Switching power supplies are now very cheap, but this wasn't always the case. In the 1950s, switching power supplies were complex and expensive, used in aerospace and satellite applications that needed small, lightweight power supplies. By the early 1970s, new high-voltage transistors and other technology improvements made switching power supplies much cheaper and they became widely used in computers.[2] The introduction of a single-chip power supply controller in 1976 made switching power supplies simpler, smaller, and cheaper.

Apple's involvement with switching power supplies goes back to 1977 when Apple's chief engineer Rod Holt designed a switching power supply for the Apple II. According to Steve Jobs:[3]

"That switching power supply was as revolutionary as the Apple II logic board was. Rod doesn't get a lot of credit for this in the history books but he should. Every computer now uses switching power supplies, and they all rip off Rod Holt's design."

This is a fantastic quote, but unfortunately it is entirely false. The switching power supply revolution happened before Apple came along, Apple's design was similar to earlier power supplies[4] and other computers don't use Rod Holt's design. Nevertheless, Apple has extensively used switching power supplies and pushes the limits of charger design with their compact, stylish and advanced chargers.

Inside the charger

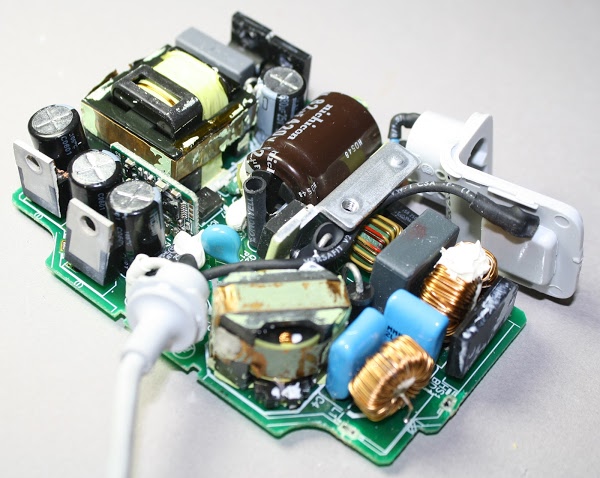

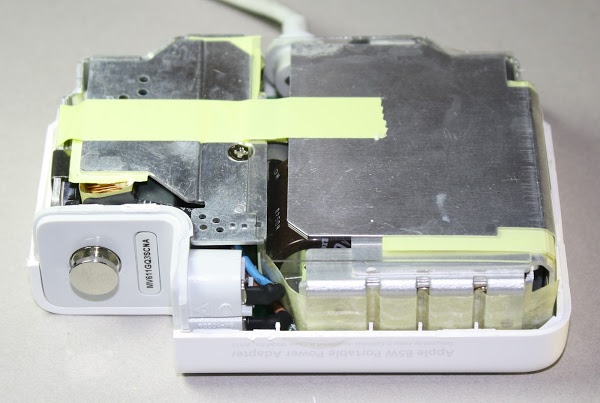

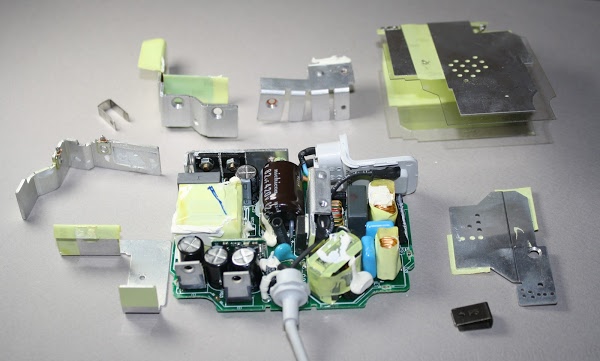

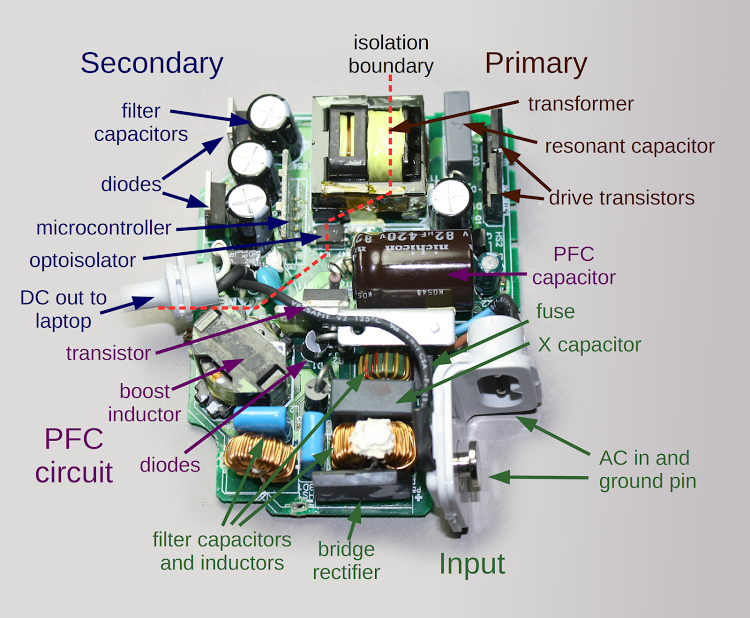

For the teardown I started with a Macbook 85W power supply, model A1172, which is small enough to hold in your palm. The picture below shows several features that can help distinguish the charger from counterfeits: the Apple logo in the case, the metal (not plastic) ground pin on the right, and the serial number next to the ground pin.

AC enters the charger

AC power enters the charger through a removable AC plug. A big advantage of switching power supplies is they can be designed to run on a wide range of input voltages. By simply swapping the plug, the charger can be used in any region of the world, from European 240 volts at 50 Hertz to North American 120 volts at 60 Hz. The filter capacitors and inductors in the input stage prevent interference from exiting the charger through the power lines. The bridge rectifier contains four diodes, which convert the AC power into DC. (See this video for a great demonstration of how a full bridge rectifier works.)

PFC: smoothing the power usage

The next step in the charger's operation is the Power Factor Correction circuit (PFC), labeled in purple. One problem with simple chargers is they only draw power during a small part of the AC cycle.[5] If too many devices do this, it causes problems for the power company. Regulations require larger chargers to use a technique called power factor correction so they use power more evenly.

The PFC circuit uses a power transistor to precisely chop up the input AC tens of thousands of times a second; contrary to what you might expect, this makes the load on the AC line smoother. Two of the largest components in the charger are the inductor and PFC capacitor that help boost the voltage to about 380 volts DC.[6]

The primary: chopping up the power

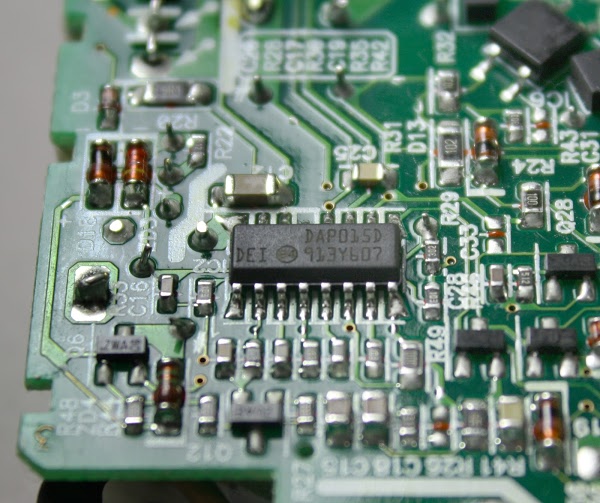

The primary circuit is the heart of the charger. It takes the high voltage DC from the PFC circuit, chops it up and feeds it into the transformer to generate the charger's low-voltage output (16.5-18.5 volts). The charger uses an advanced design called a resonant controller, which lets the system operate at a very high frequency, up to 500 kilohertz. The higher frequency permits smaller components to be used for a more compact charger. The chip below controls the switching power supply.[7]

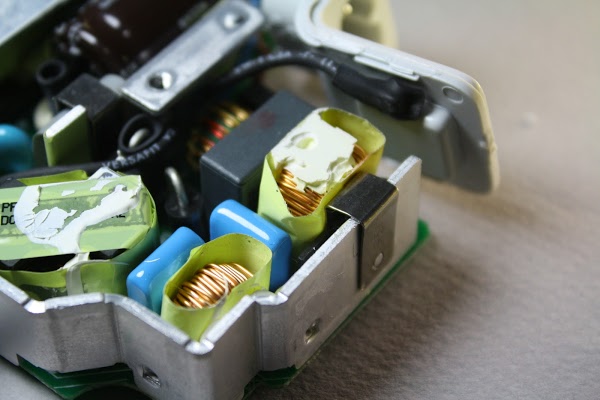

The two drive transistors (in the overview diagram) alternately switch on and off to chop up the input voltage. The transformer and capacitor resonate at this frequency, smoothing the chopped-up input into a sine wave.

The secondary: smooth, clean power output

The secondary side of the circuit generates the output of the charger. The secondary receives power from the transformer and converts it DC with diodes. The filter capacitors smooth out the power, which leaves the charger through the output cable.

The most important role of the secondary is to keep the dangerous high voltages in the rest of the charger away from the output, to avoid potentially fatal shocks. The isolation boundary marked in red on the earlier diagram indicates the separation between the high-voltage primary and the low-voltage secondary. The two sides are separated by a distance of about 6 mm, and only special components can cross this boundary.

The transformer safely transmits power between the primary and the secondary by using magnetic fields instead of a direct electrical connection. The coils of wire inside the transformer are triple-insulated for safety. Cheap counterfeit chargers usually skimp on the insulation, posing a safety hazard. The optoisolator uses an internal beam of light to transmit a feedback signal between the secondary and primary. The control chip on the primary side uses this feedback signal to adjust the switching frequency to keep the output voltage stable.

A powerful microprocessor in your charger?

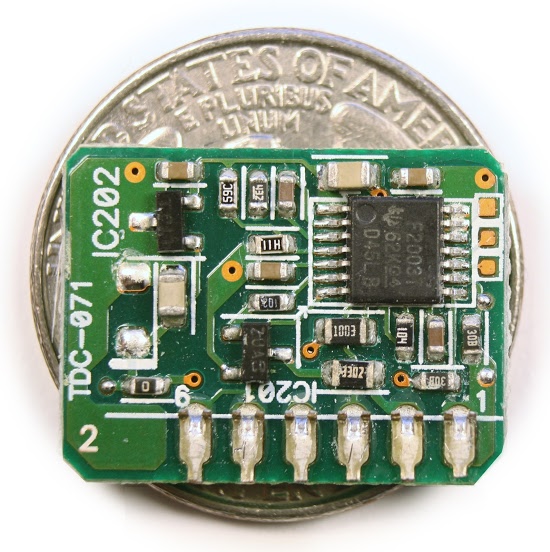

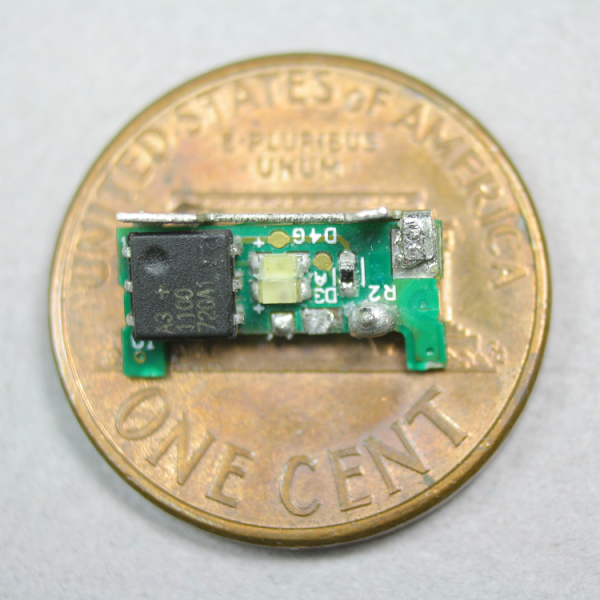

One unexpected component is a tiny circuit board with a microcontroller, which can be seen above. This 16-bit processor constantly monitors the charger's voltage and current. It enables the output when the charger is connected to a Macbook, disables the output when the charger is disconnected, and shuts the charger off if there is a problem. This processor is a Texas Instruments MSP430 microcontroller, roughly as powerful as the processor inside the original Macintosh.[8]

The square orange pads on the right are used to program software into the chip's flash memory during manufacturing.[9] The three-pin chip on the left (IC202) reduces the charger's 16.5 volts to the 3.3 volts required by the processor.[10]

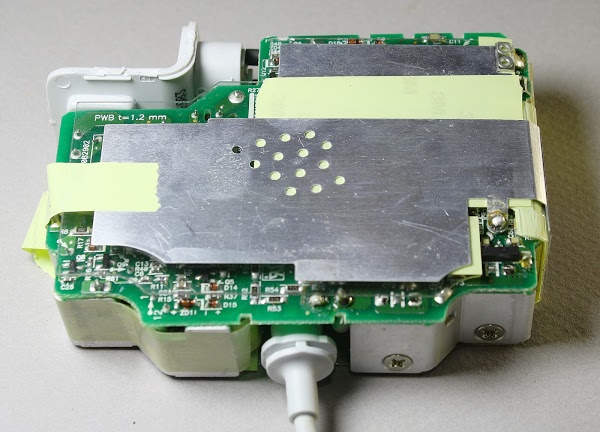

The charger's underside: many tiny components

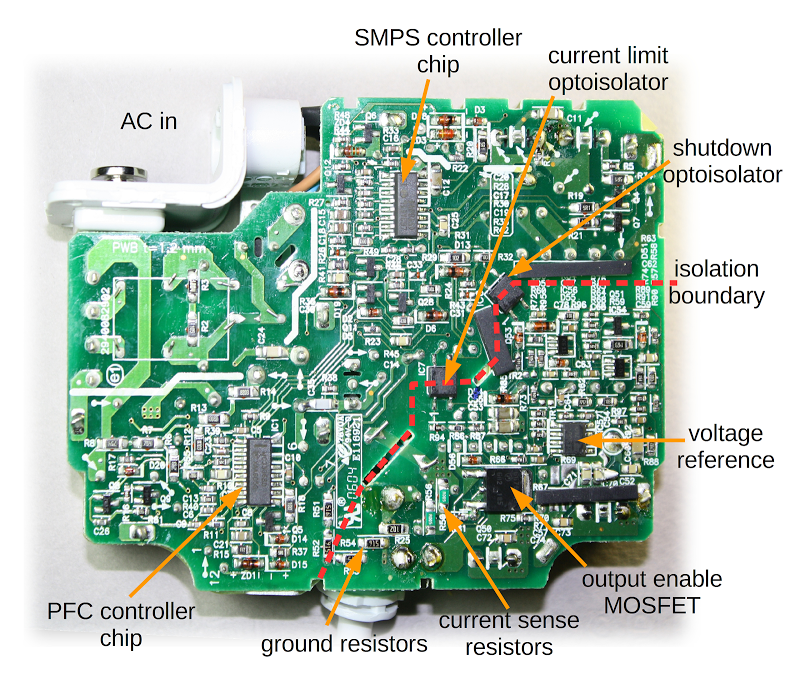

Turning the charger over reveals dozens of tiny components on the circuit board. The PFC controller chip and the power supply (SMPS) controller chip are the main integrated circuits controlling the charger. The voltage reference chip is responsible for keeping the voltage stable even as the temperature changes.[11] These chips are surrounded by tiny resistors, capacitors, diodes and other components. The output MOSFET transistor switches the power to the output on and off, as directed by the microcontroller. To the left of it, the current sense resistors measure the current flowing to the laptop.

One reason the charger has more control components than a typical charger is its variable output voltage. To produce 60 watts, the charger provides 16.5 volts at 3.6 amps. For 85 watts, the voltage increases to 18.5 volts at 4.6 amps. This allows the charger to be compatible with lower-voltage 60 watt chargers, while still providing 85 watts for laptops that can use it.[13] As the current increases above 3.6 amps, the circuit gradually increases the output voltage. If the current increases too much, the charger abruptly shuts down around 90 watts.[14]

Inside the Magsafe connector

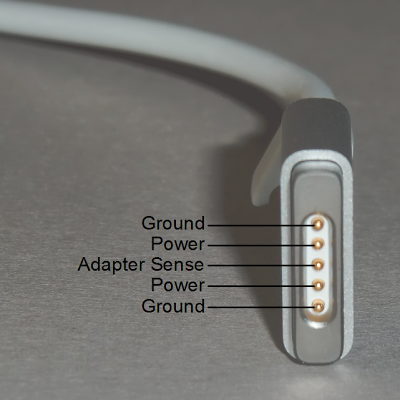

The magnetic Magsafe connector that plugs into the Macbook is more complex than you would expect. It has five spring-loaded pins (known as Pogo pins) to connect to the laptop. Two pins are power, two pins are ground, and the middle pin is a data connection to the laptop.

Operation of the charger

You may have noticed that when you plug the connector into a Macbook, it takes a second or two for the LED to light up. During this time, there are complex interactions between the Macbook, the charger, and the Magsafe connector.When the charger is disconnected from the laptop, the output transistor discussed earlier blocks the output power.[15] When the Magsafe connector is plugged into a Macbook, the laptop pulls the power line low.[16] The microcontroller in the charger detects this and after exactly one second enables the power output. The laptop then loads the charger information from the Magsafe connector chip. If all is well, the laptop starts pulling power from the charger and sends a command through the data pin to light the appropriate connector LED. When the Magsafe connector is unplugged from the laptop, the microcontroller detects the loss of current flow and shuts off the power, which also extinguishes the LEDs.

You might wonder why the Apple charger has all this complexity. Other laptop chargers simply provide 16 volts and when you plug it in, the computer uses the power. The main reason is for safety, to ensure that power isn't flowing until the connector is firmly attached to the laptop. This minimizes the risk of sparks or arcing while the Magsafe connector is being put into position.

Why you shouldn't get a cheap charger

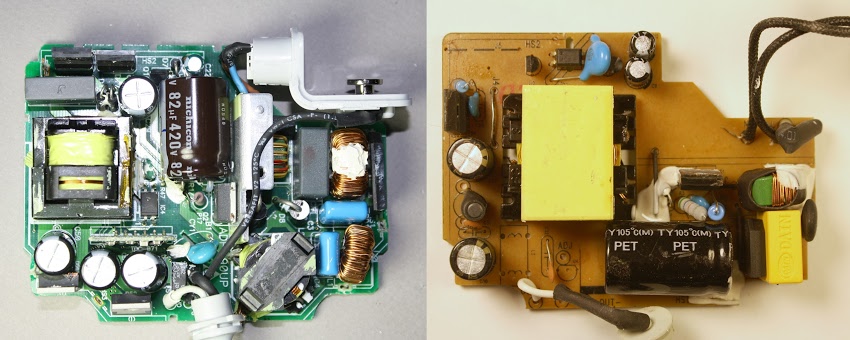

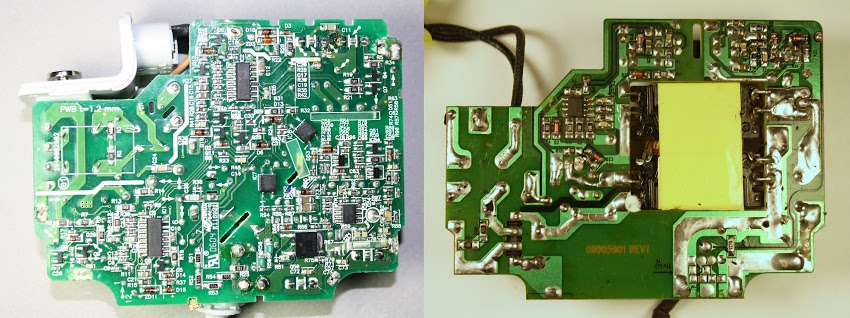

The Macbook 85W charger costs $79 from Apple, but for $14 you can get a charger on eBay that looks identical. Do you get anything for the extra $65? I opened up an imitation Macbook charger to see how it compares with the genuine charger. From the outside, the charger looks just like an 85W Apple charger except it lacks the Apple name and logo. But looking inside reveals big differences. The photos below show the genuine Apple charger on the left and the imitation on the right.

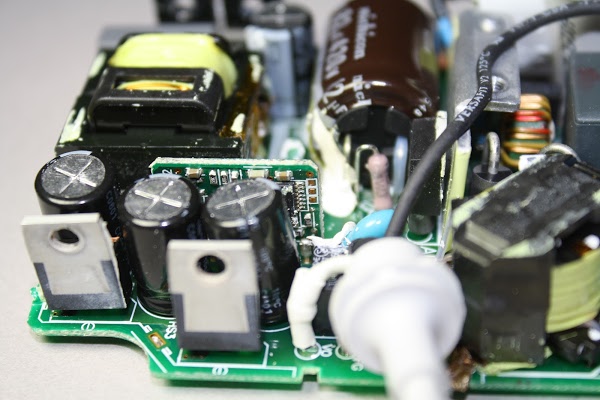

The imitation charger has about half the components of the genuine charger and a lot of blank space on the circuit board. While the genuine Apple charger is crammed full of components, the imitation leaves out a lot of filtering and regulation as well as the entire PFC circuit. The transformer in the imitation charger (big yellow rectangle) is much bulkier than in Apple's charger; the higher frequency of Apple's more advanced resonant converter allows a smaller transformer to be used.

Flipping the chargers over and looking at the circuit boards shows the much more complex circuitry of the Apple charger. The imitation charger has just one control IC (in the upper left).[17] since the PFC circuit is omitted entirely. In addition, the control circuits are much less complex and the imitation leaves out the ground connection.

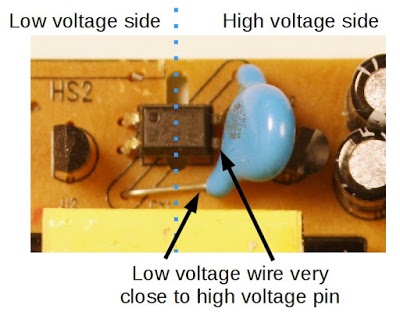

The imitation charger is actually better quality than I expected, compared to the awful counterfeit iPad charger and iPhone charger that I examined. The imitation Macbook charger didn't cut every corner possible and uses a moderately complex circuit. The imitation charger pays attention to safety, using insulating tape and keeping low and high voltages widely separated, except for one dangerous assembly error that can be seen below. The Y capacitor (blue) was installed crooked, so its connection lead from the low-voltage side ended up dangerously close to a pin on the high-voltage side of the optoisolator (black), creating a risk of shock.

Problems with Apple's chargers

The ironic thing about the Apple Macbook charger is that despite its complexity and attention to detail, it's not a reliable charger. When I told people I was doing a charger teardown, I rapidly collected a pile of broken chargers from people who had failed chargers. The charger cable is rather flimsy, leading to a class action lawsuit stating that the power adapter dangerously frays, sparks and prematurely fails to work. Apple provides detailed instructions on how to avoid damaging the wire, but a stronger cable would be a better solution. The result is reviews on the Apple website give the charger a dismal 1.5 out of 5 stars.

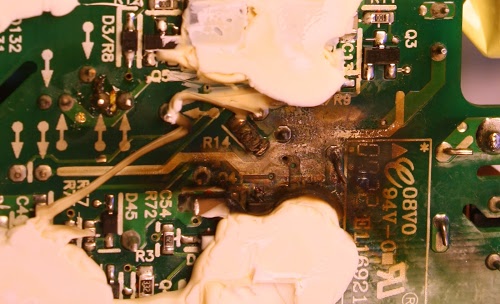

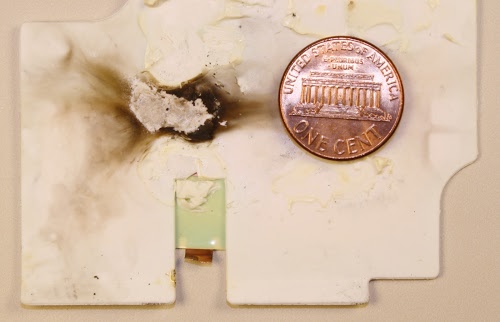

Macbook chargers also fail due to internal problems. The photos above and below show burn marks inside a failed Apple charger from my collection.[18] I can't tell exactly what went wrong, but something caused a short circuit that burnt up a few components. (The white gunk in the photo is insulating silicone used to mount the board.)

Why Apple's chargers are so expensive

As you can see, the genuine Apple charger has a much more advanced design than the imitation charger and includes more safety features. However, the genuine charger costs $65 more and I doubt the additional components cost more than $10 to $15[19]. Most of the cost of the charger goes into the healthy profit margin that Apple has on their products. Apple has an estimated 45% profit margin on iPhones[20] and chargers are probably even more profitable. Despite this, I don't recommend saving money with a cheap eBay charger due to the safety risk.

Conclusion

People don't give much thought to what's inside a charger, but a lot of interesting circuitry is crammed inside. The charger uses advanced techniques such as power factor correction and a resonant switching power supply to produce 85 watts of power in a compact, efficient unit. The Macbook charger is an impressive piece of engineering, even if it's not as reliable as you'd hope. On the other hand, cheap no-name chargers cut corners and often have safety issues, making them risky, both to you and your computer.Notes and references

[1] The main alternative to a switching power supply is a linear power supply, which is much simpler and converts excess voltage to heat. Because of this wasted energy, linear power supplies are only about 60% efficient, compared to about 85% for a switching power supply. Linear power supplies also use a bulky transformer that may weigh multiple pounds, while switching power supplies can use a tiny high-frequency transformer.[2] Switching power supplies were taking over the computer industry as early as 1971. Electronics World said that companies using switching regulators "read like a 'Who's Who' of the computer industry: IBM, Honeywell, Univac, DEC, Burroughs, and RCA, to name a few". See "The Switching Regulator Power Supply", Electronics World v86 October 1971, p43-47. In 1976, Silicon General introduced SG1524 PWM integrated circuit, which put the control circuitry for a switching power supply on a single chip.

[3] The quote about the Apple II power supply is from page 74 of the 2011 book Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson. It inspired me to write a detailed history of switching power supplies: Apple didn't revolutionize power supplies; new transistors did. Steve Job's quote sounds convincing, but I consider it the reality distortion field in effect.

[4] If anyone can take the credit for making switching power supplies an inexpensive everyday product, it is Robert Boschert. He started selling switching power supplies in 1974 for everything from printers and computers to the F-14 fighter plane. See Robert Boschert: A Man Of Many Hats Changes The World Of Power Supplies in Electronic Design. The Apple II's power supply is very similar to the Boschert OL25 flyback power supply but with a patented variation.

[5] You might expect the bad power factor is because switching power supplies rapidly turn on and off, but that's not the problem. The difficulty comes from the nonlinear diode bridge, which charges the input capacitor only at peaks of the AC signal. (If you're familiar with power factors due to phase shift, this is totally different. The problem is the non-sinusoidal current, not a phase shift.)

The idea behind PFC is to use a DC-DC boost converter before the switching power supply itself. The boost converter is carefully controlled so its input current is a sinusoid proportional to the AC waveform. The result is the boost converter looks like a nice resistive load to the power line, and the boost converter supplies steady voltage to the switching power supply components.

[6] The charger uses a MC33368 "High Voltage GreenLine Power Factor Controller" chip to run the PFC. The chip is designed for low power, high-density applications so it's a good match for the charger.

[7] The SMPS controller chip is a L6599 high-voltage resonant controller; for some reason it is labeled DAP015D. It uses a resonant half-bridge topology; in a half-bridge circuit, two transistors control power through the transformer first one direction and then the other. Common switching power supplies use a PWM (pulse width modulation) controller, which adjusts the time the input is on. The L6599, on the other hand, adjusts the frequency instead of the pulse width. The two transistors alternate switching on for 50% of the time. As the frequency increases above the resonant frequency, the power drops, so controlling the frequency regulates the output voltage.

[8] The processor in the charger is a MSP430F2003 ultra low power microcontroller with 1kB of flash and just 128 bytes of RAM. It includes a high-precision 16-bit analog to digital converter. More information is here.

The 68000 microprocessor from the original Apple Macintosh and the 430 microcontroller in the charger aren't directly comparable as they have very different designs and instruction sets. But for a rough comparison, the 68000 is a 16/32 bit processor running at 7.8MHz, while the MSP430 is a 16 bit processor running at 16MHz. The Dhrystone benchmark measures 1.4 MIPS (million instructions per second) for the 68000 and much higher performance of 4.6 MIPS for the MSP430. The MSP430 is designed for low power consumption, using about 1% of the power of the 68000.

[9] The 60W Macbook charger uses a custom MSP430 processor, but the 85W charger uses a general-purpose processor that needs to loaded with firmware. The chip is programmed with the Spy-Bi-Wire interface, which is TI's two-wire variant of the standard JTAG interface. After programming, a security fuse inside the chip is blown to prevent anyone from reading or modifying the firmware.

[10] The voltage to the processor is provided by not by a standard voltage regulator, but a LT1460 precision reference, which outputs 3.3 volts with the exceptionally high accuracy of 0.075%. This seems like overkill to me; this chip is the second-most expensive chip in the charger after the SMPS controller, based on Octopart's prices.

[11] The voltage reference chip is unusual, it is a TSM103/A that combines two op amps and a 2.5V reference in a single chip. Semiconductor properties vary widely with temperature, so keeping the voltage stable isn't straightforward. A clever circuit called a bandgap reference cancels out temperature variations; I explain it in detail here.

[12] Since some readers are very interested in grounding, I'll give more details. A 1KΩ ground resistor connects the AC ground pin to the charger's output ground. (With the 2-pin plug, the AC ground pin is not connected.) Four 9.1MΩ resistors connect the internal DC ground to the output ground. Since they cross the isolation boundary, safety is an issue. Their high resistance avoids a shock hazard. In addition, since there are four resistors in series for redundancy, the charger remains safe even if a resistor shorts out somehow. There is also a Y capacitor (680pF, 250V) between the internal ground and output ground; this blue capacitor is on the upper side of the board. A T5A fuse (5 amps) protects the output ground.

[13] The power in watts is simply the volts multiplied by the amps. Increasing the voltage is beneficial because it allows higher wattage; the maximum current is limited by the wire size.

[14] The control circuitry is fairly complex. The output voltage is monitored by an op amp in the TSM103/A chip which compares it with a reference voltage generated by the same chip. This amplifier sends a feedback signal via an optoisolator to the SMPS control chip on the primary side. If the voltage is too high, the feedback signal lowers the voltage and vice versa. That part is normal for a power supply, but ramping the voltage from 16.5 volts to 18.5 volts is where things get complicated.

The output current creates a voltage across the current sense resistors, which have a tiny resistance of 0.005Ω each - they are more like wires than resistors. An op amp in the TSM103/A chip amplifies this voltage. This signal goes to tiny TS321 op amp which starts ramping up when the signal corresponds to 4.1A. This signal goes into the previously-described monitoring circuit, increasing the output voltage.

The current signal also goes into a tiny TS391 comparator, which sends a signal to the primary through another optoisolator to cut the output voltage. This appears to be a protection circuit if the current gets too high. The circuit board has a few spots where zero-ohm resistors (i.e. jumpers) can be installed to change the op amp's amplification. This allows the amplification to be adjusted for accuracy during manufacture.

[15] If you measure the voltage from a Macbook charger, you'll find about six volts instead of the 16.5 volts you'd expect. The reason is the output is deactivated and you're only measuring the voltage through the bypass resistor just below the output transistor.

[16] The laptop pulls the charger output low with a 39.41KΩ resistor to indicate that it is ready for power. An interesting thing is it won't work to pull the output too low - shorting the output to ground doesn't work. This provides a safety feature. Accidental contact with the pins is unlikely to pull the output to the right level, so the charger is unlikely to energize except when properly connected.

[17] The imitation charger uses the Fairchild FAN7602 Green PWM Controller chip, which is more advanced than I expected in a knock-off; I wouldn't have been surprised if it just used a simple transistor oscillator. Another thing to note is the imitation charger uses a single-sided circuit board, while the genuine uses a double-sided circuit board, due to the much more complex circuit.

[18] The burnt charger is an Apple A1222 85W Macbook charger, which is a different model from the A1172 charger in the rest of the teardown. The A1222 is in a slightly smaller, square case and has a totally different design based on the NCP 1203 PWM controller chip. Components in the A1222 charger are packed even more tightly than in the A1172 charger. Based on the burnt-up charger, I think they pushed the density a bit too far.

[19] I looked up many of the charger components on Octopart to see their prices. Apple's prices should be considerably lower. The charger has many tiny resistors, capacitors and transistors; they cost less than a cent each. The larger power semiconductors, capacitors and inductors cost considerably more. I was surprised that the 16-bit MSP430 processor costs only about $0.45. I estimated the price of the custom transformers. The list below shows the main components.

| Component | Cost | |

|---|---|---|

| MSP430F2003 processor | $0.45 | |

| MC33368D PFC chip | $0.50 | |

| L6599 controller chip | $1.62 | |

| LT1460 3.3V reference | $1.46 | |

| TSM103/A reference | $0.16 | |

| 2x P11NM60AFP 11A 600V MOSFET | $2.00 | |

| 3x Vishay optocoupler | $0.48 | |

| 2x 630V 0.47uF film capacitor | $0.88 | |

| 4x 25V 680uF electrolytic capacitor | $0.12 | |

| 420V 82uF electrolytic capacitor | $0.93 | |

| polypropylene X2 capacitor | $0.17 | |

| 3x toroidal inductor | $0.75 | |

| 4A 600V diode bridge | $0.40 | |

| 2x dual common-cathode schottky rectifier 60V, 15A | $0.80 | |

| 20NC603 power MOSFET | $1.57 | |

| transformer | $1.50? | |

| PFC inductor | $1.50? |

[20] The article Breaking down the full $650 cost of the iPhone 5 describes Apple's profit margins in detail, estimating 45% profit margin on the iPhone. Some people have suggested that Apple's research and development expenses explain the high cost of their chargers, but the math shows R&D costs must be negligible. The book Practical Switching Power Supply Design estimates 9 worker-months to design and perfect a switching power supply, so perhaps $200,000 of engineering cost. More than 20 million Macbooks are sold per year, so the R&D cost per charger would be one cent. Even assuming the Macbook charger requires ten times the development of a standard power supply only increases the cost to 10 cents.

70 comments:

I bought one of the original Compaq luggables, must have been about 30 years ago. Not paying attention to the documentation, I had a card containing a Z80 and memory for running CPM software. Compaq published a list of acceptable add-in cards, my CPM card was not on the list. The Compaq power supply went belly up, and I discovered that Compaq wanted about $350 for a replacement, which wasn't standard off-the-shelf. This was ~1985 dollars, a lot more today.

I reverse engineered the Compaq power supply, the entire 5 volt system (which powered all of the chips at the time) was supplied by a single 7805 regulator without any additional heat sink. I wasn't going to waste effort repairing the supply, much less waste a ton of money replacing the supply with another terribly designed unit, so I cut off all the mother board power supply connectors and wired in a replacement using a standard PC power supply.

My computer worked for several more years, but wasn't portable at all. I never bought another Compaq.

Switched mode power supplies ought to run on DC input, if the input voltage is sufficiently high (100VDC or so?). Have you ever tried it? The DC goes right through the bridge rectifier, the PFC should ignore it, and the chopper will accept it. Old radios based on vacuum tubes sometimes used a similar trick; they would operate on a wide range of AC or DC power:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AC/DC_receiver_design

@JL If the controller is looking for a zero crossing, like most PFC controllers, it may not work with DC.

Great posting. Thanks very much.

The LT1460 might be there to lower the noise getting into MSP430F2003 16bit ΔΣ ADC.

There will be obviously switching noise from the MCU itself but that is smaller issue at was probably taken into account by the chip designers. Powering small MCU's that do ADC conversions directly from the voltage references is quite popular. Voltage references can't normally provide high currents to power bigger devices but this one is very low power.

Very interesting!

As for Apples cable I really don't know what in the hell is wrong with them. The consistently use cables that don't hold up to even mild handling. As much as I like my Apple products, I do have a few, I'm not at all pleased with the cables they supply.

Now the interesting question; how dos the third party charger deal with the product verification cycle?

Technically , have anyone can give me advice that we should keep charger plug-in when using macbook or plug-out when full-charge?

the cord is the weak spot .. they ALL fray, and require the purchase of a new block, and the original heads to the landfill ..

for want of a nail …

crap design on the cord, have to admit

> As for Apples cable I really don't know what in the hell is wrong with them.

It has been suggested, though I've seen arguments for and against, that since Apple stopped using PVC in their cables for environmental reasons the cables are more prone to fraying.

I am not an electronics or electrical engineer to understand this thing completely, but as per my basic electrical knowledge which I learned in 12th grade physics, there are a few doubts:

"The primary chops up the high-voltage DC from the PFC circuit"

"It takes the high voltage DC from the PFC circuit, chops it up and feeds it into the transformer"

I have never heard of a transformer that works in DC because transformers work by the principle of induction right, and induction cannot transfer energy to the secondary coil from primary unless there's change of flux in primary.

Power factor correction is also a term that's related to AC, never heard it being used in DC.

Please clarify my doubts :)

Some old components in there - the MSP430 is date-coded Feb 2006, and the SMPS chip looks like wk 13 2009.

Nilesh,

The chopping of the DC converts it to AC, though a lot closer to a square wave than a sine wave. That gives you the change of flux that makes the transformer work. The Wikipedia article at https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chopper_(electronics) may be instructive here.

PFC has to do with the load presented to the power line by the charger: whether the voltage leads or lags the current. This is pure AC, with no DC involved. Wikipedia again is useful: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_factor , with special attention to the section on switched-moore power supplies.

I hope this helps.

w5ego, thanks!

Hi Ken,

Very good teardown! I work as engineer and use the same L6599 CI, What suprise for me that Apple use the same.

The cost of a LLC transformer is about $1,50 and the PFC inductor is $1,25.

Thanks

Great article. Does the unbranded charger provide a good value? Does it do the job? Will it harm my Mac?

Great article! Thank you very much.

Now I know why my MacBook Air actually has ruined power connector. I was using a cheap power supply after the original Apple one broke. After a while I realized that the MBA would not charge anymore and checked the socket on the MBA. I noticed that it had black burn marks and also partially melted plastic. I assume those stem from sparks and arcs during plugging and unplugging of the non-apple power adapter. That probably didn't had the safety feature to only turn on power if the connection is firmly established.

38 years and counting of copying what's already successful and telling the world that it's revolutionary and they invented it.

Very interesting! Perhaps you or someone reading can help with my problem with the Apple charger ... it just falls out of the socket. Does anyone else have this problem or know of a solution? Here's a short video I tweeted to @tim_cook but no reply yet.

https://twitter.com/MattDowle/status/670424914487193601

Great teardown! I'm curious if someone with a real EE background could explain why the voltage is different and has to be negotiated between the 65W and the 80W-powered laptops. My reading of the specification of the MacBook/MBPro is that they accept a range of different voltages. Wouldn't it make sense to just standardize on one voltage (e.g. 18v)?

I've been powering my MBP from a hobby 4s LiPo battery and it seems to work fine. Still can't find what the highest input voltage is for the MBP which is quite an annoyance. Some sites say 22v, others 25v.

The cable frays because (sigh) of two factors:

1) The outer conductor is aluminum, which work hardens and gets brittle over time, especially when the outer insulation layer gets stiffer. I think this is why the newer cables are even more problematic than the older ones.

2) People aren't very good about not pulling on their cables and wrapping them tightly around corners. This is a particular problem right at the connection points on both ends.

Bottom line: Apple would be well served to move away from the 'pretty' round coax able design and move to a flat design with more and thinner conductors, so that the strain between the outer side and inner side was reduced when going around sharper corners. Adding cable connectors so that the cable is replaceable, not just the whole charger, would also help.

Ditto an earlier comment - I read a little further after claiming to feed DC voltage to a transformer and then stopped. Perhaps the author is lazy about terminology and there is a DC-to-DC converter rather than a transformer or that the DC isn't really DC but a chopped sine wave, but either way as written I have zero trust other liberties weren't taken with the 'explanation'. Will find a better teardown somewhere else.

"[16] The laptop pulls the charger output low with a 39.41KΩ resistor to indicate that it is ready for power."

So, if I put 39.41KΩ resistor as a load can I get some amps out from this charger to my laptop? (If I leave magsafe connector in cable and get voltage out from cable with different connector)?

Article mentions that 39.41KΩ resistor should be correct to get charger active ? Has anyone try this ?

Jeremy: I believe the issue with the voltage negotiation is backwards compatibility for old Macbooks are expecting the lower voltage. Apple wanted to move to higher voltages but older laptops weren't designed for it. The negotiation lets the power supply handle both types. Apple gave up on supporting older Macbooks with the Magsafe 2 connector. This is why you can get an adapter to use an old charger with a Magsafe 2 laptop, but not vice versa.

DC Anonymous: you're missing the point of a resonant converter. Switching power supplies normally chop up the DC into pulses, which are fed into the transformer. (Obviously steady DC won't work in a transformer.) The resonant controller is a bit more advanced, using a half-bridge configuration to send out-of-phase DC pulses. With the resonant converter, these pulses resonate in the LLC circuit and approximate a sine wave, allowing better switching.

I refer you to the L6599 datasheet for details.

39.41K Anonymous: yes, if you put a 39.41K resistor as load for one second, you can get power out of your charger. The tricky part is you can only get about 5mW through such a large resistance (which is by design). If you want to get a practical current, you need to swap in a lower resistance when the voltage jumps up. This does work - I can do it by hand about 1/3 of the time. If you don't get the timing right, the power supply will shut back down and you need to try again. Putting an oscilloscope across the output will make it clearer what is happening. The resistance doesn't need to be exactly 39.41K; a 10% resistor works fine for me.

@JL and the replying anon:

Indeed, the MC33368 shouldn't do anything when the charger is fed with DC -- it does look for a zero-cross to start boosting the voltage, and is also powered partially from a winding on the PFC inductor. However, this simply means that the unboosted DC input goes straight to the resonant converter minus the boost diode's drop, as the switch in a boost converter is in parallel with the load.

Hello! Thank you for this post! I know that it is widespread problem od such devices. i want ot get your consultation. Please, tell me: if I want to plug in this model http://hardware.nl/power-supply/dell/k2583.html, is it possoble to make with macbook? I afraid to try to do it without any consultations. I will be very thankful for your answer!

Nice article! Came here looking for a way to find the cause of failure of my 85W apple power adaptor (A1424). The DC output voltage is only 1mv. There seem to be no other obvious problems with the unit (caps look ok visually, no burn marks/smell etc.)..Would appreciate some tips..

Hi,

Do you happen to have a photo of the backside of the small microcontroller board? I have a non-working charger I'm trying to fix but it's proving quite difficult. The cable went bad (on both sides!) but after replacing it, the initial voltage appears to be only 2.1V instead of 3.3V. I do have some 3.3V signals somewhere so I assume the regulator is still OK but I'm trying to figure out where the 2.1V comes from. Apparently the shorted cable destroyed something :-(

Getting the board out appears quite tricky so I was wondering if I can piece together a simple schematic/pinout from your photos. Thanks!

Best regards,

Jasper

The two metal shields with perforations are likely for EMI reduction. Only the thicker shield without perforation is a heat sink.

@ Jeremy Gilbert

Using a hobby LiPo is a pretty bad idea as if you get the voltage too low then the pack is dead and they need specialist LiPo charging. You are really taking a serious risk not using a dedicated LiPo charger.

For the higher wattage, either the voltage or the current needs to increase (Ohms Law) to get the higher watts.

Increasing the current would increase the resistance (and heat) in such thin cables so increasing the voltage is a sensible solution.

I am done with apple products. They are absolutely demonstrably built to fail and I'm tired of being forced to buy a whole new device anytime something goes wrong. And I'm not the only one... people are giving up in droves http://helpmebro.com/posts/R1RFHCeAx5

Would like to see a similar tear down and analysis of a high quality desktop PSU, like an EVGA gold rated 800 watt psu or similar.

No wonder they go wrong so often-- talk about over-engineering.

I worked in Europe for a well known lighting company, and for a while I was involved in the compact fluorescent lamps: these have power rectification circuitry from mains voltage, which may be used in circumstances of high temperature, since the lamps may be enclosed in and "upside down" installations. Gets hot. These circuits are called drivers. Apart from safety features, a good one does clever things like prewarming the cathode before the lamp turns on, to help it last many more switching cycles, and of course it has to avoid polluting the power supply since in some applications there are many of them on the same phase. But that costs money. When our first efforts to source circuits from China began, many suppliers were visited. One of them had a great cost saving method: take the driver from a traditional supplier's lamp, and one by one remove components until the driver failed.

Nice teardown. I am in the process of assembling & building my own very clean (quality/filtered) power supply for my mobile requirements (going direct DC to DC) and was thinking a pure 20v was all that was needed. Go figure this is a little more complicated.

The board & chip I'll be using is really efficient (expected 95%-99% always) and so should not waste power when the current draw is low (say when my 15" MBP is fully charged), but that also assumes the MBP won't waste the 20v provided and just draw more current because it can?

Does anyone have the answer to that? Should it really drop the voltage some so logic in the MBP does not waste power?

Ken, the separation between high and low power sections is not detailed enough here for me to know the answer, but in your hands on experience with dissecting this or any apple charger and based of your one comment above, do you think it possible to cleanly add a tap into the low power portion (bypass the transformer process) and supply a base/clean DC voltage to the board?

My hope is to repurpose my latest or perhaps an older 85w charger and to replicate exactly what apple does by using all their logic after the basic AD-DC transformer stage, and not just the connector. Has anyone you know of done this?

Just tore apart a charger that died shortly after purchase. Does this look counterfeit? Might be hard to tell because they glopped glue all over and inbetween the internals.

http://i.imgur.com/PV07kk0.jpg

http://i.imgur.com/tFdJ4qk.jpg

http://i.imgur.com/r3qnDqj.jpg

asdf: the charger in your photograph looks counterfeit. The genuine Apple chargers have many, many more components; compare with your third photo.

"That switching power supply was as revolutionary as the Apple II logic board was. Rod doesn't get a lot of credit for this in the history books but he should. Every computer now uses switching power supplies, and they all rip off Rod Holt's design." --Steve Jobs

Why do you say Steve Jobs' quote about Ron Holt is "entirely false"?

The only part about that quote that may (may!) be less than true is the last part: "they all rip off Rod Holt's design."

I'm very disappointed with macbook charger (magsafe 2 60W). I bought it with the macbook more than 2 years ago and last month my daughter accidentally dropped the charger on the floor. since then I can use the charger anymore because it always cause the wall main power turned down/tripped. it seems the charger shorted. At first I suspect there was something wrong with the cable output from the charger to macbook port. I tried to disassemble it and remove the cable from the charger board. then plug in the charger to the main power but it still make the main power turned down. now i think the problem is on the charger board but not sure about the components on the board.

Poor high-voltage insulation. Completelly defeated by the row of those resistors on the bottom of the board photograh. Plus, that black "insulation sponge" or what ever it is called, is glued directly on the insulation gap, which can cause tracking. GJ Apple...

Would it be possible to get a apple Mac book pro 2015 running off 12 volts?

I'm living in a Sprinter van. Given the

Would it be possible after opening up the mains charger to inject a D.C voltage say using a variable voltage doubler to provide the 16.5 or 18volts?

I have a pure sinewave inverter but i think it is probably more efficient to use 12volts directly if possible.

Good day,sir~

Could I ask two questions about MSP430 here? Please forgive me if it's not suitable.

I am coding an MSP430 ( the MSP430AFE221IPW datasheet )using the code composer, but I can't understand that:

1.What specific assembly language does it use?(I am looking for a guide to learn the syntax but cannot find the name of the language.)

2.What is a list of addressable components on an embedded system called? I see them address components and im not sure where the names come from.)

Thank you in advance!

Hi Agd Fadjd. The MSP430 uses its own assembly language (i.e. it's just called MSP430 assembly language) The MSP430 User's Guide explains the instruction set in detail. The MSP430 Assembly Language Tools manual goes into details on the syntax. The manual for your specific chip should describe the available peripherals and their addresses. Texas Instruments has a MSP430 forum, which would be a good place for additional questions.

Hello,

is it possibile to use MagSafe with a UPS with an approximate sine wave output (NOT a pure sine wave) ? Any problem to the mac with this combination ?

Thanks

Alberto

Hi Ken thanks for sharing your work. With A1222 You confirmed with (15) that indeed it shows only 6V when tested with multimeter. You saved me from having to open the big shell. My problem exists in the Mag safe connector end.

Does anyone know what is the value of fusible resistor (next to big cap) as seen on the post image?

Mine is blown and I can only read:

0.1 _ Ω

1 WJ

FU __ N

* where _ represent unreadable characters.

Thanks,

Gregor

Does anyone know what is the value of fusible resistor (next to big cap) as seen on the post image?

Mine is blown and I can only read:

0.1 _ Ω

1 WJ

FU __ N

* where _ represent unreadable characters.

Thanks,

Gregor

I wish I had read your article before I tore apart my Magsafe II charger, trying to find what's wrong with it, as my voltmeter measured 0.0 to 0.6V output voltage! Nothing was wrong with it, actually. It was not activated due to lack of proper load.

However, your fantastic study details inspired me to find a dual solution, which will also answer many other readers' questions, namely:

a. Fully activate my magsafe-2 charger (60W, 16.5V) for ALL alternative uses wished, regardless of its internal temperamental "brain",

and,

b. Convert the charger to magsafe-1 for use with older MacBooks

Details (and possibly pictures) on a following comment, after finishing my tests (I am currently writing this on a MacBook pro 2010 using this "hacked" magsafe charger).

Stratis Georgiou, Athens, Greece

Hmm, is there anyone out there who repairs the damaged cord on a MacBook charger, maybe with something more sturdy?

Thanks for the excellent article! I was surprised to see how complex is the circuitry of the Apple charger.

@Stratis Georgiou: I would love to see your solution, esp. the full activation part. Are you going to share this here?

Thank you for this helpful article!

Later versions (marked A1343) have a 16 pin SMPS chip marked DAP019 - and give less than 1V output with no load - not 3V or 6V as for some other models. (If you connect a 39k resistor to the output and wait a second, you get the full 16V output voltage.)

There is no output DC between the white and the black wires on the board. I couldn't see any damage on the components. What could be failing?

I measure 120V AC input, but nothing on output.

Yes I do it and it’s quite simple to do it your own. Here is how https://youtu.be/KzUon3HaJuM

Here is how I do it https://youtu.be/KzUon3HaJuM

Sometimes if dropped the older macbook chargers would suffer a shock which could break one of the legs of a coil, you could re-connect a new leg to the coil and it worked again.

The comment on the low voltage on the output of the magsafe adapters was priceless!

I thought my chargers were dead and would need caps or optocoupler changing but i simply fitted the new cables and they work fine.

Note. Some of the cables on ebay are not as good as others. I bought some of the rectangular ones and some of the cylindrical ones and the rectangular ones had better quality cable and insulation around the negative plus it had the correct strain relief grommet, the other had no grommet.

"45% profit margin on the iPhone": doesn't include vendor licenses and marketing; does it?

How do you know the voltage is 16.5 if the probe says 6?

How efficient are these power adapters under different loads compared to the imitations?

Can I connect a dc power supply to the neg. and pos. leads on the Mac Book Pro 2011 and charge the laptop with a 16-18 volt battery?

I see that using original MagSafe is a better option rather than buying a Chinese knockoff. But is it the same case with th enew USB-C chargers that apple ships its laptop with?

Please reply. Thanks. My MacBook Pro 13 USB-C adapter just fried and i was thinking of buying an Anker charger instead.

Thanks for a great teardown on the Magsafe.

I had to open a 45W version with a frayed output cable.

The complexity is very impressive.

The reason I was searching for information was to find out about the grommet.

I would really like to know what material it is, as I have never seen such a tough grommet.

Extremely hard to separate from the plastic bit through which the output leads pass.

It seems like the plastic has been molded around the outlet cable.

is it possible to use a battery charger for pc on a macbook?

obviously replacing the cable

Assuming the voltage and amperage are in to the specs, yes. In this way you need to be carefull because full current will flow as soon as you connect the magsafe adapter to the charging port. If something goes wrong you risk to apply full voltage on the adapter_sense rail as example and get serioulsy in trouble... Cheap chinese adapters does almost the same that's why I suggest to stick with the original one when possible. Most of the time never brakes; instead of changing the cable to a pc adapter, better to replace the broken apple one. Not a difficult task as repairing the one-wire circuit on a logic board if you was so lucky not to have fried the entire board.

I wonder if purchasing a used genuine apple charger is a good choice. E.g. with a rationale that (if the cables are ok) it will have less probability of failing due to internal reasons since it has been successfully working for quite a while and didn't fail.

Can you please share the similar teardown for Macbook Pro adapter?? With components' size

Hi, I have an 85W MagSafe Power Adapter, Model No: A1343, worked ok,

then suddenly dead. Opened it up and there are a few components blown.

Two resistors and a chip.

You can see more on pictures here:

https://ibb.co/7KHGDWw

https://ibb.co/VmbJptk

https://ibb.co/0tqBk1t

https://ibb.co/mBTSrKY

https://ibb.co/gmfrCcH

https://ibb.co/kXtLG2M

Unfortunately I can only read the few last characters on the chip - an N on the top and 3261 or 5261 on the bottom (can't rally tell, the character is halfway visible but most probably is a 5261). The chip is blown right on the position where the model/type is printed. The resistors are also hard to tell.

Can anyone of you experts tell me if it is possible to source the right chip and the resistors and replace them? All other seems ok. Another question is why this happened?

Will it hipoteticaly work if those things are changed or is there a problem somewhere also and they will be blown up again?

Thank you for your help!

Hi, I just opened this article to see whats in a brick cause mine stopped working and started thinking what actually is inside the charger.

I am a second year undergrad studying electrical engineering, and my first year had just ended. I took my first electrical class in college just last semester and saw a lot of the things we had just studied in the charger. It made me feel good and excited for what I am studying in college.

I had started to feel a little frustrated and angry at the college, especially after the grades, but thanks to you, I felt better and got reminded why in the first place I took engineering. Thank you for making me realise whats important in life and college and remind me that I'm not here for grades but to actually learn stuff.

Thank You :)

While I am impressed at the sophistication of what's inside that Mac charger, the complexity + failure rate make it a terrible product for a consumer. Frankly, I'd be far happier with a totally old-school linear regulated DC power supply set at 16v (or 18, or whatever the Macbook requires). Sure, it would be a clumsier, heavier "brick", and get warmer, but so what? With a solid cord on it, it would last forever.

Great article, really good read!

I have a charger that seems to be on the way out, though there's not much wrong with it.

All that's wrong is the connection. If I angle it a little - ie, push down on the back - it seems to work, though not always.

The two power pins have discoloured, gone a deep bronze. I imagine that's something to do with it.

Any ideas?

Many thanks.

First, to the author, thanks for an awesome teardown article. Hopefully reading Unknown reply on 13 Jul 2022 makes it all worthwhile.

@typer: I have the same issue. My MBP is pretty old and I have trouble charging it now. I think the problem is with the DC-IN connector on the MBP, replacements are pretty cheap on Amazon, e.g.:

https://www.amazon.com/Odyson-DC-Replacement-MacBook-Unibody/dp/B07FPSFFQ2

so have I ordered one, hopefully will fix the problem.

nice blog, thank

Post a Comment