Half a century ago, the puzzling phrase "special register groups" started showing up in definitions of "CPU", and it is still there. In this blog post, I uncover how special register groups went from an obscure feature in the Honeywell 800 mainframe to appearing in the Washington Post.

While researching old computers, I found a strange definition of "Central Processing Unit" that keeps appearing in different sources. From a book reprinted in 2017:1

At first glance, this definition seems okay, but a few moments thought reveals some problems. Storage is not part of the CPU. But more puzzling, what are special register groups? A CPU has registers, but "special register groups" is not a normal phrase.

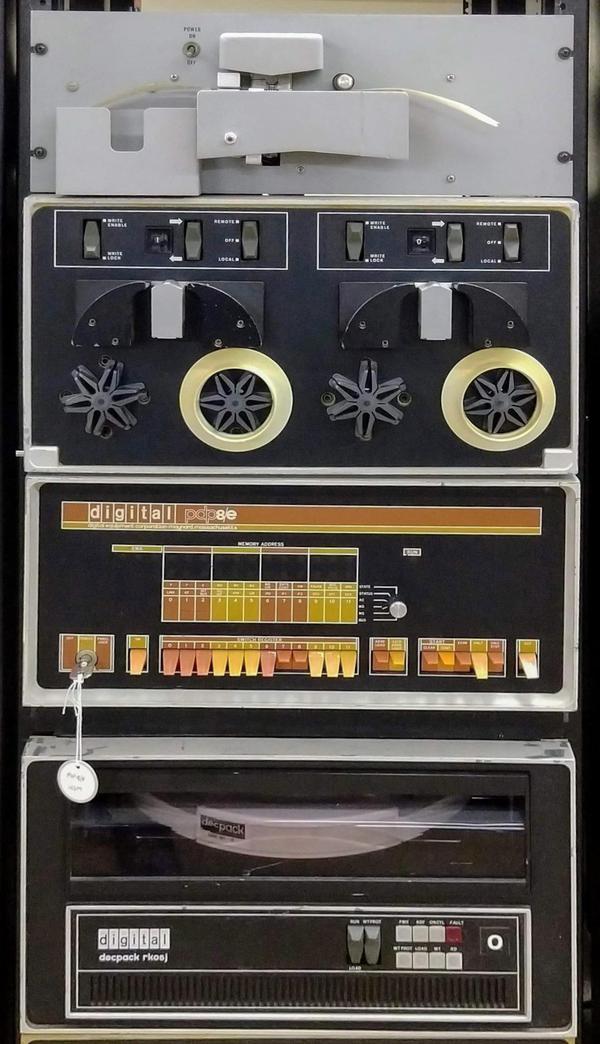

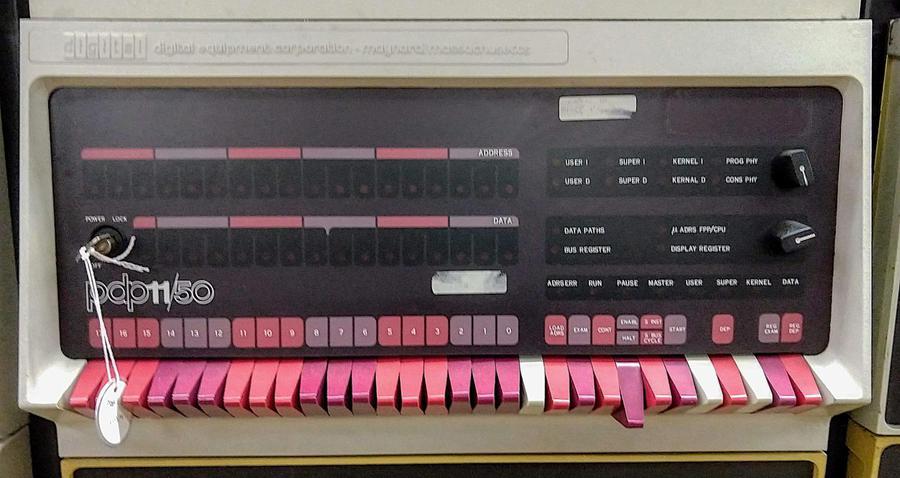

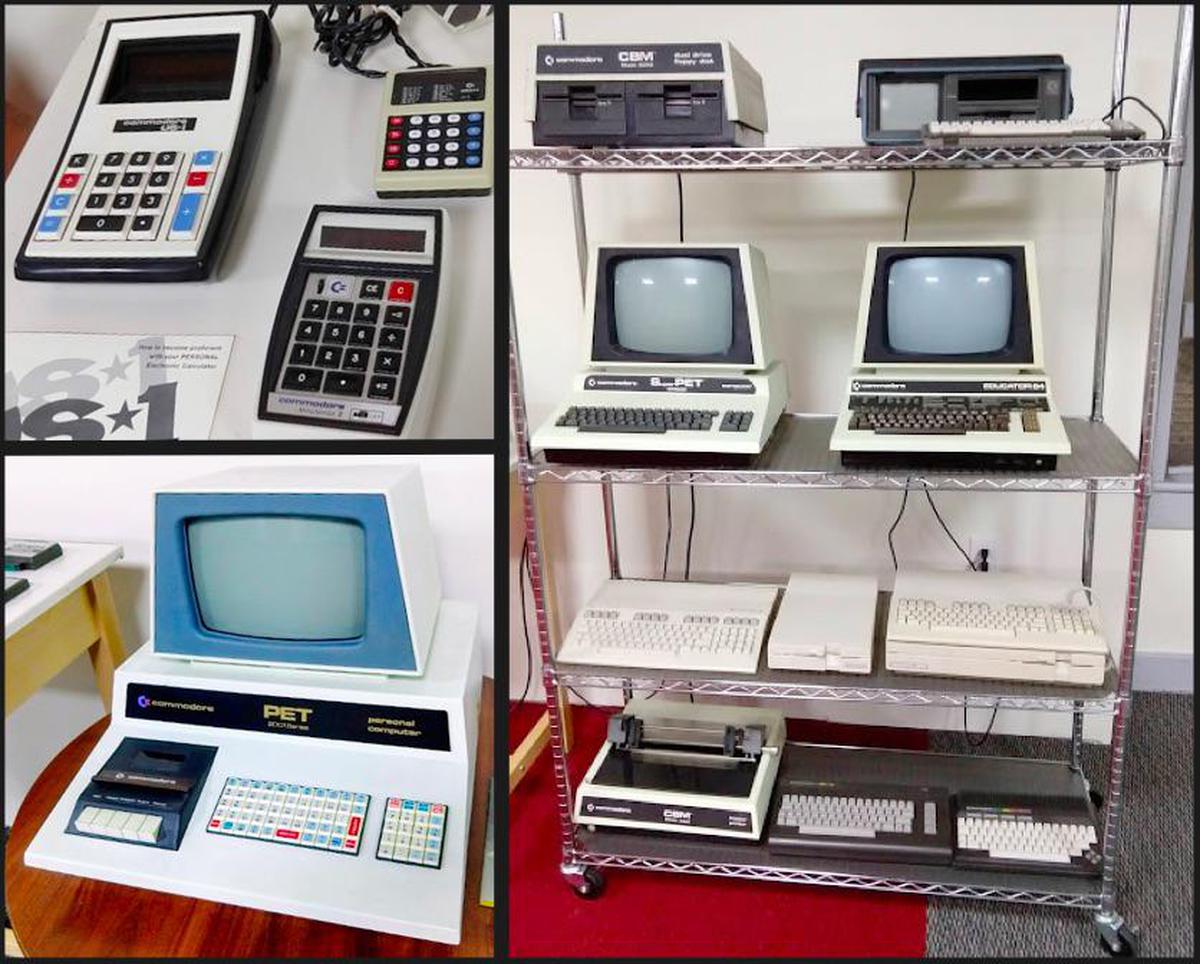

It turns out that this definition has been used extensively for over half a century, even though it doesn't make sense, copied and modified from one source to another. Special register groups were a feature in the Honeywell 800 mainframe computer, introduced in 1959. Although this computer is long-forgotten2, its impact inexplicably remains in many glossaries. The Honeywell 800 allowed eight programs to run on a single processor, switching between programs after every instruction.3 To support this, each program had a "special register group" in hardware, its own separate group of 32 registers (program counter, general-purpose registers, index registers, etc.).

Another important thing to note about that era is the central processing unit was a large physical box, also known as the "main frame". (A mainframe was not a type of computer yet.) Thus, given the characteristics of the Honeywell 800, the definition of CPU in Honeywell's glossary4 made total sense.5 Unfortunately, this definition doesn't make sense when used for computers in general, since they lack special register groups.

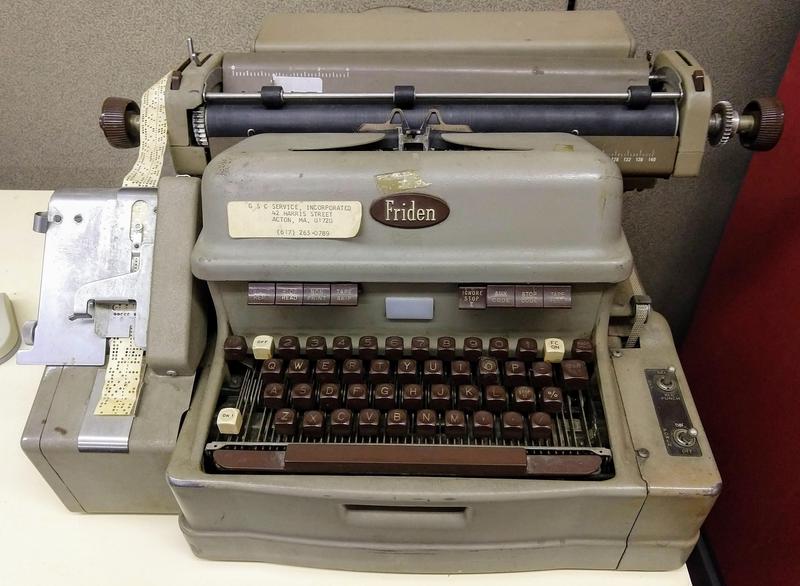

This definition apparently started with the US Department of Agriculture's Glossary of ADP Terminology (1960): "MAIN FRAME - The central processor of the computer system. It contains the main memory, arithmetic unit and special register groups". The definition then spread through the government. The Bureau of the Budget published the Automatic Data Processing Glossary in 1962 "for use as an authoritative reference by all officials and employees of the executive branch of the Government" with the definition below. The Air Force's 1966 Guide for Auditing Automatic Data Processing Systems used a similar definition as did the 1966 Navy Training Course for Machine Accountant and 1968 Air Force manual Communications-Electronics Terminology.

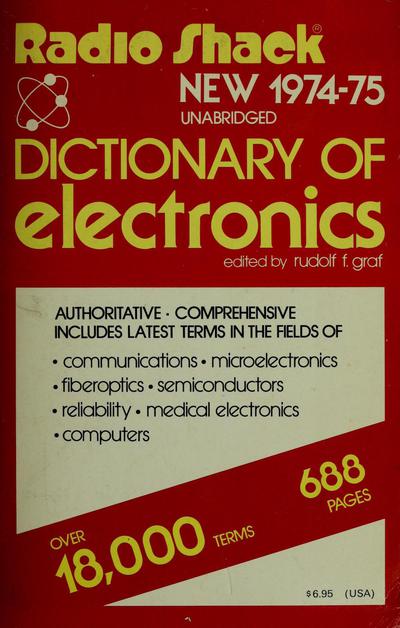

From there, the definition spread to dozens of books and dictionaries. The "special register groups" appeared in numerous computer glossaries such as the Glossary of Computing Terminology (1972), Computer Glossary for Medical and Health Sciences (1973) Computer Glossary for Engineers and Scientists (1973), Radio Shack's Dictionary of Electronics (1968, 1974-1975), and Computer Graphics Glossary (1983)

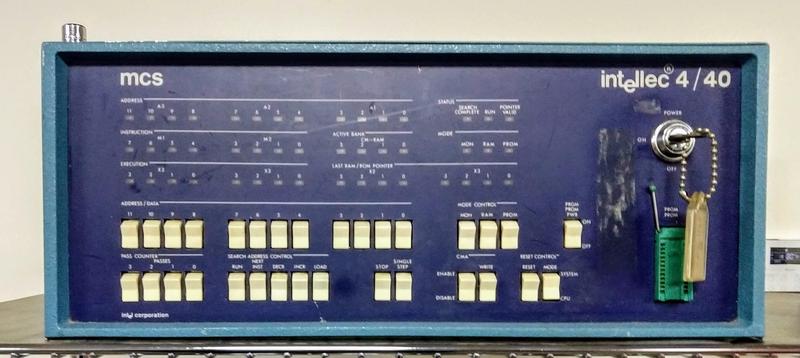

Computer manufacturers should know their systems don't have special register groups, but they still used the definition. For example, Sphere microcomputer (1976), Texas Instruments (1978), Cray (1984), Convergent Technologies (1987), and Tektronix (1989).

This definition persisted into the microcomputer age, even though storage was now clearly not part of the CPU and "special register groups" were decades in the past. A 1983 Beginner's Computer Glossary in MICRO magazine defined "CPU — Central Processing Unit. The central processor of the computer system, which contains the main storage, arithmetic unit, and special register groups." "Special register groups" also showed up in Microcomputer Dictionary (1981), and Understanding Microprocessors (1984),

Definitions with "special register groups" appeared in a dizzying array of books, such as Computer Technology in the Health Sciences (1974), College Typewriting (1975), Research Methods for Recreation and Leisure (1979), EPA's Design Automation Handbook for Automation of Activated Sludge Treatment Plants (1980), Patrick-Turner's Industrial Automation Dictionary (1996), Video Scrambling & Descrambling (1998), US Department of Transportation's Computerized Signal Systems (1979). and Traffic Control System Operations (2000).

In 1981, special register groups reached national newspapers in a Washington Post glossary: "Main-frame—central processor of computer system, containing main storage, arithmetic unit and special register groups." By 2006, even the National Fire Code6 included special register groups: "Computer. A programmable electronic device that contains a central processing unit(s), main storage, an arithmetic unit, and special register groups."

Special register groups are still being taught to the next generation of students. The following quiz question is from a 2017 book that teaches computer organization and programming:7

CPU of a computer system does not contain: (a) Main storage (b) Arithmetic unit (c) Special register group (d) None of the above

Conclusion

For some reason, a 1960 definition of "central processing unit" included "special register groups", an obscure feature from the Honeywell 800 mainframe. This definition was copied and changed for decades, even though it doesn't make sense. It appears that once something appears in an authoritative glossary, people will reuse it for decades, and obsolete terms may never die out.

Researching this phrase also shows how the meanings of computer terms shift greatly over time. In 1960, "main frame" and "CPU" were synonyms, but since then they have moved in opposite directions: "mainframe" is now a large computer system, while the "CPU" is usually a processor chip. (I plan to write much more about this.)

I announce my latest blog posts on Twitter, so follow me @kenshirriff for future articles. I also have an RSS feed.

Notes and References

-

Reference: Reliability Engineering for Nuclear and Other High Technology Systems, CRC Press, 2017, reprint of a book originally published in 1985. ↩

-

I happen to be familiar with the Honeywell 800 and 1800 computers because I've been studying the Apollo Guidance Computer extensively. (The Honeywell 1800 was an improved version of the Honeywell 800.) The Honeywell 1800 was used to assemble programs for the Apollo Guidance Computer using an assembler called YUL. ↩

-

The Honeywell 800's technique of switching programs on every instruction is rather unusual. Typical multi-tasking systems let a program run for several milliseconds before switching to another program to reduce the overhead of switching between programs. The Honeywell 800 Programmers Reference Manual explains the use of special register groups for multiprogramming. ↩

-

Honeywell's Glossary of Data Processing and Communications Terms was published 1964-1966. Definitions in that book are largely based on the Bureau of the Budget's Automatic Data Processing Glossary. ↩

-

The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) quoted the 1964 Honeywell definition. ↩

-

Reference: NFPA's Illustrated Dictionary of Fire Service Terms, published by the National Fire Protection Association in 2006. The National Fire Codes (1995) had a somewhat similar definition, but for the CPU instead of computer: "CPU. Central processing unit of the computer system. The CPU contains the main storage, arithmetic unit, and special register groups." ↩

-

Reference: Computer Architecture, 2011, published by Biyani. Page 58 contains the quiz with the CPU question. The question also appears in MCS-012: Computer Organisation and Assembly Language Programming, 2017. ↩