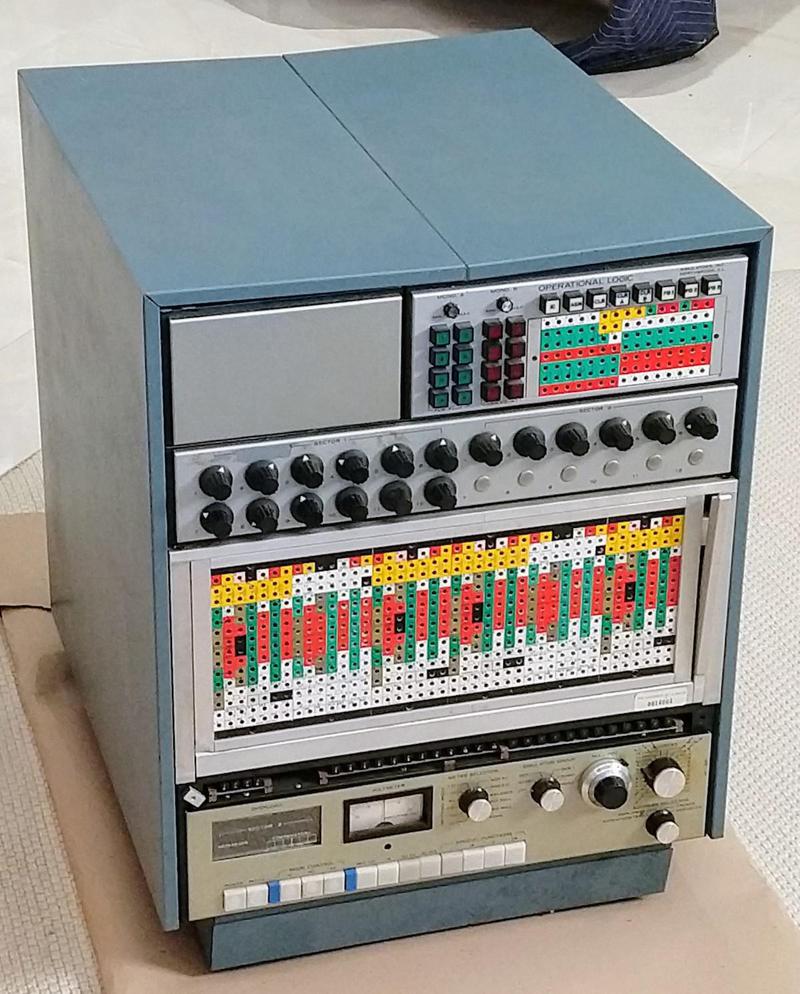

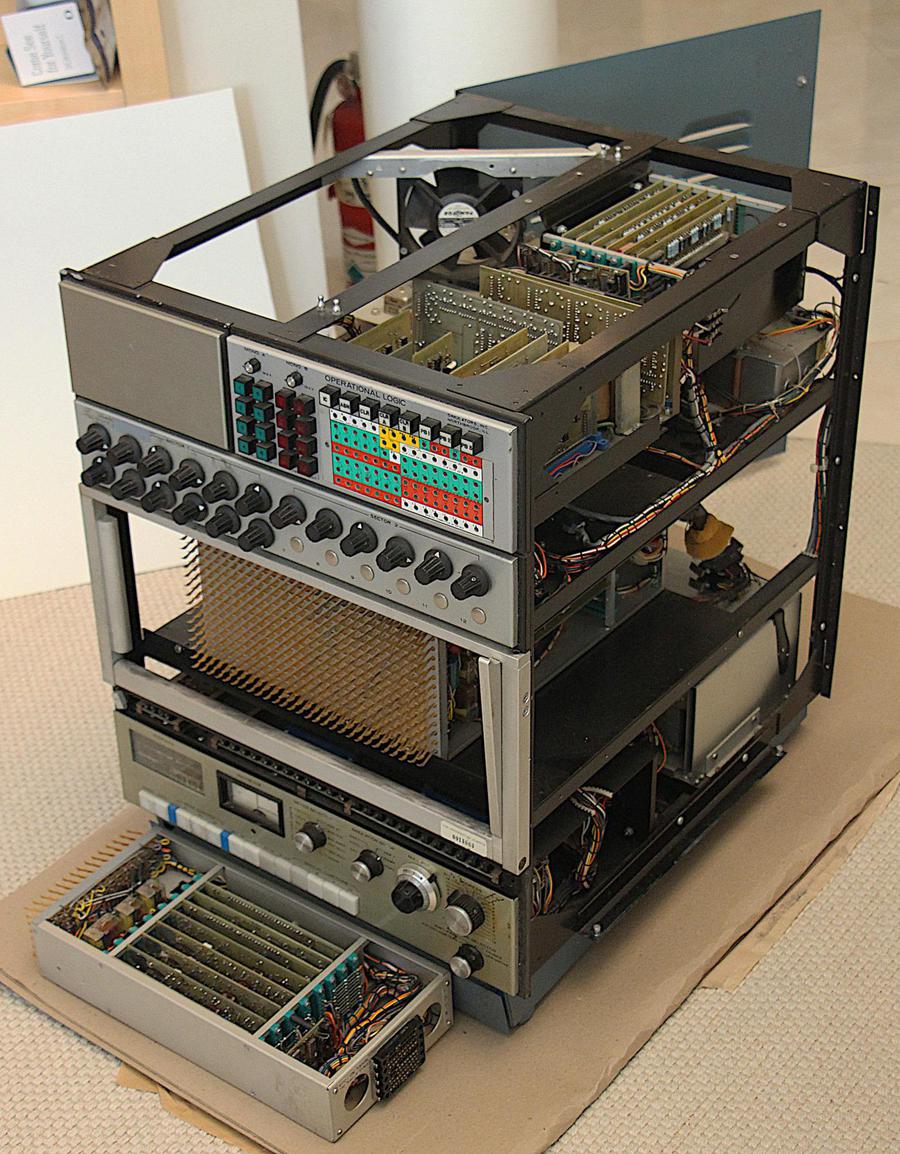

Analog computers used to be popular for fast scientific computation, especially differential equations, but pretty much died out in the 1970s as digital computers became more powerful. They were typically programmed by plugging cables into a patch panel, yielding a spaghetti-like tangle of wires. In the photo above, the colorful patch panel is in the middle. Above the patch panel, 18 potentiometers set voltage levels to input different parameters. A smaller patch panel for the digital logic is in the upper right.

The power supply

The computer uses two reference voltages: +10 V and -10 V, which the power supply must generate with high accuracy. (Older, tube-based analog computers typically used +/- 100 V references.) The power supply also provides regulated +/- 15 V to power the op amps, power for the various relays in the computer, and power for the lamps.

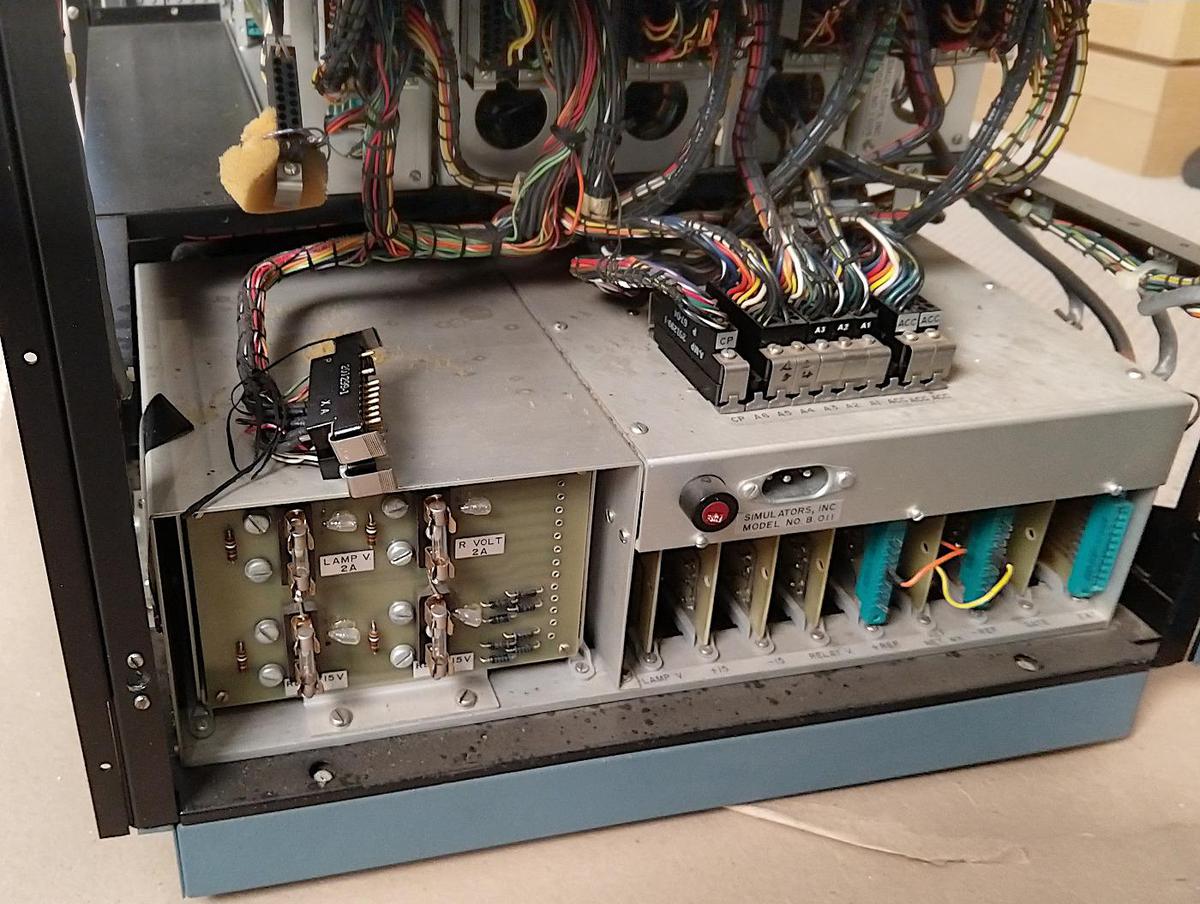

The photo above shows the power supply in the lower back section of the analog computer. The power supply is more complex than I expected. The section on the left converts line-voltage AC into low-voltage AC and DC. These outputs go to the card cage on the right, which has 8 circuit boards that regulate the voltages. The complex wiring harnesses on top of the power supply provide power to the five analog computation modules above the power supply as well as the rest of the computer.

With a vintage computer, it's important to make sure the power supply is working properly, since if it is generating the wrong voltages, the results could be catastrophic. So we proceed methodically, first checking the components in the power supply, then testing the power supply outputs while disconnected from the rest of the computer, and finally powering up the whole computer.

The transformer / rectifier section

We started by removing the power supply from the computer, and disconnecting the two halves. The left half of the power supply (below) produces four unregulated DC outputs and a low-voltage AC output. In contains two large power transformers, four large filter capacitors, stud rectifiers (upper back), smaller diodes (front right), and fuses. This is a large and very heavy module because of the transformers.2 The smaller transformer powers the lamps and relays, while the larger transformer powers the +15 and -15 volt supplies as well as the oscillator. Presumably, using separate transformers prevents noise and fluctuations from the lamps and relays from affecting the precision reference supplies.

One concern with old power supplies is that the electrolytic capacitors can dry out and fail over time. (These capacitors are the large cylinders above.) We measured the capacitance and resistance of the large capacitors (using Marc's vintage HP LCR meter) and they tested okay. We also checked the input resistance of the power supply to make sure there weren't any obvious shorts; everything seemed fine.

We removed all the cards from the card cage, cautiously plugged in the power supply, and... nothing at all happened. For some reason, no AC voltage was getting to the power supply. The fuse was an obvious suspect, but it was fine. Carl asked about the power switch on the control panel, and we figured out that the switch was connected to the power supply via the socket labeled "CP" (below). We added a jumper, powered up the supply, and this time found the expected DC voltages from the module.

The regulator cards

Next, we tested the power supply's various cards individually. The power supply has four regulator cards generating "lamp voltage", "+15", "-15", and "relay voltage". The purpose of a regulator card is to take an unregulated DC voltage from the transformer module and reduce it to the desired output voltage.

We hooked up the regulator cards using a bench power supply as input to make sure they were working properly. We tweaked the potentiometer on the +15 V regulator to get exactly 15 V output. The -15 V regulator seemed temperamental and the voltage jumped around when we adjusted it. I suspected a dirty potentiometer, but it settled down to a stable output (narrator: this is foreshadowing). We don't know what the lamp and relay voltages are supposed to be, and they're not critical, so we left those boards unadjusted.

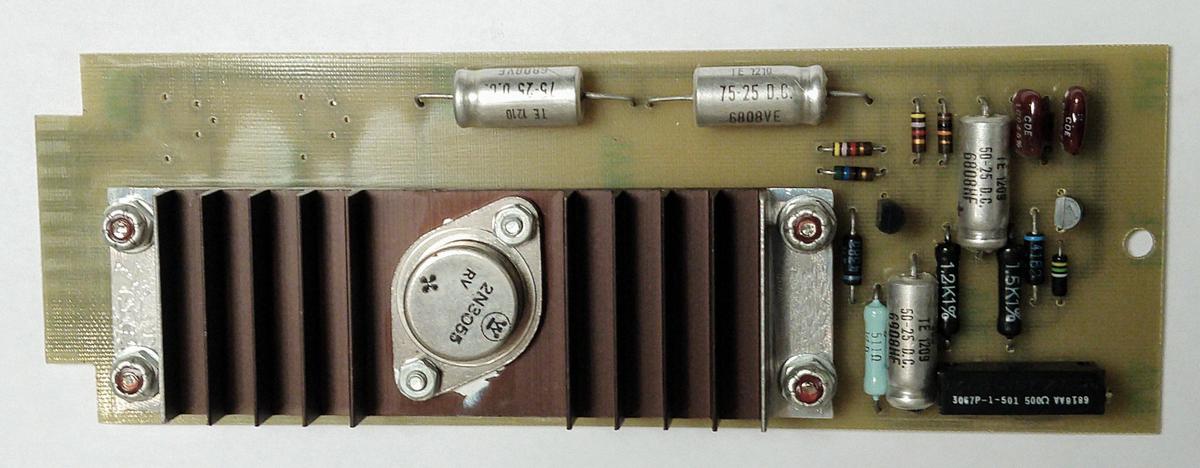

The photo above shows one of the regulator cards; you might think it has a lot of components just to regulate a voltage. The first voltage regulator chip was created in 1966, so this computer uses a linear regulator built from individual components instead. The large metal transistor on the heat sink is the heart of the voltage regulator; it acts kind of like a variable resistor to control the output. The rest of the components provide the control signal to this transistor to produce the desired output. A Zener diode (yellow and green stripes on the right) acts as the voltage reference, and the output is compared to this reference. A smaller transistor generates the control signal for the power transistors. In the lower right, a multi-turn potentiometer is used to adjust the voltage output. The larger capacitors (metal cylinders) filter the voltage, while the smaller capacitors ensure stability. Most power supply of just a few years later would replace all of these components (except the filter capacitors) with a voltage regulator IC.

The chopper oscillator

The precision op amps in the analog computer use a chopper circuit for better DC performance, and the chopper requires 400 Hertz pulses. These pulses are generated by the oscillator board in the power supply (called the gate for some reason). We powered up the board separately to test it, and found it produced 370 Hz, which seemed close enough.

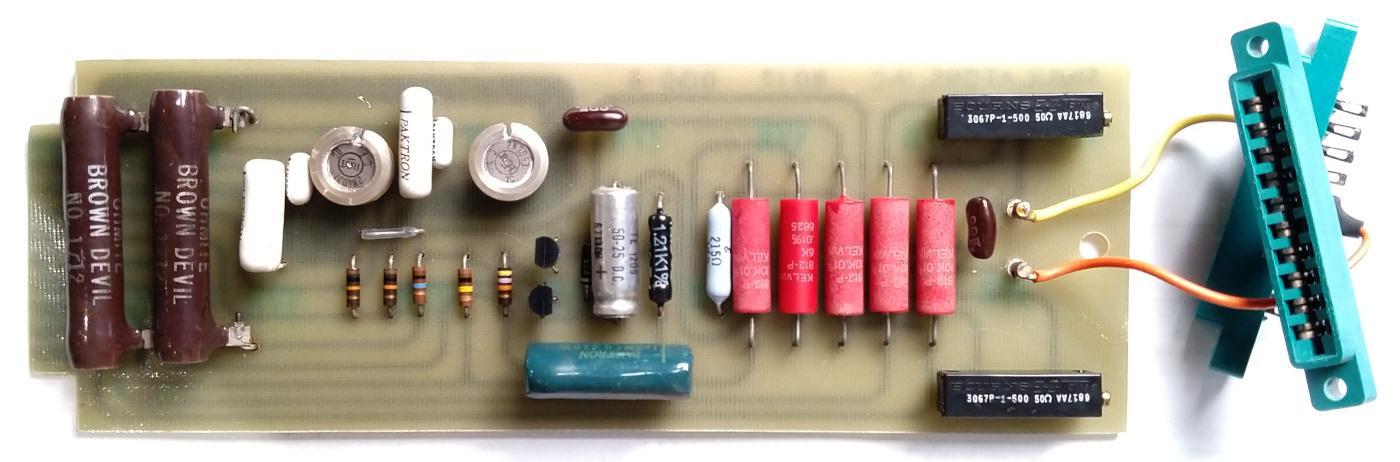

The circuitry of this card is somewhat bizarre, and not what I was expecting on an oscillator card. The left side has three large capacitors and three diodes, powered by low-voltage AC from the transformer. After puzzling over this for a bit, I determined it was a full-wave voltage doubler, producing DC at twice the voltage of the AC input. I assume that the chopper pulses needed to be higher voltage than the computer's +15 volt supply, so they used this voltage doubler to get enough voltage swing.

The oscillator itself (right side of the card), uses one NPN transistor as an oscillator, and another NPN transistor as a buffer. It took me a while to figure out how a single-transistor oscillator works. It turns out to be a phase-shift oscillator; the three white capacitors in the middle of the board shift the signal 180°; inverting it causes oscillation.

The op amps

Calculations in the analog computer are referenced to +10 volt and -10 volt reference voltages, so these voltages need to be very accurate. The regulator cards produce fairly stable voltages, but not good enough. (While testing the regulator cards, I noticed that the output voltage shifted noticeably as I changed the input voltage.) To achieve this accuracy, the reference voltages are generated by op amp circuits, built from two op amp boards and a feedback network card.

Somewhat surprisingly, the op amp cards used in the power supply are exactly the same as the precision op amps used in the analog computer itself. Back in 1969, op amp integrated circuits weren't accurate enough for the analog computer, so the designers of this analog computer combined an op amp chip with a chopper circuit and many other parts to create a high-performance op ap card. I described the op amp cards in detail in the first post, so I won't go into more detail here.

The network card

The network card has two jobs. First, it has precision resistors to create the feedback networks for the power supply op amps. Second, it has two power transistors (circular metal components below) that buffer the reference voltages from the op amp for use by the rest of the computer.

One of the problems with an analog computer is that the results are only as accurate as the components. In other words, if the 10 volt reference is off by 1%, your answers will be off by 1%. The result is that analog computers need expensive, high-precision resistors. (In contrast, the voltages in a digital computer can drift a lot, as long as a 0 and a 1 can be distinguished. This is one reason why digital computers replaced analog computers.) Typical resistors have a tolerance of 20%, which means the resistance can be up to 20% different from the indicated value. More expensive resistors have tolerance of 10%, 5%, or even 1%. But the resistors on this board have tolerance of 0.01%! (These resistors are the pink cylinders.) The two large resistors on the left are 15Ω "Brown Devil" power resistors. They protect the voltage outputs in case someone plugs the wrong wire into the patch panel and shorts an output, which would be easy to do.

The network card receives an adjustment voltage from the control panel, and also has multi-turn potentiometers on the right for adjustment (like the regulator cards). The green connectors are used to connect the network card to the op amp cards. (The op amps have a separate connector for the input, to reduce electrical noise.)

Powering it up and fixing a problem

Finally, we put all the power supply boards back in the cabinet, put the power supply back in the computer, and powered up the chassis (but not the analog computer modules). Some of the indicator lights on the control panel lit up and the +15 V supply showed up on the meter. However, the -15 V supply wasn't giving any voltage, and the op amp overload lights were illuminated on the front panel, and the reference voltages from the op amps weren't there. The bad -15 V supply looked like the first thing to investigate, since without it, the op amp boards wouldn't work.

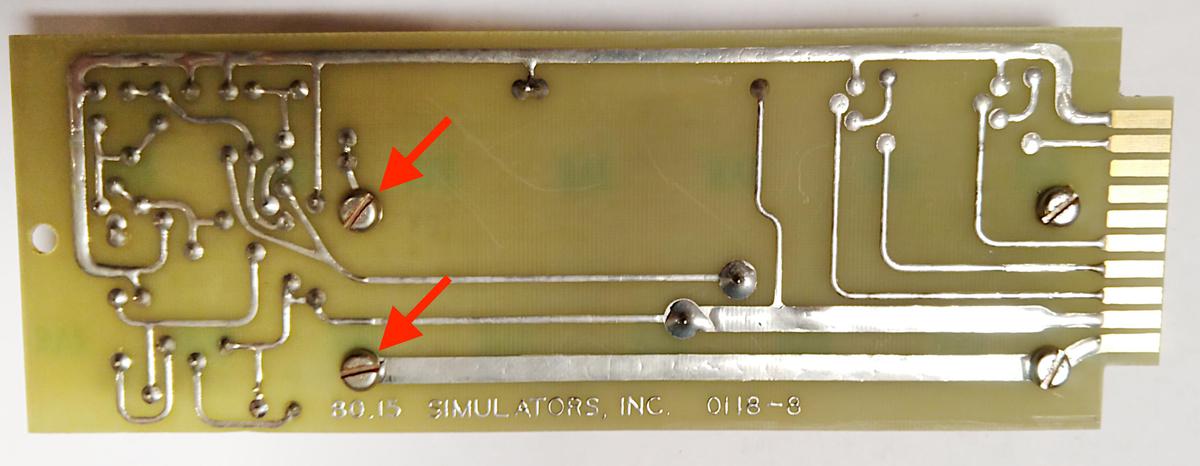

I removed the working +15 regulator and failing -15 regulator from the card cage and tested them on the bench. Conveniently, both boards are identical, so I could easily compare signals on the two boards. (Modern circuits typically use special regulators for negative voltage outputs, but this power supply used the same regulator for both.) The output transistor on the bad board wasn't getting any control signal on its base, so it wasn't producing any output. Tracing the signals back, I found the transistor generating this signal wasn't getting any voltage. This transistor was powered directly from the connector, so why wasn't any voltage getting to the transistor?

I studied the printed circuit board and noticed that there wasn't a PCB trace between the transistor and the connector! Instead, part of the current path was through the heat sink. The heat sink was screwed down to the PCB, making a connection between the two red arrows above. After I tightened all the screws, the board worked fine.

We put the boards back in, powered up the chassis, and this time the voltages all seemed to be correct. The op amp overload warning lights remained off; the warning light went on before because the op amps couldn't operate with one voltage missing. The next step is to power up the analog circuitry modules and test them. We also need to repair the separate 5-volt power supply used by the digital logic since we found some bad capacitors that will need to be replaced. So those are tasks for the next sessions.

Follow me on Twitter @kenshirriff to stay informed of future articles. I also have an RSS feed.

Notes and references

-

The computer's integrated circuits have 1968 and 1969 date codes on them, so I think the computer was manufactured in 1969. ↩

-

Most modern power supplies are switching power supplies, so they are much smaller and lighter than linear power supplies like the one in the analog computer. (Your laptop charger, for instance, is a switching power supply.) Back in this era, switching power supplies were fairly exotic. However, linear power supplies are still sometimes used since they have less noise than switching power supplies. ↩

Perhaps the oscillator was called a "gate" because of how it operates. The nickname "chopper" supports this theory: In music synthesis jargon, a gated signal is one that is attenuated or interrupted by another signal.

ReplyDeleteChopper amplifiers were frequently used as laboratory equipment, and optical choppers were common until high performance solid-state amplifiers became available. As it was explained to me, a lamp behind a slotted rotating disc (think: optical encoder disk) "gated" the light to photoresistors in an alternating sequence, to apply the input to, and null across, the amplifier repeatedly.

ReplyDelete